It is the stuff of nightmares, or a queasily dystopian film plot. A woman is undergoing a surgical procedure in a top-rated US clinic. The aim is ‘egg retrieval’, a process which collects eggs from the ovaries for use in IVF. It involves nerves and hope, long needles and pain – except the patient has been promised that the latter will be minimal, thanks to an injection of fentanyl, a powerful opioid.

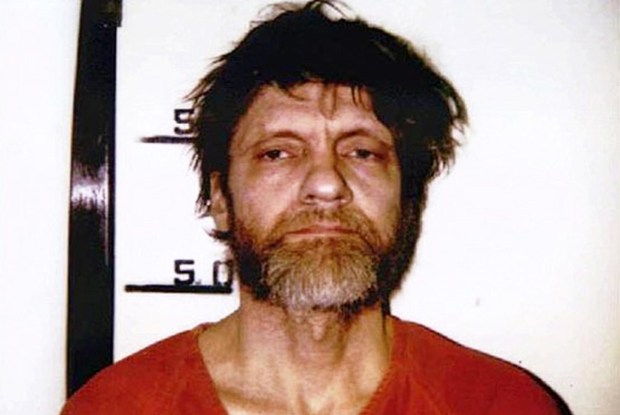

The pain certainly isn’t minimal, however. It’s excruciating. When the woman says how much it hurts, the nurse tops up the dose, and then says the patient has now received the maximum allowed. There might be a touch of reproof in the refusal, if you’re sensitive to such things, and most women are. The woman grits her teeth and carries on with the agonising treatment, telling herself that perhaps it’s her fault, maybe her body is resistant to fentanyl. Except it later turns out that she never received any painkiller at all. A drug-addicted nurse, Donna, has been stealing the fentanyl, replacing it with saline, and no one else at the clinic has noticed.

This is the story explored in the podcast Retrievals, and it didn’t happen to just one woman at the Yale fertility clinic in Connecticut, but as many as 200. Astonishing, you might think, that with so many women reporting acute pain – ‘I swore, I was using curse words,’ one recalls – none of the medical staff saw a serious problem. When the truth first leaked out, the women’s sense of betrayal was profound, not least among those who had Donna as their nurse: ‘I remember asking her if it’s normal to be in that much pain. And she looked at me and said, yes.’

The Yale patients interviewed here come across as capable and articulate: they include a college lecturer, a public defender, and – fittingly, perhaps – an expert in addiction. Yet something about this clinic and procedure very swiftly robbed them of all power. Some of this no doubt echoes what happens on a lesser level to many of us in medical settings. Shorn of our usual context, we trust the professionals, making twitchy little bargains with unexpected developments, ‘mustn’t complain and make anyone dislike you’ or ‘a bit of pain is to be expected’.

But here the women’s vulnerability was intensified by the fact that they were undergoing gruelling IVF treatment, in which the emotional stakes – and often financial ones – were extremely high. Already, they felt implicitly judged and defined by the absence of a pregnancy. Leah, the college lecturer, explained she was careful not to seem overdramatic in the Yale clinic, because ‘you are treated like a hysterical woman from the moment you walk in there’. Unbelievably, even though one woman – a doctor herself, who often administered sedation – said straightaway that she had twice been given saline, not fentanyl, no one took steps to investigate. She felt she had to go ahead anyway, ‘because otherwise I was going to ovulate and lose all of my eggs’.

This podcast, from the New York Times andthe makers of Serial, takes its time without ever wasting ours. The calm, clear tones of the narrator, Susan Burton, guide the listener intelligently through the many compelling layers of the story, and different varieties of pain. Its reverberations travel beyond the clinic into homes, workplaces and eventually a courtroom, where the women listen to Donna’s sentencing hearing, and the sad complications of her personal life. A crucial factor in lightening her prison sentence – and a particularly piercing irony for her victims – is that she is a mother to three children.

Some radio programmes are appealing not just because of their subject matter but the atmosphere they pump into the room. That’s how I felt about Radio 4’s examination of the art of the late American photographer Diane Arbus, whose relentless eye sought out whatever was skew-whiff in the world and stuck a frame around it. Or was it more that her frame made the ordinary appear skew-whiff? ‘I really believe there are things that nobody would see unless I photographed them,’ she said.

The writer and presenter Alvin Hall, a clear enthusiast, talks to an eloquent cast of fellow Arbus admirers – artists, photographers, writers and curators – about why her photographs remain so distinct. ‘What is the meaning of these stark portraits – images of adults and children, circus performers, queer people, celebrities, socialites?’ he asks. Her biographer Arthur Lubow has one answer: ‘She looked for the flaw in the presentation.’ Titles such as ‘Child with a toy hand grenade in Central Park, NYC 1962’ give you a sense of the jolting blend of the innocent and disturbed in her work. There’s an enigmatic strain of sadness too: the same year that Arbus took the oddly haunting ‘A woman with her baby monkey, NJ 1971’ she also took her own life, aged 48.

The soundtrack is subtly laced with jazz and police sirens, and you can either close your eyes and be drawn into this New York salon or keep them open and google the Arbus titles as they discuss them. Either way, it’s a pleasure.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in