All things considered, probably the least of George Osborne’s concerns on the occasion of his second marriage was being showered with orange confetti by a woman apparently sympathetic to the Just Stop Oil protestors. Bingo: a whole new form of protest came into being.

What is the whole confetti thing about anyway? You used to be able to tell if there’d been a wedding at a church by the amount of pastel-coloured horseshoe and bell shapes ground into the pavement outside. It was sold in boxes decorated with wedding motifs. Nowadays, no eco-chic guest would throw paper confetti; dried flower petals are the way to go, available in tasteful cones and a useful way of recycling dead flowers. (Really, the protestor should just have thrown marigolds.) The Victorians might have lobbed rice instead.

The roots of the custom lie with the Romans, and probably further back, with the sparsiones, or shower, that was customary at funerals as well as weddings. But in that case stuff was thrown at the crowd by the happy couple as well as at them.

Virgil, in his ‘Eclogues’, tells bridegrooms to ‘scatter nuts’, which he meant literally. Hugh Nibley observed in the Classical Journal that ‘bride and groom could no more evade the obligation of scattering presents to the populace than they could avoid the meal [grains] that the populace threw at them’. Among the things people might scramble for were bits of hawthorn branches for luck – think of the throwing of the bride’s bouquet today. And grains or beans signified fertility.

It’s all designed to mark a wedding as a public event, something for everyone to share in. Not much different then from the Italian wedding described in Charles Dickens’s journal Household Words, where: ‘The bride appeared; there was a merry shout. The bridegroom followed with his friends, and instantly he and his friends began to throw, over the bride’s head, among the assembled folk a storm of comfits [sweets]. Woe to the bridegroom who is mean on such occasions, and economises in his dealings with the comfit merchant! No sweetmeats, no acclamation – for such is the custom of the country.’ The comfits might have been sugared coriander seeds.

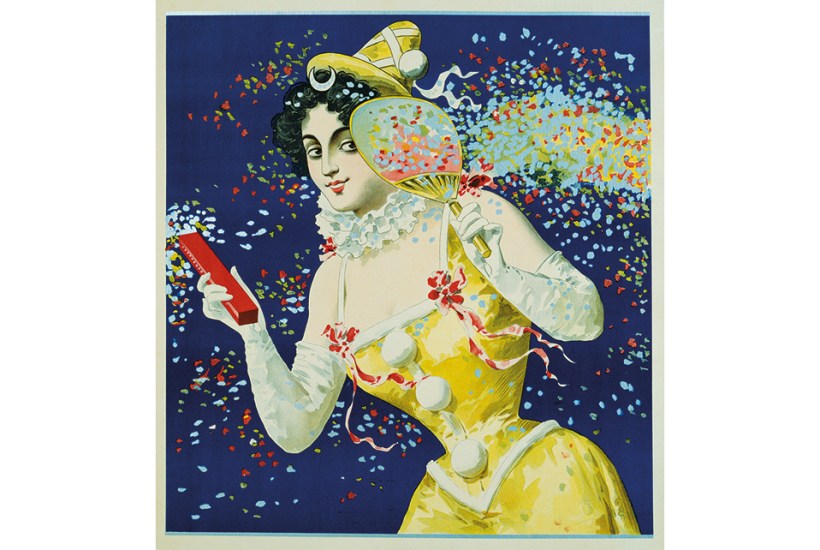

Paper confetti goes back to 1875, when an Italian businessman, Enrico Mangili, began selling it for use in Milan’s annual carnival. Before that the participants in the parade might bombard the crowd with sweets; the crowd might say it with eggs or mud. Milan being a centre of silk manufacture, Mangili began collecting the small paper discs from the punched sheets used by the silkworm breeders as bedding, and sold them for throwing. The product took off for weddings.

Moving from solid items to paper or petal confetti was safer as well as cheaper. In 1820, William Gunter, an English confectioner visiting Italy, observed in his Confectioner’s Oracle: ‘They pleasantly pelt each other with these trifles. But an English country gentleman threw his comfits with such savagery that he actually put out one of the eyes of his young bride!’ George got off lightly.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in