British nature is having a moment, thanks to David Attenborough’s Wild Isles (BBC One). As ever, spring brings a crop of new nature writing, but you are unlikely to come across anything like Once Upon a Raven’s Nest. This is the story of the life of an Exmoor man – Hedley Ralph Collard, known as Tommy – and it reads like bloody-knuckled rural noir. Fans of Niall Griffiths and Kevin Barry will bolt it down. But although the tale is told by Tommy, and rampages along like fiction, the book is actually a blend of reportage and imaginative truth constructed by Catrina Davies, who writes: ‘Where necessary I have put my own words into his mouth, and filled in the gaps of his story using my imagination. This is a portrait, not a biography.’

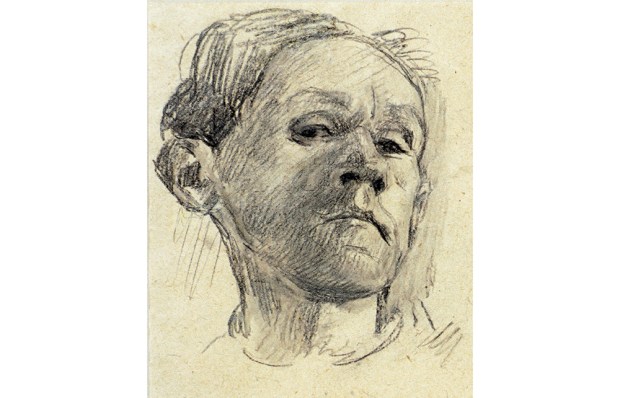

She met Tommy towards the end of his life and interviewed him extensively. Rendering his experiences in his own voice allows us to approach a violent, passionate, often mad, harsh and deeply observed world (the actual world of the countryside, which few ‘nature writers’ get anywhere near), through the eyes of an exuberant man of the kind who rarely write books.

You know it is going to be good from the moment Tommy climbs a tree to escape his enraged father. He takes refuge in a raven’s nest. His father orders him down:

I’m going to ask one more time, he says, raising the axe so I can see the blade glinting in the moonlight.

No, I says. I’m not coming down, because you’ll beat me.

Father stands there a moment or two longer, then he raises up the axe and he cuts the tree down.

This is a world where wedding cakes are cut with chainsaws, bailiffs are shot at, salmon is fished with explosives, deer are hunted with crossbows, refractory livestock is punched out and baby bunnies scragged from their warrens with briars twisted in their fur.

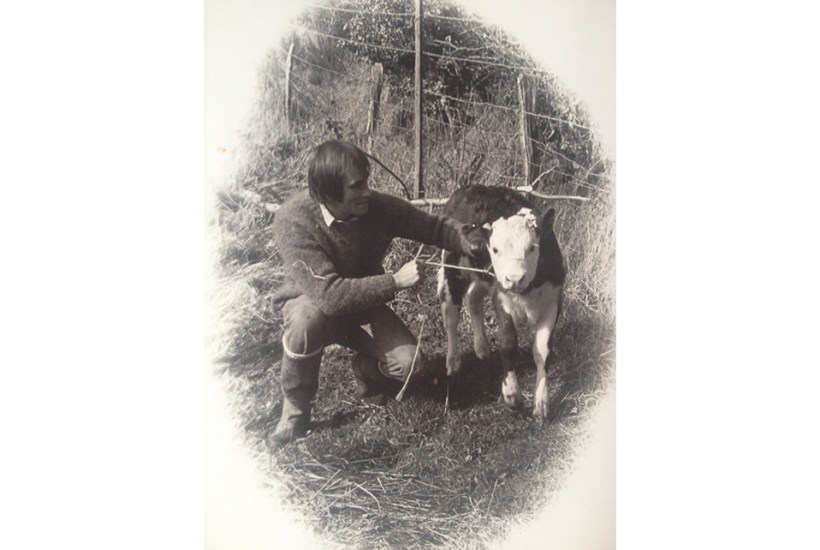

Tommy was a stockman, forester, National Park warden, poacher, photographer – and the most accident-prone protagonist in contemporary literature. I lost count of the bones he broke and quad bikes that rolled over him. The book could make a film, but it would cost a fortune in wrecked machinery and crippled stuntmen.

Best of all is the intertwined epic of Tommy’s love life. A general silence seems to surround the inner life of the straight male. Yes, I know we have designed and defended the whole mighty catastrophe that is the world today, and hoarded to ourselves its powers, wealths and glories; but how much do we hear or read about the raw truths of men’s hearts and minds (assuming they are different)? Who is writing about their real and terrified desires, tender longings and clenching fears? The educated, artistic and intellectual slide some of it obliquely into novels, films, poetry and plays. But listen to Tommy, recorded or scripted by Davies, and something gripping and honest emerges. Because his arc of the narrative is only vaguely linear – stories told in looping, associative disorder within the brackets of his birth and death – there are moments when the married woman with whom he had an affair, the woman who became the love of the end of his life, and the wild woman who married him briefly before vanishing with a note (‘Sell stock, I’m not coming back’) all animate the same few pages.

Davies and Tommy between them manage an illuminating clarity. Perhaps because he was mature when he recounted his tales, teller and writer are able to show how men can be smitten by a physical form; how they can be humbled and awed by the strength and selflessness of women; how those feelings can lead them to silence, not speeches; and how much courage and self-knowledge it can take to tell a woman who wants one what she does not want to hear.

The other arc of the book is an account of catastrophic environmental damage and collapse. Davies keeps breaking the story every few pages to include another dreadful fact. It is all true and urgent, of course, but the device becomes distracting and irritating. How can we care about the fate of the planet when our hero is on the point of halving himself on a circular saw? Strip that thread out and this is a superb book.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in