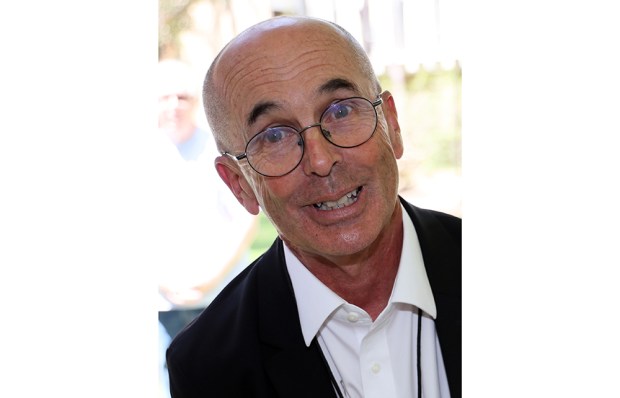

Remember the teenage girl who was murdered in Crow-on-Sea in 2016? A horrific story. Google it. Or the journalist Alec Z. Carelli, the guy who went to school with Louis Theroux, Adam Buxton and Giles Coren and wrote a book about it? Remember how it was pulled because of the controversy over the way he obtained some of his material? Well, the publisher has decided to release that book after all.

None of this is true. Instead, Eliza Clark, the author of Boy Parts and recently named by Granta one of the best of young British novelists, has written an untrue true crime book, a satire on true crime writers and true crime consumers embedded in an intelligently constructed, rapid lounger-by-the-pool piece of crime fiction.

It starts with a note from the publisher: ‘Artistic merit should not be erased from history simply for causing offence.’ The opening proper is a transcript of an American podcast: ‘I Peed on Your Grave, Episode 341’. Next come interviews, summaries, online comments, extracts from other documents, messages and newspaper articles, almost all of which are on the money. Clark describes one character whose daughter was involved in a murder as having written a Daily Mail article headlined: ‘Why Should I Be Embarrassed About Having More Than One Cleaner?’

Throughout the fiction are mucky dollops of real crime, rubbing our noses in our own behaviour. Damien Echols gets a mention, as do Jeffrey Dahmer and Ted Bundy. One character gives tours of Crow-on-Sea, but recalls how they ‘felt icky’ leading Jack the Ripper tours in London. The ‘Columbiners’ are in there, as are the online girls who feel they could have ‘saved’ Elliot Rodger. There are also the sick, deluded Cherry Creek obsessives. Actually those last are made up by Clark, but try to resist looking for them on Wikipedia.

The author is at her best describing this online world, as when she recounts one major event via Discord comments, or subtly explains the fascination with Slender Man and creepypastas (you really can look that one up). The biggest bump in the book is when it shifts to the more conventional and becomes, temporarily, straight crime fiction. ‘My interpretation of a key event’ is how this part is introduced, which feels like a creative cop-out. The story picks up again, but that section might have benefitted froma tighter editorial squeeze.

There are repeated pokes at the nature of true crime, particularly the journalist who admits to feeling like ‘a creep’ when asking people for interviews. ‘Carelli used the shared experience of losing our children to throw me off guard and harvest my content,’ says one regretful interviewee. But Clark shows the way in which things have moved on from Janet Malcolm’s The Journalist and the Murderer. Now some of those who are written about can have a stronger voice than journalists, and if they get their message out there things can turn – as it does for Carelli when his story is scrutinised by those in it, prompting a Guardian journalist to ask him: ‘You’ve referred repeatedly to “emotional truth” – can you define that for me? What does that mean?’

For the most part, Clark avoids social media’s simplistic division of people into goodies and baddies. Instead, she describes characters’ thoughts and behaviour in ways that feel uncomfortably realistic, particularly the teenagers who grapple with shifts of power in their relationships. Who has it? Why do I not have it? The darkness in our brains is also confronted. Playing Sims 4, one character, Violet, locks a Sim teenage girl in a basement and keeps her there. She then introduces a Sim boy, and the pair have babies who are also locked in the basement: ‘Violet considered downloading a mod to enable incestuous relationships.’

People are drawn to that darkness in true crime, and Clark has simulated it well enough that readers will likely google fictional places on real maps. Importantly, nobody was harmed in the making of this book. There will be no upset loved ones –except perhaps those who were affected by some of the true crimes mentioned. The truth about these was probably needed to give depth to the illusion. Still, it is almost ethical true crime. For true crime fans who are not drawn to crime fiction it is a good vegan burger: good enough that there is no need to chop up a real carcass.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in