Charles Darwent’s Surrealists in New York is somewhat misleadingly titled, though its true content and focus are revealed in the subtitle: ‘Atelier 17 and the Birth of Abstract Expressionism.’ Perhaps that sounds obscure and even academic. If so, it gives the wrong idea, for this is a very readable and accessible account of a hitherto unexplored area of mainstream art history. Many of us suspected the importance of European influence on what is always claimed as the thoroughly American art movement of Abstract Expressionism. This book sets out the situation in detail, and makes a convincing argument for giving credit not only to a bunch of European émigrés but to an Englishman as well.

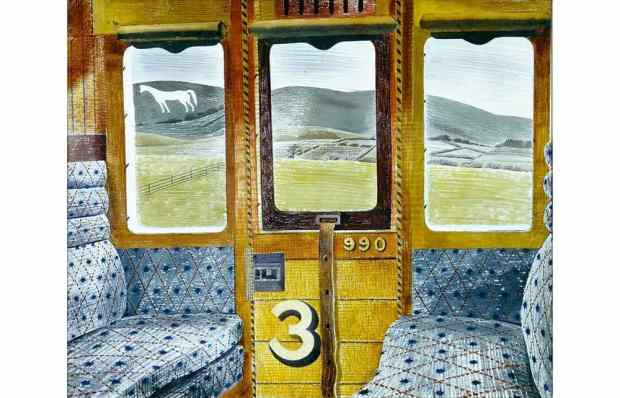

Darwent’s contention is that the English painter and printmaker Stanley William Hayter (1901-88), who founded and ran an experimental print workshop called Atelier 17, first in Paris and later in New York, was a crucial influence on the development of Abstract Expressionism in America. The period under discussion is essentially the 1940s, with the first Parisians arriving in New York at the start of the decade. There Hayter gathered around him the (mostly French) Surrealists who had fled the Nazis, and it was in his workshop that young American artists such as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell and Willem de Kooning could meet and see the work of the European masters Max Ernst, Joan Miró and André Masson. Set up at West 12th Street, on the seventh floor of the New School for Social Research, later moving to East 8th Street, Atelier 17 was primarily a print workshop, but it was also a substitute café for the French, a favoured meeting place for the exchange of ideas and enthusiasms.

Among the visitors to the Atelier were Alexander Calder, Louise Bourgeois and Anaïs Nin. The last was very impressed by Hayter, whom she called ‘a stretched bow or a coiled spring’, while her American husband, Ian Hugo, became the most faithful of Hayter’s disciples. Atelier 17 was very much a place of collective activity, and this didn’t suit everyone. The young Motherwell made a handful of prints with Hayter, but was uneasy in the studio. He later told the curator John McKendry that although he felt a natural affinity for working on copper plates, he stopped printmaking at that point because he much preferred to work by himself. Likewise, Pollock worked when no one else was there, often at night.

This is an important book on two counts: for its welcome reassessment of Hayter, and for the light it sheds on the links between the Surrealists and the Abstract Expressionists. Certainly it subtly alters the landscape of modern American art. Darwent writes authoritatively, marshalling a wide range of entertaining anecdotes and quotations to sustain his thesis. There’s lots of fascinating technical detail about printing, often taken from first-hand accounts of the period. The story of Atelier 17 is plumped out with sections about how various Surrealists transplanted to America. Several of them – their putative leader André Breton, Yves Tanguy and André Masson – never learnt to speak English, which led to a certain isolation. Masson probably benefited most, finding it invigorated his work, but he also claimed ‘it is devouring me… I think I would be dead if I stayed there’.

The book is a complex account of putting theories into practice: ideas about how to subvert the way the eye habitually moves, of transposing front and back and destabilising preconceptions, of attacking the work from all sides, not from one fixed viewpoint. Hayter likened the turning of the plate beneath the engraving tool to the way the Earth appears to turn beneath a banking plane. He himself was able to throw a line on to an engraving plate with all the spontaneous brilliance we associate with Pollock. In fact, Hayter’s influence on the young artists who worked with him must be seriously reconsidered, and one of the uses of this book is to make us question our assumptions. Darwent writes of Hayter and Pollock as colleagues and friends, as co-explorers, not master and pupil.

You may ask why all this has not been written about long ago and given a firmly established place in the history books. For a start because Hayter was no self-publicist, and kept scant record of what he did. (There is no trace, for instance, of the prints de Kooning made at Atelier 17 around 1943. The plates of Motherwell’s and Bourgeois’s engravings are also lost.) Hayter later said he had engraved 300 plates and helped to make 5,000 more, but he never even kept proofs of the best ones. He was too modest and self-effacing for the good of his subsequent reputation. Now we are being asked to look again at his aims and American circumstances, and it makes engrossing reading.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in