Giant hogweed is a troublesome and expansive species. But it is not, as the tabloids inevitably describe it every summer, ‘Britain’s most dangerous plant’. Many garden favourites – yew, laburnum, castor-oil plant (the source of ricin), for example – can actually kill you. The answer to living with these difficult but beautiful organisms isn’t knee-jerk eradication, but learning what they are and how they live… and then keeping a respectful distance.

Back in the early 1970s, meandering round the wastelands near Heathrow, I came across a giant hogweed wrapped round with ‘Keep Out’ tape. I wasn’t sure if it was a genuine security warning, or a jokey art installation. This was the time when the hogweed’s toxic qualities were first noticed and the press had jumped at the opportunity for hyperbole. An increasing number of children were being admitted to A&E with nasty weals and blisters on their faces.

The source of the problem was tracked down to an umbelliferous plant whose hollow stems children were using as blowpipes and telescopes. It was found to contain photosensitising chemicals called furocoumarins that are activated in strong sunlight, causing skin inflammation and sometimes severe and long-lasting burns.

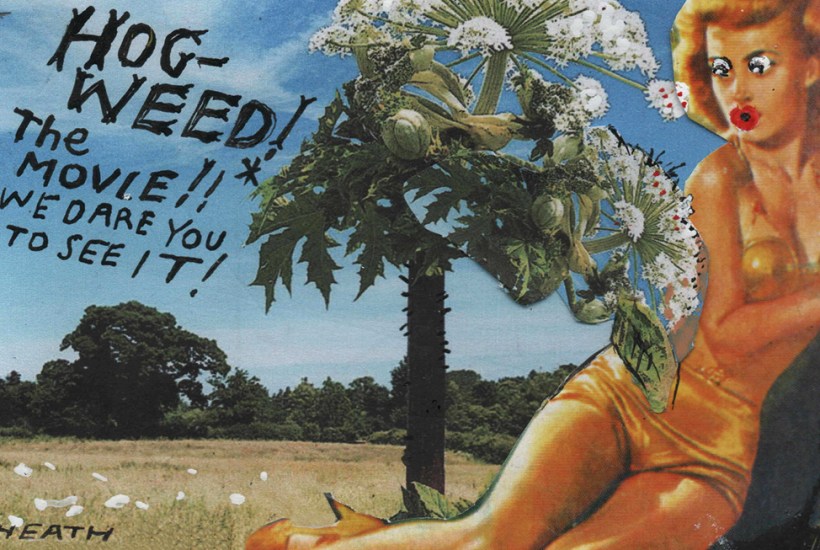

When the popular press discovered that this little-known, seemingly dangerous species could grow up to five metres tall and carry flowers the size of cartwheels, they dubbed it the Triffid, after the monstrous plant in John Wyndham’s sci-fi classic. The fact it had originated the other side of the Iron Curtain gave it an extra stigma, and it was labelled a national enemy, a floral Red under the bed.

Which was all slightly odd, as by then giant hogweed had been about in the UK for a century and a half without any inkling of its dermatitic effects. It was introduced from the Caucasus as an ornamental, and by the 1830s was being praised by garden writers for its majestic architecture. By 1849 seeds were being sold commercially, as ‘one of the most magnificent plants in the world’. The advertisements stressed its democratic credentials, that for a few pence ordinary gardeners could have a display to rival the exotic marvels in the hothouses of the rich. How tastes change.

Inevitably the Hog (a popular tag) began to break out, especially where water was close. A collection in Buckingham Palace gardens edged into the Royal Parks and thence into London’s canal system. This may have been the source of the spectacular colony round the Art Deco Hoover factory in west London. The immense sweeps blanketing the banks of the Clyde have been described by the senior lecturer in botany at Glasgow University as ‘one of the most remarkable natural history sights’ of the area.

This tendency to invade disturbed natural habitats is the chief reason why the 1981 Wildlife and Countryside Act made it an offence to plant or knowingly tolerate it in the wild – though not in gardens, as is being claimed by some commentators. We had awesome specimens in our garden for a couple of years, seeded I think from the dried skeleton we hoicked back from a nearby field to use as a troll-like (and much admired) Christmas tree. No one came to any harm.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in