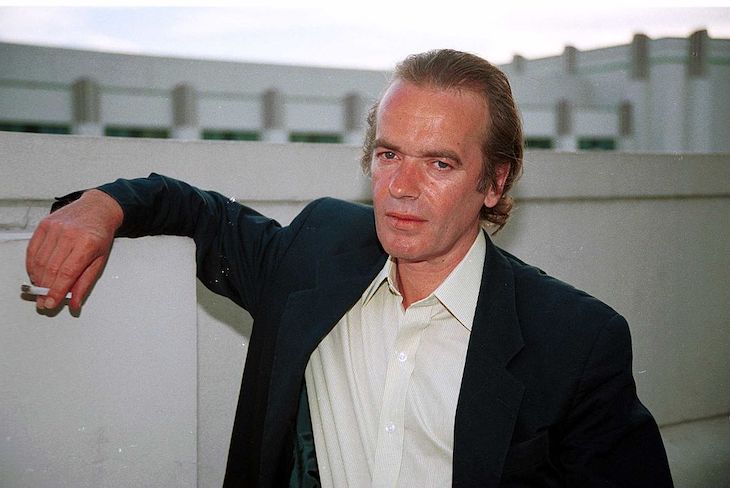

To be a bookish young man in the late twentieth century was to be a Martin Amis fan. I was sixteen when I read The Rachel Papers, and it thrilled me as much as any novel ever has. In some ways more. For here, in its narrator Charles Highway, was a whole way of life. One could be into books, in an ambitious, obsessive way, and also be a cool dude, who smoked fags, chased girls, dispensed witty put-downs, sneered at squares. Here was a comprehensive ideal, mixing high and low, art and fun, the mind and the body, tradition and now. The novel is largely set in West London, and I remember the thrill of a scene set in Notting Hill Gate’s W.H. Smith’s. I knew it well! I belonged to Literature!

One of the lines I remember from that novel is when Charles gives a coin to a beggar who says ‘Gob less’; Charles replies ‘I’ll try’. How cool, to render ‘God bless’ ‘Gob less’. How cool, to reply ‘I’ll try’. And how cool in a general way, to toss a coin to a beggar, like a prince to a peasant, and twist the response so wittily, in a way that slightly puts God in his place. That’s who I wanted to be, aged sixteen and seventeen.

Martin Amis was a magician with words. But was he anything more than a children’s entertainer?

I lapped up a few more of his books. Above all, I was drawn to the voice of swagger, hauteur, disdain, of effortless intellectual superiority. Was Amis aware of the cruelty of such a voice, and sending it up? Up to a point – to be generous. There were a few glimpses of a more humane perspective, but they were quickly and wittily batted away. I remember a blind man in London Fields being helped across the street and then crying. He was used to people being cruel or oblivious – it was when they were kind that it got to him. In fact much of his comedy comes from an awareness that life has a sad, grim side that must be made light of, lest it take over.

It was now clear that Amis was only an averagely good novelist

I progressed, of course, to Nabokov, Amis’ own hero. Humbert Humbert, Lolita’s narrator, is the ultimate witty stylist, the cruel superior artist. As with Amis, it’s hard to say whether Nabokov is adequately critical of his creation. We are meant to admire this voice, full of verbal verve and aesthetic joy, despite the nasty arrogance. But Nabokov is at least clear about the tension – he makes his narrator a paedophile and murderer. The problem is that Amis wants to rescue Humbert’s voice from perdition. One can live for style, one can delight the world with one’s verbal fireworks – even if there’s a bit of cold arrogance involved, it’s an ideal to aspire to.

Once I was in my mid twenties, Amis’ appeal was fading. I liked The Information – there was a fierce muscular force in the prose. But it was now clear that he was only an averagely good novelist – he was really a stylist, a prose-poet. And I admired the same intensity in his criticism. But in criticism, as in novel-writing, style isn’t really enough. You also need convincing ideas as to how literature is meant to relate to life. I was not convinced by Amis’ vague creed, that style can save us. Even if ‘style’ has a sort-of-moral dimension, and demands attention to particularity and a hatred of cliche, it still isn’t enough.

In many of the tributes this week, I sense the desire to prop up a creaky cult of style as salvific. One acolyte, James Marriott, recalls being thrilled by his collection of critical essays, The War Against Cliché.

‘He taught us to write: to avoid repetition and alliteration in our prose, to be on guard for inept jangling rhymes, and even to try not to use two words of a similar etymological derivation on the same page. There is a difference morally, you see. For literature matters like life. We were warned against, ‘not just clichés of the pen, but clichés of the mind and clichés of the heart’.

Partly thanks to Amis, this creed has become the vague orthodoxy of British (male) writers. There is moral worth in good writing, in prose that is tight, taut, bold, smart. In a way it’s the last refuge of the macho wordsmith. In fact some female writers are full acolytes too: Zadie Smith springs to mind.

But it’s not true, or not very. In the Venn diagram of morality and good writing, the overlap is small indeed. An aversion to literary cliche, to poor prose, is a paltry basis for a moral vision. For example, Amis dismissed religion on the grounds that it was the domain of received opinion, second-hand thinking, cliche. It’s a judgement that sounds swish and impressive for a brief moment, until you reflect that all human culture is a dialectic of inheritance and innovation, and that there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamed of in this fag-end of lit-crit.

How nice it would be if the overlap were bigger, and one could focus one’s prose-style, confident that morality would fall into line with such a noble project, for how can a brave wit and a writer of elegant intelligent fearless prose be a flawed person? Such a desire ought to fade with adolescence.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in