Since 2015, it has been common and rational for people in Westminster to ignore the Liberal Democrats. After the end of the coalition government, the Lib Dems suffered repeated electoral losses and misjudged or mishandled big political events: the fact that the most clearly anti-Brexit UK party has ended up with just 14 MPs today tells you a lot about Lib Dem effectiveness in recent times.

The 2023 local election results probably mean that Westminster needs to update its thinking and start paying more attention to the Lib Dems and the policy positions that have helped them win in places such as Stratford-on-Avon, Windsor and Dacorum in Hertfordshire.

If there is a finely balanced parliament after the next general election, as these results suggest, there is a strong possibility that those Lib Dem policy positions could matter a lot. And probably not in a good way, because local Lib Dem gains may make it even harder for Britain to build more of the things it needs, such as new houses.

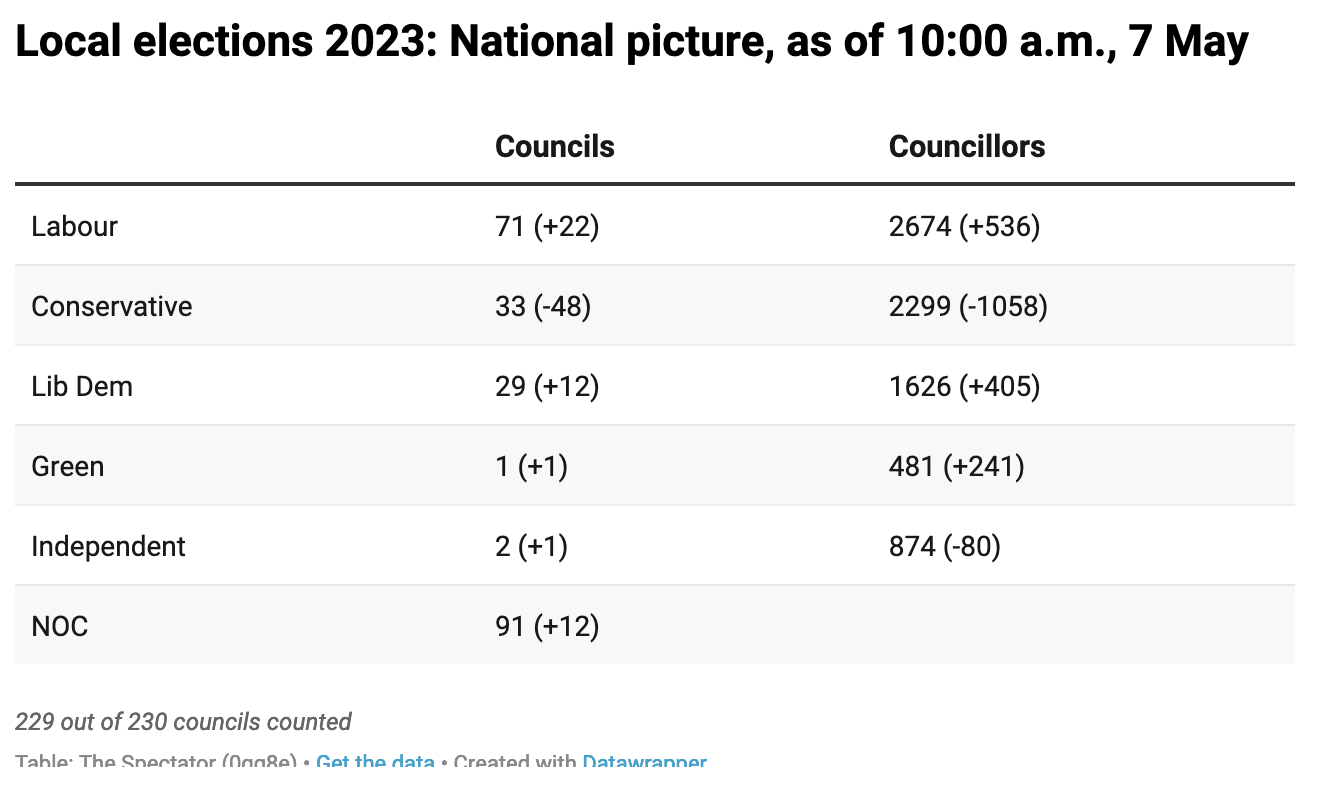

The headline story of the local elections shouldn’t surprise anyone who’s looked at the wood rather than the trees of British politics this year. The Conservatives are unpopular and the fact that Rishi Sunak is more popular than his unpopular party doesn’t matter very much. Likewise, the fact that Keir Starmer is a bit less popular than his modestly popular Labour party.

Map those opinions onto seat numbers and you quickly conclude that the central range of outcomes for the next election stretch from a modest Labour majority, through various hung parliament scenarios and onto a 1992-style comeback for the Tories.

In almost all of the outcomes on the spectrum, the Lib Dems would matter much more than they do now. It wouldn’t take a major improvement in their fortunes to see them returned with 20 to 30 seats in the next parliament, or maybe more. That would mean Lib Dem votes in the Commons would be potentially very important to any prime minister.

It is, I think, very hard to see the Lib Dems returning to a formal coalition government, even with Labour. The experience of government was traumatic for many Lib Dems, and any new coalition deal would raise fears of another tuition fees-style compromise, where party leaders ignored the strong preferences of their voters.

A bigger and more fundamental question is what the Lib Dems would do if they ended up with some power and influence in the next parliament: what are they for?

Here I should declare an interest. In 1994/95 I worked for a Lib Dem MP (Alan Beith of Berwick) and while I was never a party activist, I worked alongside quite a few people who would become Lib Dem members and aides in the coalition 15 years later.

The Lib Dems I knew had some fairly clear positions on policy: they favoured personal liberty, a strong but not overwhelming state, internationalism and an economy with a vibrant private sector. They were also almost proud of taking unpopular stances on things they thought were right – technocrats rather than populists, if you like. It made perfect sense for them to join the Cameron coalition and to abandon a tuition fee pledge that many of them always privately thought was a stupid and populist giveaway.

Much of that technocrat Lib Dem party has since fallen away, replaced by liberal populists and a few practitioners of identity politics. Partly under pressure from the Greens, partly because of the disproportionate influence of some organised activists, the Lib Dems remain committed to the gender self-ID agenda that Labour and (some) Scottish nationalists are now reconsidering.

Probably the most important bit of the current Lib Dem platform is on development: they’re against it.

The defining feature of Lib Demmery at the local elections has been aggressive Nimbyism. ‘Blue Wall’ gains in once-Tory areas such as Surrey and Hertfordshire are based not on a coherent liberal philosophy but on pledges to oppose local developments in and around comfortable commuter towns. A party that used to pride itself on knowing JS Mill’s essay On Liberty by heart is now all about leaflets promising to defend the Green Belt to the death and using public money to pay existing homeowners’ mortgages. It may have a yellow rosette, but this is still populism, the sort of thing Lib Dems used to proudly oppose.

Maybe that won’t really matter too much in the grand scheme of things. Maybe the Lib Dems will remain marginal players in the next parliament.

But that can’t be considered a certainty. And here, the local populism of anti-building Lib Dems could matter a lot, not least since today’s Lib Dems are inclined to obey rather than override local voters’ preferences.

In a finely-balanced parliament, a Starmer government with a small or negative majority and a PM with a fairly weak personal brand will find it hard to deliver big, controversial and important change.

Changing planning rules to allow Britain to build more stuff is about as important and controversial as it gets for Britain in the next decade or two. A Tory party that finds itself in opposition might well succumb further to Nimbyism in order to regain southern votes lost to the Lib Dems. The prevailing political dynamic created by Lib Dem gains would make it even harder to build more houses. Britain won’t be winning here.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in