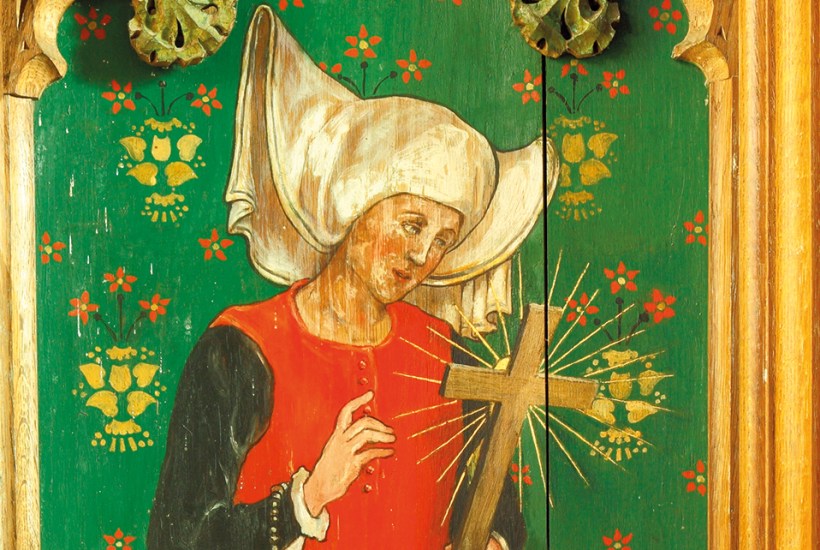

Claire Gilbert considers Julian of Norwich to be the mother of English literature, and believes she should stand alongside Chaucer. What seems indisputable is that Julian was the author of the first work written in English by a woman. This rather wonderful fictional autobiography was published to coincide with the 650th anniversary of Julian first experiencing, in May 1373, the series of 16 visions she wrote about in Revelations of Divine Love. It comes garlanded with praise from, among others, Jeremy Irons and Rowan Williams, the former Archbishop of Canterbury.

In Gilbert’s account, Julian was just a child when she watched her father, a Norwich wool merchant, die in agony from the plague, and when her visions begin she assumes she too is dying of the pestilence – as her husband and daughter have done. Gilbert uses her own experience of cancer – in particular the dreadful constipation she endured as a result of the anti-sickness medication she was prescribed – to evoke Julian’s ordeal of bodily pain. As she has said: ‘Some things are universal: we had bodies then, and we have bodies now.’ There are also vivid descriptions of the multiple miscarriages – ‘13 graves in my heart’ – suffered by Julian’s friend, Isabel.

The anchoress’s consciousness is beautifully captured. ‘I have never felt so alive,’ Julian says at her ‘funeral’, when she enters the walled cell which she will inhabit for decades. There is an implicit feminism in her decision to choose this ‘room of my own’; few women of that period would have had such privacy in which to write. The cell has windows – one on to the outside world, at which people could seek her counsel, another into the adjacent church – and her daily needs are attended to by her maid Alice. Julian is warned many times that she might go mad, and she certainly struggles: ‘I feel like a wild animal caged. For ever.’

The clarity of the prose is striking, as is the ultimate serenity of Julian’s contemplation. She became a source of inspiration during the recent pandemic when many, experiencing isolation, sought out what are perhaps her most famous words, also used by T.S. Eliot in the Four Quartets: ‘All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in