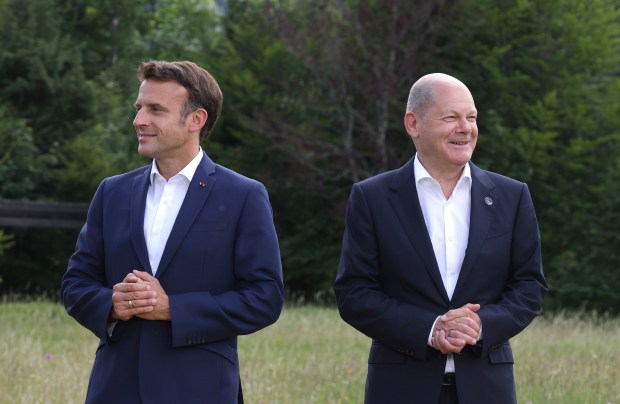

The editorial in today’s Le Figaro heralds the dawn of a 21st century Entente Cordiale and the newspaper carries an interview with Rishi Sunak. Speaking ahead of today’s Anglo-French summit in Paris, Sunak says he wants to ‘open a new chapter with France’.

Le Figaro pins the blame for the deterioration in relations between the two countries since the last summit in 2018 on the British, specifically Boris Johnson and his ‘anti-French populism’. The French believe that is now a thing of the past with Sunak in No. 10. This conveniently overlooks the fact that if Johnson was the bête noire of the French, Emmanuel Macron hasn’t exactly been the most diplomatic leader.

Macron doesn’t respond well to criticism, and nor does he like it when things don’t go his way

When he was elected president in 2017 Macron boasted of turning France into a ‘Start Up Nation’. Square Up Nation might be more accurate given the president’s penchant for seeking confrontation, and not just with Britain.

As recently as Sunday, Macron was arguing with Felix Tshisekedi, president of the Democratic Republic of Congo, during a joint press conference in Kinshasa. Tshisekedi accused France of paternalism and implied it was responsible for some of the country’s travails. Grow up, was the gist of Macron’s retort, telling Tshisekedi not to search outside the DRC ‘for culprits’. He added: ‘I’m sorry to say it in such blunt terms, but it is not France’s fault if since 1994 you have not been able to restore the sovereignty, neither military, nor security, nor administrative, of your country.’

He had a point but perhaps it would have been advisable to couch it in more diplomatic language. But that’s not Macron’s style, particularly when he’s in Africa. Six months into his presidency, the then 39-year-old president visited the continent and pitched himself as the new fresh face of France. ‘I am from a generation that doesn’t come to tell Africans what to do,’ he assured students at the University of Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso. So when one of them asked Macron what should be done about the country’s frequent power outages, he replied that it was not his responsibility but that of his host, President Roch Marc Kabore. A few moments later Kabore left the stage to answer a call of nature. ‘You see,’ said Macron, waving him on his way, ‘he’s left to fix the air-conditioning.’

Social media accused Macron of being ‘arrogant’ and ‘paternalistic’, criticism he dismissed as absurd. When a French reporter asked if he would have cracked a similar joke in the presence of Angela Merkel, Macron replied: ‘I would have with Angela Merkel, with any head of state’.

Certainly, the French president he has never ceased to speak his mind, and to hell with whom he upsets. In the same week that he caused a rumble in the jungle in Kinshasa, Macron was riling the Moroccans. They took umbrage at his breezy assertion that the relationship between the two countries was ‘friendly’. That was news to Morocco. ‘Relations are neither friendly nor good, neither between the two governments nor between the royal palace and the Élysée Palace,’ snarled a spokesperson. Morocco has accused France of sullying their good name at Brussels while simultaneously cosying up to their rival Algeria.

Not that Macron has ever been flavour of the month in Algiers. The latest spat was about the activist Amira Bouraoui – a French-Algerian opponent of the Algerian government – who was arrested last month in Tunisia. Before she could be extradited to Algeria, France arranged for her to fly to Paris. A furious Algeria recalled their ambassador in protest, accusing France of causing ‘great damage’ to Algerian-French relations.

Across the Mediterranean in Europe Macron has managed to fall out with the leaders of Italy, Hungary and Poland, while also antagonising Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy, on account of his conciliatory words towards Vladimir Putin.

Macron seems to have a particular beef with the Poles. In 2017 he was described as ‘arrogant’ and ‘inexperienced’ by Prime Minister Beata Szydło after she was accused by Macron of ‘infringing’ public freedoms. Szydlo’s successor, Mateusz Morawiecki, strayed into Macron’s sights last year and was called ‘a far-right anti-Semite who bans LGBT people’. Morawiecki’s mistake was to have criticised Macron for continuing to talk to Putin after his invasion of Ukraine.

Macron doesn’t respond well to criticism, and nor does he like it when things don’t go his way. Put it down to the inexperience highlighted by Szydlo.

Macron was effectively parachuted into the presidency a year after forming his own political party. A banker by trade, he is not a political animal who has grown up in the cut and thrust of debating, arguing and compromising. One suspects he wouldn’t last five minutes in PMQs without blowing a fuse.

Macron’s sulkiness is legendary, as he demonstrated in September 2021 when he summoned home the ambassadors to the USA and Australia. It was the first time France had recalled its ambassador to the States but such was Macron’s fury on learning of the Aukus security pact. The accord between America, the UK and Australia entailed the cancellation of a £48 billion contract that Canberra had signed with a French company for a fleet of 12 submarines.

Macron appears to have patched things up with the Aussies after Anthony Albanese replaced Scott Morrison as PM. Will a new face in No. 10 lead to a similar revival in Anglo-French relations? Macron needs as many friends as he can right now; he’s got none in France and few internationally.

The problem, explained Laurent Bigot, a former diplomat, in a recent TV interview is Macron’s approach to diplomacy. Describing it ‘as the art of nuance’, Bigot said Macron doesn’t do nuance and as a result he has a habit of antagonising world leaders with his bluntness. To make matters worse, last year Macron got rid of the country’s Diplomatic Corps, a controversial move many believe will only make him more prone to gaffes on the global stage.

Last summer Liz Truss famously declared that the ‘jury’s out’ on whether Macron was a friend or foe of Great Britain. The indignant response in Paris was comical, coming from an administration that the previous year had threatened to cut off the electricity to Britain in a row about fishing rights.

If Macron and Sunak are to get through the day without falling out the president would be well advised not to get on his high horse about Brexit. Britain has left, get over it. But feel free to make a wisecrack about the other ‘B’ word. In fact a joke or two at Boris’s expense might actually score Macron some much-needed brownie points in Britain.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in