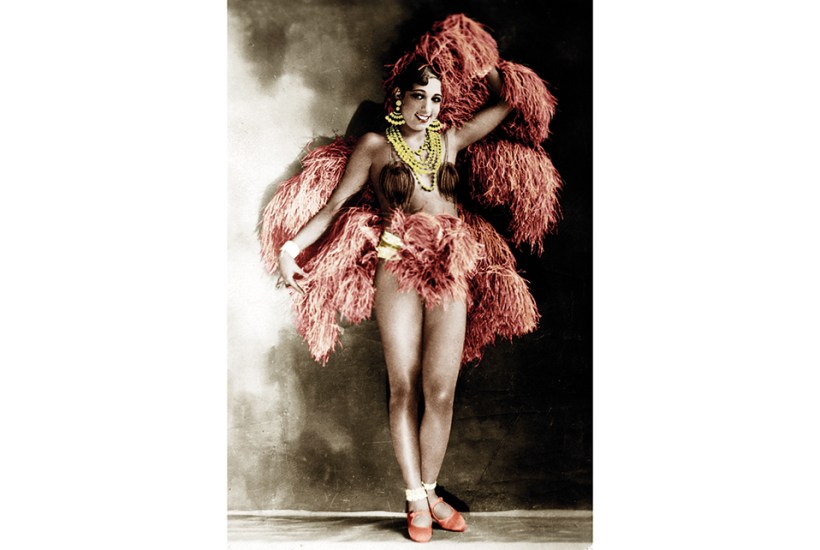

The 1930s saw Walter Benjamin write The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Marlene Dietrich rise to fame in The Blue Angel and Pablo Picasso paint ‘Guernica’. If history books mention these events, it’s usually as footnotes to the main European narrative of the pre-war decade. To shift the rise of Nazism, the Spanish Civil War, the Great Terror and other landmarks to the background, one could turn to the cultural history, or the micro-history.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in