Lauren Elkin begins her book about bodily art with a charming ode to the punctuation mark that she in American English calls a ‘slash’ and we in British English call a ‘stroke’. She likes the way it expresses ‘division yet relation’. Brings disparate things together. Makes space for ambiguity. Blends and blurs. And/or. She writes:

The slash is the first person tipped over: the first person joining me to the person beside me, or me to you. Across the slash we can find each other. Across the slash I think we can do some work.

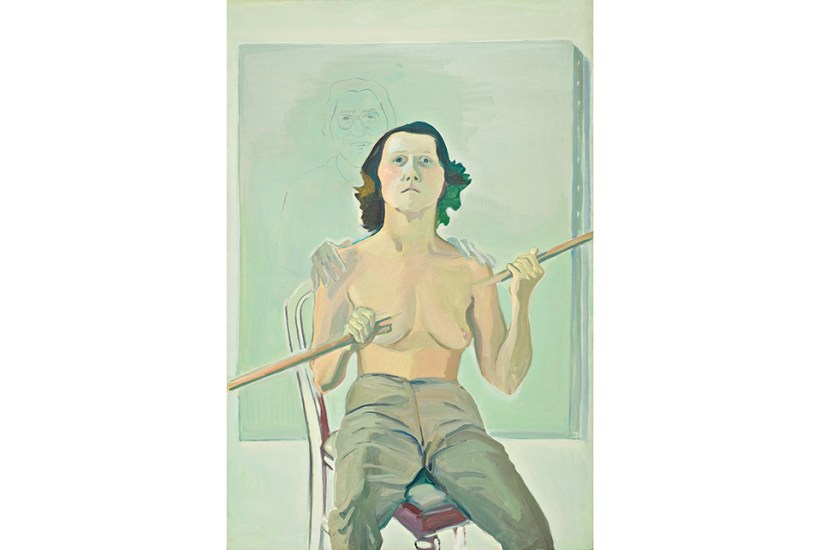

That work begins in Art Monsters with a lively and vibrant account of feminist art that articulates the everyday experience of having a body. This might not sound especially radical but, as Elkin writes, the female nude is ‘art or obscene, depending on the context’. She continues: ‘Made by man, in the context of the history of art, it is beauty itself.’ Made by a woman, it can be inappropriate, vain and scandalous.

The book borrows its title from two much-quoted sentences from Dept. of Speculation (2014), Jenny Offill’s fragmentary novel about modern marriage: ‘My plan was to never get married. I was going to be an art monster instead.’ The expression ‘art monster’ has now become popular in the feminist lexicon, writes Elkin, sparking conversations about what it means to have a family and make art. But rather than focus on female artists’ lives, she encourages us to look at their work – ‘at what it was that they were so bent on doing that they ran the risk of being called a monster’.

Which is what this book does brilliantly: engage with the physicality of art, the sensory, texture, lumps and all. It juxtaposes artists and writers who insist on both beauty and excess, take joy in flesh and ‘dare to overwhelm the limits assigned to us’. Virginia Woolf, in her 1926 essay ‘On Being Ill’, considered the problem of writing ‘the daily drama of the body’. In 1975, Carolee Schneemann stood on a table in a gallery in East Hampton, New York, pulled a roll of paper from her vagina and read aloud from it to give the female body a voice. Kara Walker’s silhouettes defy ‘the rules about what kinds of images (black) women can make’. Lee Miller’s meaty mastectomy portrait of twinned breasts served on plates is a queasy rejection of the male gaze.

A writer and translator, Elkin pays close attention to language. She realises the word ‘monster’ is just as effective as a verb, and that in this form it tells us what art does:

It makes the familiar strange, wakes us from our habits, enables us to envision other ways of being and lets the body and the imagination speak and dream outside the strict boundaries placed on them by society, patriarchy, internalised misogyny.

Outside, but not against. Rather than ‘a channelling of normative practice’ or ‘a rebuttal of it’, art that monsters is ‘a deviation, a hard left into a new territory’.

The book is packed with theory, but is jargon-free. As well as critical, Elkin’s prose is chatty and at times enjoyably blunt:

It has been a major contribution of feminist artists… that the notion of the work of art as autonomous and apart from the world of politics, as possessed of objective aesthetic qualities, is a load of horseshit.

The stroke, or slash, appears throughout, not just as a mark but in the multiplicity of monstrous art and, indeed, feminism. Elkin is intrigued by ‘the way certain conflicts can make the broad church of feminism feel like a single pew in which we’re all jostling for a seat’. She prizes open the fissures that emerged in the 1970s when feminist artists who were depicting their own bodies or those of other women were reproached for playing into male fantasies. The trouble, she says, is that walling off the female body makes it ‘invisible’.

This is the antithesis of what monstrous art does best – which ‘goes closer, gets touchy, tacky, ucky’. Through Elkin’s vivid visual analysis we feel as well as see. Genieve Figgis’s ‘Blue Eyeliner’ (2020) has a ‘wobbly blobbiness all of its own’. Eva Hesse’s ‘Right After’ (1969) is a ‘cobwebby fibreglass cord thing’. Elkin isn’t afraid of feeling. On the contrary: ‘The art that most beguiles and intrigues me is gunning for our sentiments.’ Art that’s visceral and honest and unwieldy.

Exactly the kind of art we need now, she argues. She wrote Art Monsters in the years following Donald Trump’s election, #MeToo, Harvey Weinstein, Black Lives Matter and Covid-19. It seemed crucial to find a way to ‘cure our self-repulsion’ and consider ‘how to be in a female body in the early 21st century’; to look back to a tradition of women struggling with ‘the beauty myth, bodily autonomy, reproductive rights’ to feel less alone; to make room for complex feelings.

Complex. Changeable. Out of bounds. Ambiguous, like the stroke. Monstrous art, Elkin writes, is weird and bold. ‘What makes it good – what sets it apart – is its commitment to a sometimes scathing honesty.’ You could say the same for this superb book.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in