Julie McDowall ‘first encountered Armageddon’ in September 1984 when she was only three. Her father was watching a BBC Two drama called Threads about a nuclear attack on Sheffield, but instead of putting her to bed (which he obviously should have done) he let her watch it too. She saw ‘milk bottles melt in the nuclear heat, blackened fingers claw out from the rubble’ and was convinced this was really happening. ‘The experience scarred me for life,’ she declares, ‘and it is the reason you are reading this book.’ In her twenties, she suffered panic attacks and agoraphobia, so she decided to confront her fears by becoming a journalist specialising in the nuclear threat. This book – and it is a very good one – is the result.

Her narrative begins in the optimistic 1950s when Britain was coming out of post-war austerity and Harold Macmillan was telling people they had ‘never had it so good’. The future was all peace and prosperity and new washing machines. Except that in 1952 Britain exploded its first atomic bomb, in a nuclear test off the coast of western Australia, and in the same year America exploded its first hydrogen bomb. Albert Einstein warned that ‘successful radioactive poisoning of the atmosphere and hence annihilation of any life on Earth has been brought within the realm of technical possibilities’. Churchill commissioned the Strath Report on what would happen to Britain in the event of a nuclear attack, and its conclusions were grim: ‘Life and property would be obliterated by blast and fire on a vast scale… No part of the country would be free from the risk of radioactive contamination.’

How could the population be protected? Before the start of the second world war, the authorities predicted that air raids would bring mass panic: ‘London, for several days, will be one vast, raving Bedlam; the hospitals will be stormed, traffic will cease, the homeless will shriek for help and the city will be in pandemonium.’ But in fact the population proved remarkably resilient. A Mass Observation survey in 1941 showed that the majority of people were not emotionally affected by the war at all, and 20 per cent of women were actually made happier by it.

Could the same thing happen with nuclear attack? Could the population get used to living underground, in smelly bunkers, only venturing out occasionally in search of food? Well, no. Because even if people survived a nuclear blast, they would still have to cope with radiation fall-out, which could last for weeks, and there would be no food to be found.

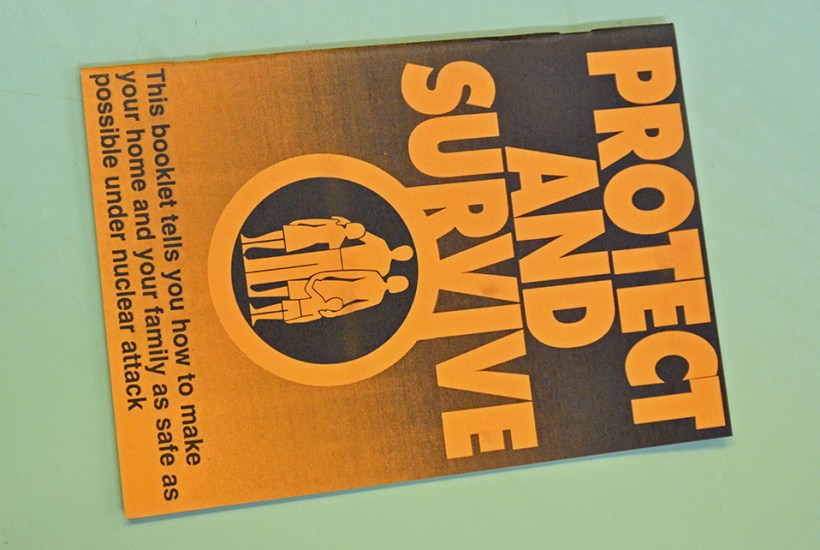

The authorities discussed the idea of evacuation, but quickly abandoned it when they realised that no part of the country would be safe. And anyway how could they house and feed evacuees? The message to the public had to be: stay home, fortify your house with sandbags (though someone worked out there was not enough sand in the whole of Britain to protect even a city the size of Hull), board up the windows, stockpile food and water, and make sanitary arrangements. This was the advice given in the 1980 leaflet Protect and Survive,which rather assumed that ‘home’ would be a largish suburban house with a garden, and a spare room to store food, and not, say, a maisonette or flat.

News of a nuclear attack would be broadcast by the BBC, which would interrupt its programmes to say: ‘Here is an emergency announcement. An air attack is approaching this country. Go to shelter or take cover immediately.’ This would be accompanied by the sound of local sirens, switched on by the police, which meant the population had just four minutes to take shelter. In practice, of course, when sirens went off by accident as they sometimes did, most people ignored them.

CND’s line was that all this civil defence advice was bunkum because nobody could actually survive a nuclear attack. Some councils declared themselves nuclear-free zones and refused to make civil defence plans but were told by the Home Office that they must. So South Yorkshire put out a particularly lurid leaflet, You and the Bomb, and distributed it to 500,000 homes. It advised that you need not worry about disposing of corpses close to the epicentre of a nuclear detonation because they would be vaporised; but if someone died in your home, the corpse should be wrapped in polythene, but not too tightly, ‘as pressure of the gases produced by a body decomposing is likely to rupture the bag and the resulting smell is likely to create unnecessary offence’.

McDowall says that although British nuclear attack sirens were generally dismantled in 1993, a few still exist – one atop a pole in Lewisham and one on a railway bridge outside Waterloo. ‘I seek them out. I hunt these ghosts and snap them with my camera.’ She also visits old nuclear bunkers and describes them in her Atomic Hobo podcast. She thinks we should have kept them, as did Germany, Poland and Ukraine, because ‘for as long as nuclear weapons exist, so does the threat of nuclear annihilation’. This is a sobering book, but a gripping one.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in