It’s payback time: women, artists from ethnic minorities and non-western traditions are taking over the exhibition schedules. On the heels of the seven women expressionists in Making Modernism at the Royal Academy comes Souls Grown Deep like the Rivers: Black Artists from the American South. ‘We are aware that art history has excluded a lot of artists and it is incumbent on us to broaden our perspective,’ said Academy secretary Axel Rüger at the press view – and for anyone who failed to grasp the magnitude of the moment one of the artists, Lonnie Holley, added: ‘This is the Royal Academy of Arts. This is not just some come-by-lately museum, hear what I’m saying?’

The 34 artists from the Black Belt states of Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi look completely at ease in Piccadilly. It’s not just the inventiveness of their work but the scale of its ambition. At 8ft square, Thornton Dial’s ‘Stars of Everything’ (2004) – a constellation of splayed housepaint tins twinkling around a bastardised American eagle dressed in rags – dominates Room 1. A self-portrait? Dial calls himself a ‘pick-up bird’, a scavenger. Descended from families left behind in the Great Migration, without access to art education or materials, the artists gathered here made art out of what they had: worn-out fabrics, scrap metal, driftwood, obsolete electrical appliances, house paint. ‘Because we were the slaves, the outcasts, the throwaway part of humanity, that was our playground,’ says Holley. ‘The stuff that was thrown away, we had to reuse it.’

Assemblages? They got ’em. Former steel worker Charlie Lucas’s ‘Three-Way Bicycle’ (c.1985), welded together from bicycle wheels and machine parts, is a Tinguely-esque delight; Bessie Harvey’s ‘Untitled’ (1987), a tree root sprouting faces with teddy-bear eyes and marbles for teeth, is spine-tinglingly surreal. Eldren M. Bailey’s concrete and plaster cast ‘Dancers’ (1960s) – he made markers for graves – bursts with a febrile energy reminiscent of Barry Flanagan’s hares. Self-taught doesn’t mean artistically uneducated. All artists are ‘pick-up birds’, and the traffic is two-way: Robert Rauschenberg’s assemblages owed inspiration to African-American art. For these artists, though, arte povera was a necessity, not an aesthetic choice. In the words of Raina Lampkins-Fielder, curator of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation in Atlanta, Georgia, which has lent most of the works: ‘It is art for art’s sake, and then some.’

From the American South to the American Northwest, where the story of the Indigenous artists in the Sainsbury Centre’s new exhibition could not be more different. The key is in the word ‘Indigenous’. Unlike the African Americans in Soul Grown Deep, uprooted from their ancestral cultures and forced to start from scratch, the Native Americans of the Northwest Coast in Empowering Art had 10,000 years of unbroken tradition to draw on, rooted in carving.

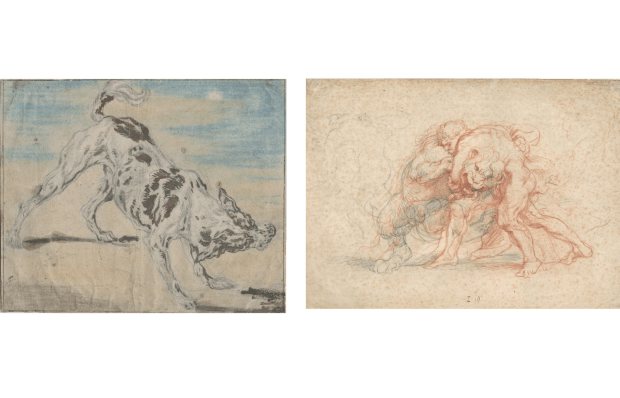

‘Western art is based on the figure, west- coast Indian art starts with the canoe,’ said the celebrated Haida artist Bill Reid. In a society where every man has to know how to carve, the master carver is a true master of the art. The show’s examples of 18th- and 19th-century whistles, clappers and rattles carved with distinctive ‘formline’ designs of bears, wolves, frogs, salmon, hawks, whales and ravens are exquisite. Meant to provide instrumental accompaniment at potlatch feasts, these treasures were snapped up by European collectors after the Indian Act of 1884 banned potlatch, and Indigenous artists turned their hands to making souvenirs.

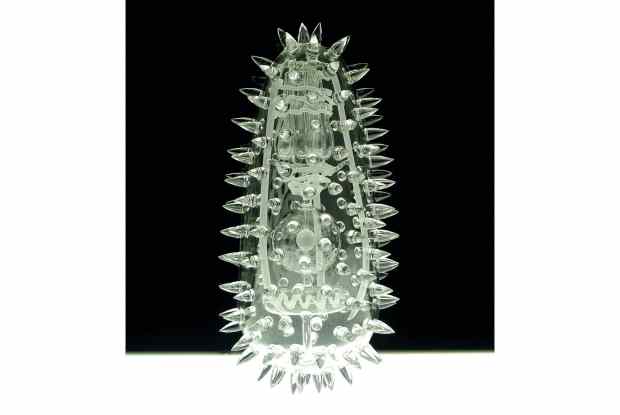

The argillite pipes they carved for sale to sailors are beautiful, but the Indians’ grasp of commerce would be their undoing. Their openness to trade exposed their fishermen and fur-trappers to European competition, bringing missionaries, government agents and disease. Half the population died in the smallpox epidemic of 1862-3. The residential schools in which Indigenous children were compulsorily re-educated in western culture are recalled in two poignant works by contemporary artists. Sonny Assu’s ‘Leila’s Desk’ (2012) recreates the 1930s school desk where his grandmother sat at St Michael’s Residential School, and Marianne Nicolson’s ‘Bax’wana’tsi: The Container for Souls’ (2006), an illuminated glass cabinet engraved with photographs of her mother and aunt as pupils at the school, projects formline shadows on to the gallery walls.

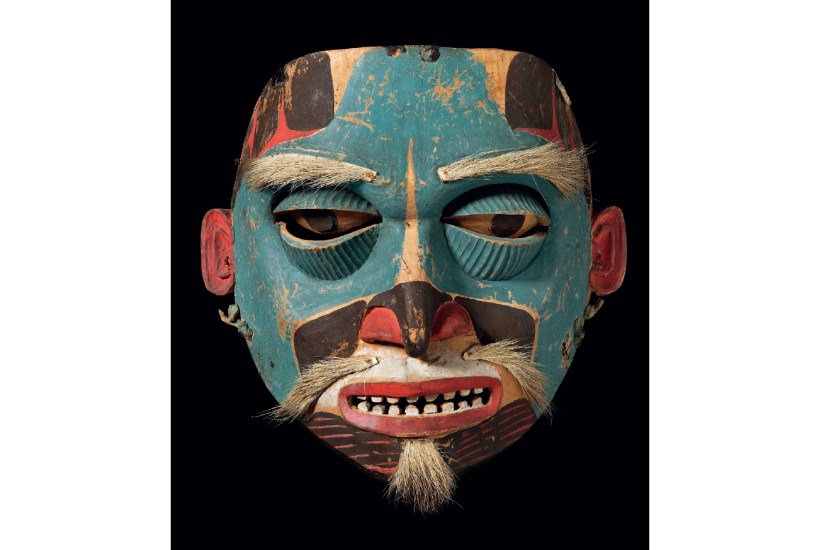

Skeena Reese’s ‘Marlon Brando Trickster Mask’ (2010) pays witty tribute to Brando’s defence of Native American rights but can’t compete with the 19th-century masks at the exhibition entrance. ‘I’m struck by how far from home this material is,’ mused Haa’yuups, the Hupacasath artist whose 40ft dance screen covers a wall of the main gallery. ‘As objects to be appreciated masks are one thing, but when worn properly by a masked dancer in a building filled with a thousand people who’ve been feasting for four hours, they’re something else.’ At some point, five of these ancestral heirlooms found their way into the collection of Colchester and Ipswich Museums. It made me wonder what the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast would make of the hats and bells worn by the Suffolk East Morris men.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in