Published in German in 2011, this book was the high point of a 20-year-old tradition of ‘Anti-Gypsyism Studies’, which suggested that all previous histories of Roma by non-Roma represented a self-serving, defensive ideology of oppressors demonising the oppressed. Anti-racist scholars should therefore stand aside from such colonialist impertinence and leave the actual history of Roma to be written one day by Roma themselves. They should concentrate on chronicling the racism of their own people – Europeans, and especially the Germans.

The book is not, therefore, a history of Roma, and was not intended as such. The original title was Europa erfindet die Zigeuner, which means ‘Europe invents the Roma’. It is a little disingenuous of the publisher to market it as general history. It has no reference to Ottoman, Armenian or Byzantine literature. The story begins when western Europeans started making up stories about mysterious, threatening oriental aliens in about 1450, and ends with the failure of the story of the Holocaust to dethrone this racism in the way anti-Semitism was discredited.

This story, of misguided fiction or historiography about Roma, Gypsies and Travellers from the past 600 years, especially in German, is very well-referenced. Klaus-Michael Bogdal summarises many tedious books, one after another. He has read them, so that we don’t have to. ‘Anti-Gypsyism studies,’ he tells us, stem from a radically relativistic critique made by the Dutch historians Leo Lucassen and Wim Willems in the 1980s of conventional histories of Roma. They held that all historical narratives are back-projections of the present world view of the narrators, and so are ideological constructions, reflecting their socio-economic interests. They argued that the concept of ‘Gypsies’ was invented in 1783 by an ‘Enlightenment’-style policy wonk named Heinrich Grellmann, who, like policy wonks down the ages, sought advancement by speaking comforting fictions to power. He justified the switch from marginalisation to assimilation, already adopted as a policy by enlightened rulers such as the Empress Maria Theresa of Austria from 1756 onwards.

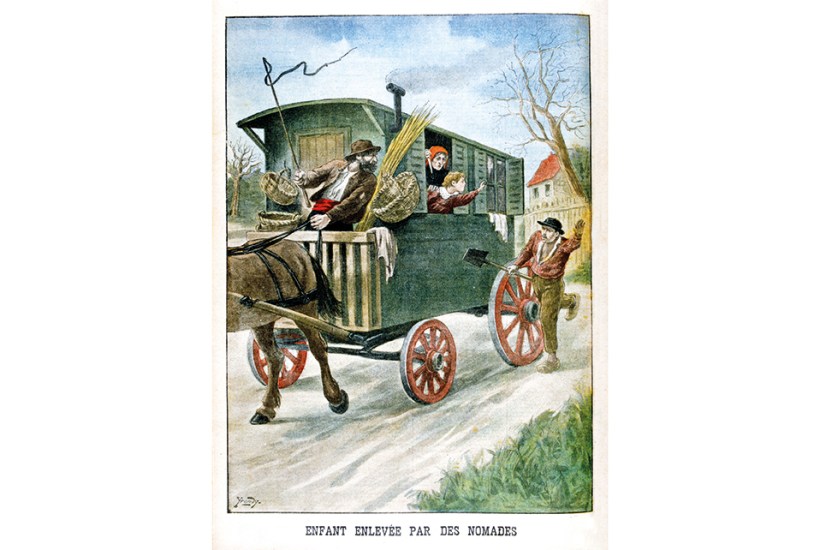

Bogdal suggests that Grellmann did not invent the Gypsies by himself but was part of a self-perpetuating cultural tradition of invention since the 15th century. Grellmann’s innovation was his ‘discovery’ that Romani is a Prakritic language, which for him proved that very varied groups of Gypsies, Travellers and Roma in Europe were a ‘race’ from India. If they did not speak Romani, then there must have been inter-breeding. Their inherent racial characteristics were the explanation of their vagrancy, nomadism, criminality and occasional cannibalism. For scientific racism in the 19th century, ‘Gypsies’ were the exception that proved the rule. They had been present since 1400 in the civilising climate of central and western Europe, and yet they were still uncivilised primitives!

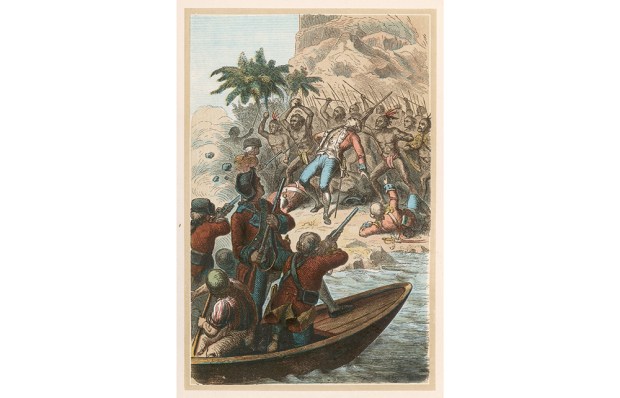

So, just as in European colonies, the white man had a civilising mission. Grellmann was translated into major European languages (twice into English, 20 years apart – how many recent German social science texts can demonstrate such influence?). When assimilation failed, what policy was left but the final one of genocide?

Like all Anti-Gypsyism Studies, Bogdal pays tribute to Michel Foucault; but his method is quite the opposite. Foucault is the consummate contrarian, identifying discourses, which he conceives of as policemen in our heads constraining our thoughts but which can be defeated by irresistibly plausible evidence gleaned from pains-taking archival research. ‘Foucauldian theory’ is thus a kind of contradiction in terms: the man never found a theory which he did not want to skewer with some scalpel-like counterfactual. Far from identifying a discourse which needs discrediting, Bogdal sets up the ideology of Anti-Gypsyism as an obviously deluded psychological defence mechanism into whose framework he crams all the texts he examines. He fails to recognise that by ignoring the agency of Roma themselves he colludes with the very objectification that he deplores.

This neglect of actual history leaves Bogdal with a cavalier approach to checkable facts, and a promiscuously mixed approach to primary and secondary sources. He follows Willems’s misreading of George Borrow, entirely missing Borrow’s irony, and expands it by listing Borrow as one of the founders of the Gypsy Lore Society. In fact Borrow died in 1881, and the Gypsy Lore Society was founded in 1888, and at first defined its own scholarship against what it saw as Borrow’s unreliable romanticism.

Bogdal claims that European literature hasn’t produced ‘a single novel or play that presented either the history of Romani people or their present-day way of life’. How he can make this generalisation if he is not engaging in actual Roma history is unclear. Elsewhere, contradicting himself, he praises the Roma novelists Menyhert Lakatos and Matéo Maximoff for their realism – though he concentrates on their folklore rather than their politics or discussion of the Holocaust. That this inconsistent and unreliable book won such critical acclaim in Germany, and the Leipzig Book Prize for European Understanding in 2013, is evidence that mainstream European scholarship has yet to do its homework on Roma history.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in