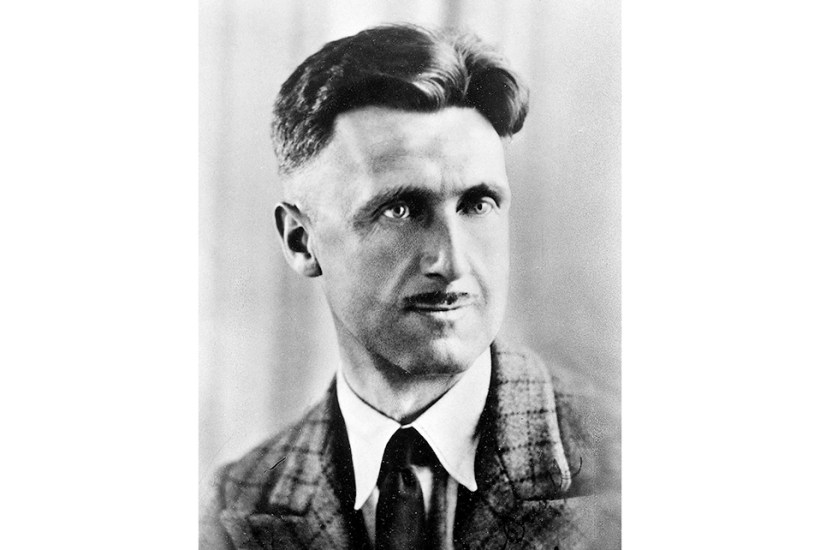

While George Orwell was staying with his family in Southwold during the 1930s, figuring out how to become a writer, the town pharmacist was busy shooting ciné footage. On the edge of a crowd watching a circus parade, he captured a tall man smoking at a street corner. It’s impossible to identify this brief glimpse as Orwell, but D.J. Taylor sees the self-conscious figure holding himself apart as a possible sighting. It doesn’t seem all that revealing, so why does it matter? It feels somehow symbolic of a wider effort to grasp something tangible and candid of a writer who can too readily be obscured by his own myth. This might be a chance to get a look at the man himself rather than a stage-managed persona. As he puts it in Orwell: The New Life, Taylor sets out to uncover ‘the difference between the kind of person Orwell was and the kind of person he imagined himself to be’. This is a book which tells the story of how and why George Orwell became George Orwell, what that means and why it matters.

This is Taylor’s second biography of the writer, which must be a rare feat. The first, published 20 years ago to much acclaim, coincided with the centenary of Orwell’s birth. This one appears a little past the 70-year anniversary of his death. It is not a revised edition, but a new biography. Nor, however, is it entirely separate. There are still entanglements, for example in the essayistic interludes that punctuate the book – ‘Orwell’s Face’, ‘Orwell and the Rats’ etc – which are repeated and kept near enough in both. Why write the same life twice?

One good reason for a second attempt is that archives have been opened and new material discovered since the first book came out. Another is that any biography is only a single encounter with a person’s life and can’t capture anything like a complete picture. Having a second stab recognises that the first go wasn’t, and couldn’t have been, definitive. It’s all a matter of changing perspectives. This chimes with the approach of the whole biography, which collects different points of views and changing ideas – Taylor’s, Orwell’s and other people’s – about what the subject was like. For example, when Orwell’s first book, Down and Out in Paris and London, was published, his family were taken aback by ‘the discrepancy between the man they knew and the life he appeared to be living’. This was the moment when Eric Blair took on the pseudonym George Orwell to protect his reputation and their feelings, so this discrepancy must have been apparent to him as well.

The question of writers’ personas, not least his own, seems to have been on Orwell’s mind. He frequently used his experiences in his novels, to the extent that it caused his publisher headaches about libel. He wrote in the essay ‘Why I Write’: ‘One can write nothing readable unless one constantly struggles to efface one’s own personality. Good prose is like a windowpane.’ In thinking about Orwell’s biography, these two ideas side by side are revealing. It’s a curious combination of openness and evasion, revelation and concealment; efface the person to make the prose transparent.

Taylor sets the much-quoted idea of prose being like a windowpane alongside some of Orwell’s other provocative generalisations, such as ‘all tobacconists are fascists’ and his tendency, noted by V.S. Pritchett, to begin arguable statements with the phrase: ‘It is unquestionably true that…’ Taylor points out that many books Orwell admired ‘achieve their effects via stealth, if not downright obfuscation’, not by simplicity or transparency. Why would he say something he didn’t seem to completely believe, especially about truthfulness? Why would he claim to efface his own personality within writing which, on the face of it, was about himself? There’s a curious conflict here, or as Orwell put it a ‘struggle’, between the wish to follow the angels of his better nature and a demon which, among other things, is ‘vain, selfish and lazy’.

One noticeable thing in this book is Taylor’s description of Orwell as ‘his’ writer. Because I was an ardent teenage Orwell fan too, this struck a chord. ‘Why should Orwell have this effect?’ Taylor asks. Orwell is in some quarters a sainted figure, and idolising simplification is one of the targets of this book, which proposes that contradictions were at the core of Orwell’s life and writing. Taylor says that if you were to boil Orwell’s ‘message’ down, it might be expressed as ‘Behave Decently’, but perhaps that is easier said than done. This biography reveals how the fracture between the person Orwell wanted to be and the person he was runs through his life and work. Perhaps that struggle was part of Orwell’s point.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in