The National Curriculum is broken. So too is the profession of instruction and teaching. Each new Education Minister – be they state or federal – arrives with a commitment to ‘start turning things around’, while admitting that ‘it is a difficult task, of course’.

The stated task is difficult because, despite the good intentions of these ministers, ‘decent folk’ (that is the phrase we use now, isn’t it?) do not know their subject matter. They believe that education is a neutral human activity. They believe that it is simply a matter of more targeted funding or raising teacher training standards…

All their energies are wasted if they do not understand the nature of the beast they are trying to tame. The IPA’s Bella d’Abrera and Colleen Harkin have found one important starting point. Our National Curriculum in Australia is more about pretence than about teaching and learning good information to do good for others. That is, modern education smuggles into ‘essential teaching’ particular theories of life and action that smother the learning and thinking of our young – and those theories, as ideologies, are systems of belief in which the designers put their faith. It is why they are insisted upon in the category called ‘general priorities’ – teachers are expected, to the point of loss of accreditation, to include the biased version of Australian history in all subjects; and also, the skewed understanding of science as it applies to what used to be called ‘good stewardship’ and is now called ‘sustainability’. D’Abrera and Harkin correctly call this out as the ‘new paganism’, which is in fact pseudo-science. Their long lists of examples across subjects are worth reading.

Kevin Donnelly has been warning us of this since he co-authored a review of the National Curriculum in 2014. In his later work, he also highlights the problem. We have lost confidence in teaching students about what is important to sustain a civil society (not that we use that term much anymore). But, contrary to our contemporary beliefs about humanity, without the self-discipline that is required to be civil, we become willing rabble needing increasingly soft and ultimately harsh authoritarians to ‘keep us safe’ and to ‘be kind’. Peter Hitchens (brother of the late Christopher) saw this clearly when he returned from the horrors of communist China. In 2010 he noted that any education linked to Christianity would be overthrown. When back home in the UK, he also observed that it was those inestimable number of small acts of charity done by those who were taught to ‘do unto others as you would have them do unto you’ and ‘praying for your enemies’ that undergirded ‘better society’. But because those principles are some of the main teachings from the Bible, he saw they would have trouble surviving.

This shift in beliefs and focus areas have had dramatic impacts on the competency of teachers to both instruct and teach. Instruction is what we can call the transfer of information and skills. E.D. Hirsch has described well how a misunderstanding of how students think has left them the poorer in what they have learnt. Faddish ideas about ‘letting them sort out what they need to know’ combined with ‘the internet has all the information’ has bred generations of teachers who have given up on introducing students to those moments in history and the accumulation of facts within that history that has made our current world possible.

I agree with other tertiary teachers who say things like, ‘My students are keen to learn – the problem is that they know nothing.’ Here is one example from my education students. Over the last six years, I have asked the question: ‘What difficulties did Australian Aborigines have, as a society, before contact with Europeans?’ As one of my more mature students said this year (the others were too shy to say it), ‘To be honest, I don’t know. I’ve never been taught that.’

Yet their opinions about Indigenous matters are really strong. It reminds me of that quote ascribed to CS Lewis: ‘There is nothing as dangerous as a 15-year-old with a strong opinion, who knows nothing.’ Actually, there is something more dangerous – it is educational leaders with strong opinions (or climate ministers) who know nothing.

It is why researchers like Tom Sweller and the John Hopkins research institute are having to explain why our brain needs to learn bits and pieces of information on which to build expertise over time. Information is essential in building critical thinking that has some correspondence to ancient wisdom (to paraphrase Lukianoff and Haidt). Critical thinking is built on knowledge – and not vice versa. As the IPA, Donnelly, Sheridan, and others have been warning in Australia, it is not helpful to trust the fantasy that if we learn to ‘think critically’, we can find the information we need. Rubbish – a pianist does not stop to problem-solve the next complicated piece of music. She draws on the years of rehearsal of smaller skills (and skills are information applied to practice). The same is true for engineers, physicians, lawyers, teachers, and their students.

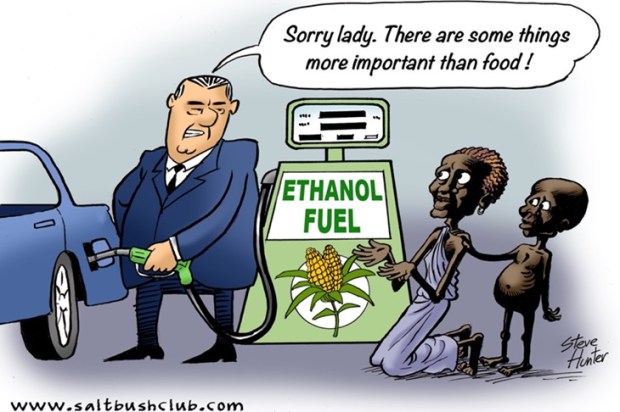

So, our soft-headed ideas about being ‘student-led’ and ‘the automated information revolution’ has meant that we have given up on decent instruction. That is also why we cannot teach. Teaching (beyond instruction) is about inviting students to care about what they are learning about. But to learn to care about something in a fruitful way, we need to know what has gone before us. And again, as the IPA has demonstrated, understanding what has gone before us has been shot to pieces with revisionism that is not only partisan, but self-defeating. Teaching untruths has an impact on the hearts of students who are looking for truth. When they are fed untruths, their thinking becomes clouded, their passions become distorted, and eventually debased. Instead of having people who can talk sensibly about the achievements of even the last 50 years, and what we can do to build on those achievements (reading Bjorn Lomberg’s material would be a good example), they become crippled under the lie of alarmist predictions. An immature Christian will try and give an exact date for the end of world. An immature environmentalist or race theorist does the same. None help us to ‘love others as we love ourselves’.

Fascinatingly, it was a scholar in the 5th century who first understood and articulated the proper relationship between instruction and teaching. It became clear to him when he took to heart his mother’s prayers for him. Augustine was to write, in about 427AD:

So the speaker who is endeavouring to give conviction to something that is good should despise none of these three aims – of instructing, delighting, and moving his hearers [to do good]…

What will it take for our educational leaders to understand that we must instruct in knowledge, do it in a way that our students want to keep learning from us (and yes, students do enjoy learning adult knowledge!), and move them to consider building on the wisdom from the past towards a wiser future? D’Abrera and Harkin suggest scrapping the National Curriculum. I suggest that before we look at any rebuilding, we have an honest look at who we are as human beings, as learners. A bloke called William James had some interesting ideas in 1901 when he spoke of accepting both the seen and unseen aspects of life. But thinking about and discussing that idea might be dependent on all those involved having to understand more knowledge than the modern mind can bear.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in