War has broken out in theatreland. Managements are increasingly at odds with the audiences who fund their livelihoods. A recent stand-off involved James Norton’s new show, A Little Life, which contains a couple of scenes in which the actor removes his clothes. A punter at a preview in Richmond secretly photographed the moments of nudity and posted the images online. This sparked a furore in the newspapers and the majority of commentators took the producers’ side against the theatre-goers. Dr Kirsty Sedgman, a media studies lecturer, spoke piously to the Independent about ‘an absolute violation of the unwritten contract between audiences and performers’. The Mirror reported that ‘drastic measures’ might be needed to ensure that similar ‘privacy breaches’ don’t occur. No one considered that the backers of the show were secretly thrilled by all the free advertising. And it seems bizarre to invoke the ‘privacy’ of an actor who chose to appear naked in public and who spoke to the press about his on-stage striptease. Richmond Theatre itself handed out leaflets reminding punters that photography was forbidden and this almost certainly encouraged the illicit snapper to get to work.

Theatres are now being urged to crack down on playgoers carrying smartphones. A well-known publicist suggested that every device must be covered in duct tape before its owner can enter the venue. Alistair Smith, editor of the Stage, predicts that smartphones will have to be deposited in lock-boxes at the start of each performance. But what if the punters refuse to surrender their devices? We may end up with a stop-and-search policy in every foyer. That may sound unthinkable but the Covid crisis taught the public to act meekly in the face of intrusive regulations.

The fundamental problem here is that theatre administrators don’t much like the audience. The same is true of directors and actors who regularly declare that the rehearsal period is their favourite part of the job. Why? No spectators getting in the way. A playgoer is a wilful and unpredictable creature who forms an independent and sometimes negative impression of a show. Worse still, he shares his critique with other potential customers. For theatre managers the ideal production would involve 20 shows performed to an invited crowd of fans, agents and family members. The presence of the paying customer can only taint this pure and exalted form of dramatic expression.

To many theatre-makers, the audience is simply a conspiracy against art. And this hostility finds its way into the control-freak rules imposed by every playhouse. During Covid, the level of enforcement intensified but the strong-arm tactics haven’t disappeared. Many theatres order their ushers to blast every visitor with ‘a cheerful earful’ of prohibitions. ‘Phones to silent. No re-admission’, they honk at us. ‘No bags in the aisles. No entry for latecomers. No photography. No smoking. No wine glasses in the auditorium.’

A popular playhouse in west London likes to kettle the crowd outside the auditorium until six minutes before the show begins because ‘the set is being dressed’. Well, hardly. The previous performance ended 22 hours earlier and it’s inconceivable that the stage-hands are still tinkering with the furnishings and the decor. In reality, this theatre has found a neat way to inconvenience the customers. This arbitrary and irrational practice can have only one possible cause: a wish to micro-manage and control. This contemptuous attitude towards punters seeps into a theatre’s dramatic output. Artistic directors, especially in the subsidised sector, are happy to ignore the audience and pursue a narrow and inflexible manifesto of fashionable interests approved by the metropolitan elite.

Since the end of Covid, new battlefields are emerging. A spate of physical conflicts has been reported to Bectu, the Broadcasting, Entertainment, Communications and Theatre Union. Brawls are breaking out between audience members. Drunken playgoers have been seen urinating in stairwells. Front-of-house staff complain of being spat at or punched, and a third of theatre employees have witnessed an incident that required police intervention. Theatre managers haven’t yet found a solution to this problem because they’re keen to ply the punters with as much over-priced drink as possible. Many playhouses now offer an ‘at-seat app’ that delivers crisps and champagne to anyone who wants to avoid the scrum at the crush bar. If you treat your audience like a booze-cruise crowd you can’t complain if they descend to that level. An anonymous respondent to the Bectu report said: ‘The price of drinks is so high that people come pre-loaded or they smuggle things in.’

A production of The Bodyguard at the King’s Theatre, Glasgow, was marred by rowdy singing which led to complaints from ticket-holders who wanted to enjoy the professional cast. The same production was shut down when it reached the Palace Theatre, Manchester, after two audience members insisted on singing along and the police had to be called to eject them. The theatre management in Glasgow issued a warning to audience members on social media: ‘You can help by ensuring the professionals on stage are the only people entertaining us.’ In other words, shut up and keep your tuneless screeching for the karaoke bar. This created a bizarre precedent: a singalong musical that allowed nobody to sing along.

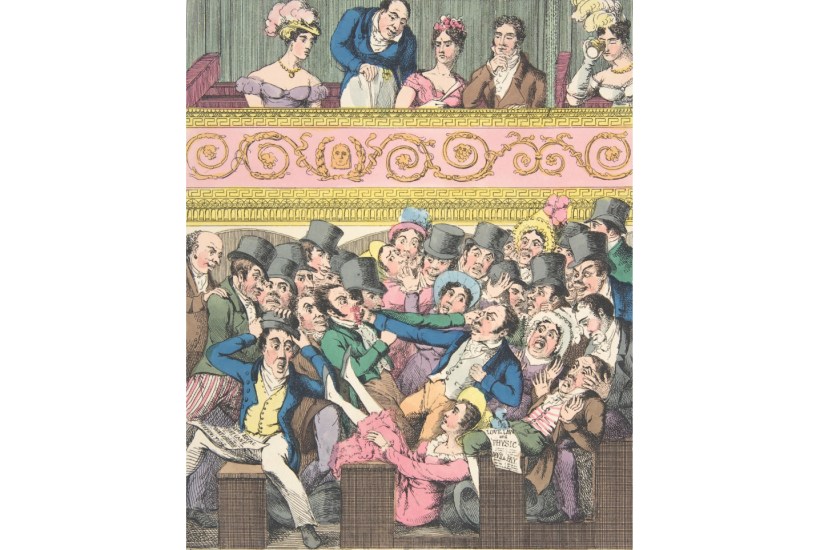

Today’s audiences behave a lot better than in previous centuries. When David Garrick began his career it was common for playgoers to saunter into the venue via the dressing room. And audience members felt free to lounge on stage throughout the show. The proscenium arch was introduced in part to create a barrier between the playing area and the seats. Not that this stopped the crowd from lobbing gingerbread and cooking apples at the cast and sometimes at each other. If a show failed to please, the auditorium would erupt in a chorus of ‘mooing’ noises. There were fights too – often over rises in ticket prices. During the 18th century, the Drury Lane Theatre was smashed up by audiences on six separate occasions.

And although we haven’t reached that level of chaos, our theatre culture is becoming steadily coarser. The furore over James Norton certainly doesn’t help. Never mind the issue of smartphones or the confected outrage over a naked performer’s ‘privacy’. Look at the bottom line. Even with prices at a whopping £145, nearly every seat for A Little Life has been snapped up. That sends a powerful message to commercial producers. ‘Get an actor to disrobe and you’ll sell out.’ We’re in danger of turning the West End into a strip club.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in