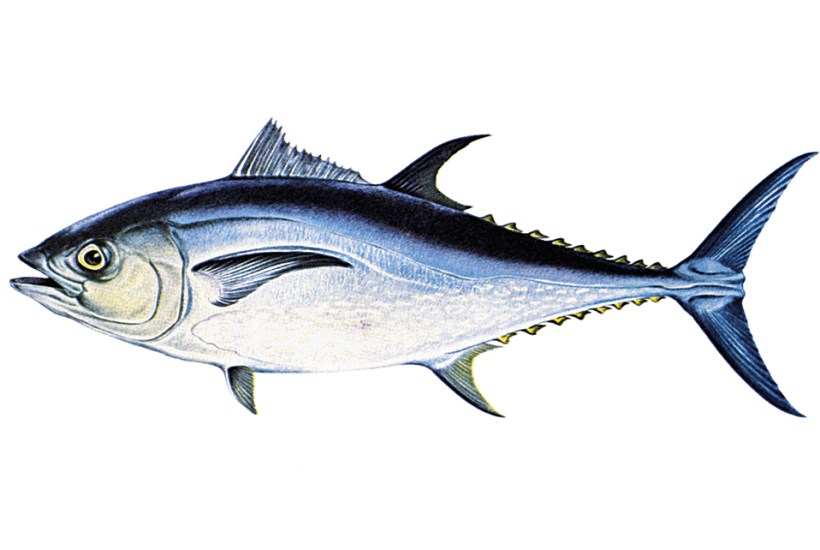

Streamlined, musclebound, warm-blooded and with fins that retract into body slots like a switchblade so it can attain swimming speeds of more than 40 mph, the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna is a wonder of the marine world – the Clan Chief of the Scombridae, that can weigh up to 1,500 lb. It has long been prized by sport fishermen, from Charlie Chaplin to the dentist-turned-bestseller Zane Grey, and there is nothing tentative about a tunny strike. In 1927, after a four-hour battle with one eight-foot giant, Grey wrote: ‘If it were possible for a man to fall in love with a fish, that was what happened to me. I hung over him, spellbound and incredulous.’

Alas for the ABT (as they are known in the trade), they taste so good that they have been hunted for millennia. Their flesh contains a chemical which, on death, is converted into a monophosphate closely associated with umami. Their numbers are now in decline and some think the global population is endangered.

As the Canadian journalist Karen Pinchin describes in her thoughtful, well-intentioned book, it is simplistic to ascribe this crisis solely to the Japanese obsession with sushi and its attendant near-fetishistic rituals. That is a relatively modern vogue which has gone global. In 2019, one Tokyo restaurateur bid US$3 million for a single flash-frozen bluefin carcass. But within living memory this rich, meaty flesh (‘red gold’) was regarded as no better than cat food. In Kings of Their Ocean Pinchin traces the scientific developments that suggest how stocks of this magnificent fish may be managed for the future.

Her basic structure might be called a ‘Convergence of the Twain’. One central figure is Al Anderson, a temperamental Rhode Island charter skipper who was a pioneer of tagging tuna and releasing them – a method which today, with microchip technology (‘fish and chips’) can yield much valuable information about their previously mysterious migratory movements. Captain Al is a maverick, and ornery even by the standards of his profession, though it transpires he is suffering from alcoholism and a brain tumour. In 2004 his boat catches and tags a juvenile ABT, subsequently nicknamed Amelia (after the aviator Amelia Earhart, who happened to have been a tuna aficionado). A scientist captures Amelia again three years later, retags her and finally – spoiler alert – she is netted and killed off Portugal in 2018 and her lifeway is recorded for posterity. In death she even merits her own scientific website.

It was once thought tuna had two distinct Atlantic populations (east and west), but recent research confirms that these remarkable fish often cross the ocean and commingle. This makes international regulation very complex, and Pinchin’s book is partly a chronicle of quotas, bureaucratic infighting, vested interests and the lucrative black market. It’s quite a tale, though much of it has been told before – for instance by the ecologist Carl Safina, whose Song for the Blue Ocean offers a crisper narrative, or by Mark Kurlansky, in whose tradition Pinchin appears to be writing, though her prose is sometimes lacklustre by comparison. Still, you have to applaud an author who is so dedicated that she home-makes garum (that noisome decoction of fish essence, once beloved by the Romans) and who describes how the notorious Korean preacher Sun Myung Moon ran a fleet of tuna boats in the 1970s. ‘You just keep trying until you catch one. That’s the way it goes,’ was apparently his incontrovertible mantra.

To be fair, there are some eye-catching set pieces along the way. One concerns the brief history of Outer Baldonia. Beginning in the 1930s, trophy anglers (including Babe Ruth and FDR) were seasonally attracted to the sleepy settlement of Wedgeport, Nova Scotia to fish for the then prodigious runs of huge tuna and to compete in tournaments. In 1948 one enthusiast, Russell Arundel, purchased a small island there and playfully declared it an independent microstate (Baldonia), dedicated to big-game fishermen and with its own currency, the tunar. The Soviet authorities took a dim view. Eventually, though, the concentration of fish dissipated and Wedgeport slipped back out of the limelight.

Pinchin makes a colourful visit to Spain, where bluefin is still big business. Since Phoenician times, tuna on their spawning run have swum through the Straits of Gibraltar and been intercepted with elaborate netting systems. In Andalusian Arabic, this is the almadraba (or ‘place to hit and fight’), and even now the ritual harvest maintains its own family traditions and is occasionally a tourist attraction. To preserve the quality of fish flesh, today’s fastidious Japanese dealers have replaced with more surgical practices the historic bloodbath of clubbing – once described as ‘like watching a thoroughbred racehorse being hacked to death with an axe’.

Strangely, Pinchin makes no mention of our own history of angling for ABT (a British Tunny Club was founded in Scarborough in 1933) and pays scant attention to ‘ranching’ (the fattening up of juvenile tuna kept in pens). But until someone finds a way of breeding Thunnus thynnus in captivity, I think we are just going to have to eat far fewer of these spellbinding creatures.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in