This book has already had an interesting life, and most readers will by now know something of its history. For any who don’t, Nigel Biggar’s Colonialism was originally submitted for publication to Bloomsbury and was warmly received by them; but two months later it was indefinitely delayed, because (as the ‘email from the very top’ went) ‘public feeling’ was ‘not currently favourable’. Biggar writes in his introduction:

I asked them to specify which ‘public feeling’ they were referring to, and what would have to change to make conditions favourable to publication, but they declined to give answers. Instead, they informed me that they were cancelling our contract. Happily, William Collins has rescued what Bloomsbury chose to jettison.

If the book has got off to a rocky start, it is likely to get rockier still, because it will divide opinion along seemingly irreconcilable lines. Biggar has already had his very public run-ins with the anti-colonialists, and for all its air of disinterested enquiry, his ‘moral reckoning’ is not so much an olive branch as a broadside against an ‘illiberal cancel culture’ and time-serving academics for whom a ‘fashionable’ anti-colonialism is the open door to ‘posts, promotions and grants’.

If nostalgic imperialists will not quite find themselves in Alfred Austin’s garden, happily dreaming of telegrams announcing British victories on land and sea, they will come away from Biggar feeling a lot more comfortable about their past than they might otherwise be. The author never shirks the historic evils perpetrated by the Empire, but in his inquest into Britain’s colonial record we are seldom allowed to lose sight of the other side of the ledger.

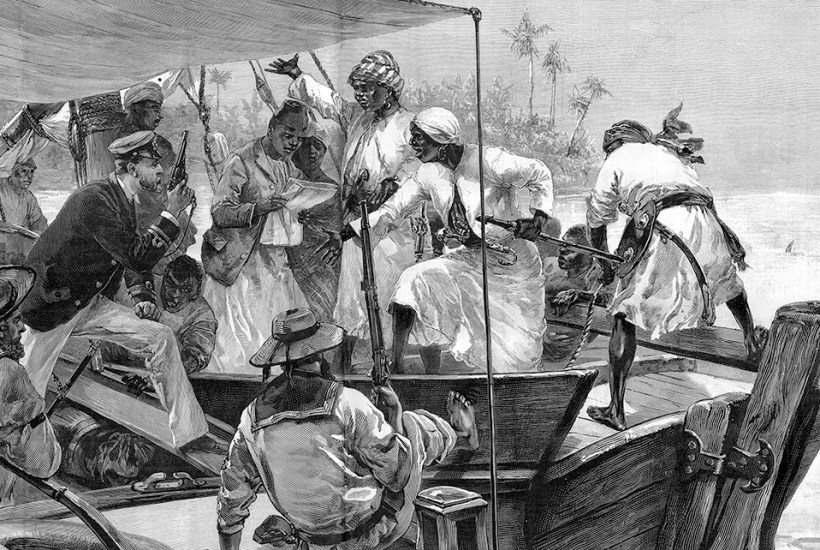

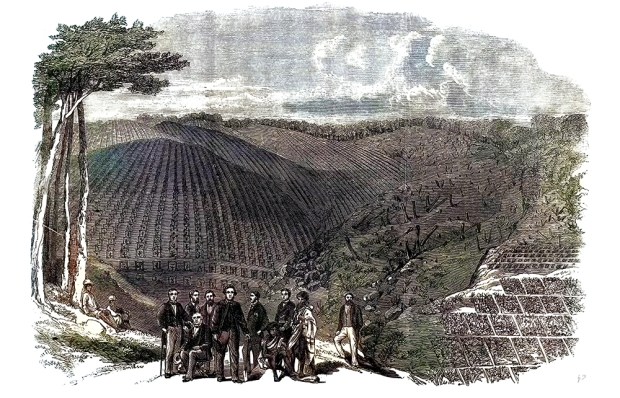

If slavery was vile, what kind of selective ‘amnesia’, the book asks, can have erased the abolitionist movement from public consciousness of our past? Or ‘the century and a half of penance’ for the horrors of the transatlantic trade when the Royal Navy was policing the world to eradicate slavery? And what of the fact that, in 1940, it was Britain and her Empire that fought virtually alone against the Nazi regime? What of the countless district commissioners and civil servants in India who devoted their lives to the countries they served and often loved? What of the establishment of the rule of law? And what – the drum roll of British achievements, economic, cultural, humanitarian, educational, paternalistic, fills a whole page – of that example of ‘extra-ordinarily incorrupt’ administrators that the Empire bequeathed to its former colonies?

None of this, of course, will wash with the anti-colonialists, any more than will the reminder that General Dyer liked Indians; that we were not the first to blow prisoners from the cannon’s mouth; or that the Benin treasures were technically ‘spoils of war’ and not ‘loot’. Much of it, in fact, will seem only just to an impartial reader. But when every concession is made to what Biggar calls ‘a more historically accurate, fairer and more positive story’ of the Empire, there remains an uneasy feeling over the ethical grounds on which his argument is based. He writes at the beginning:

As I see it, whether or not a policy that involves killing – or any other policy, for that matter – is morally right or wrong is not determined simply by its effect or consequences. What decides its moral quality are the motive and intention of the agent, and the proportionality of its means.

It is fair enough to make an ethical judgment on empire – Biggar is, after all, Regius Professor Emeritus of moral and pastoral theology at Oxford – but what it is in danger of becoming here is a kind of moral escape clause from the hard facts of colonial and imperial rule. It might well be sound ethics that he is preaching in his introduction, but when it comes to British colonial history, this approach leaves too much wriggle room for the apologist, too many opportunities to acquit the Empire of racism, violence, ‘land grab’ or whatever the crime might be, and put the blame firmly on some aberrant ‘man on the spot’.

General Maxwell in the wake of the Easter Rebellion; Dyer at Amritsar; the ‘Denshawai incident’ in Cromer’s Egypt; the volunteer settlers in Mau Mau Kenya; murderous farmers in Tasmania; racist jute merchants in 19th-century India; the army’s blood lust after the Mutiny – the pattern Biggar describes seems ominously predictable. He is right to stress the intractable difficulties of controlling an empire as disparate and vast as Britain’s. But in the case of the hundreds killed in the Jallianwala Bagh, or the Egyptian peasants publicly hanged, or the 47 survivors of Tasmania’s original population, his ‘intentions’ seem no more relevant than the official distancing of the authorities.

There are times, too, when Biggar seems to set the moral bar alarmingly low, and he can be very selective in his ‘witnesses’. But the real worry here lies in the nature of a debate that seems to bring out the worst in both sides. Any comparisons between Cecil Rhodes and Hitler or the concentration camps of the Boer War and Auschwitz are patently absurd. But even if it is an irresistible temptation to ‘fight for victory’, to expose every anti-colonialist misquotation or historical sloppiness (and there is no shortage of them), does Biggar really imagine that haggling over the precise profits of the slave trade or tallying up the costs of suppression even begin to address the deep and legitimate unease that empire and colonialism stir?

This is a pity, because there is a lot here that is good. The book is very readable, exhaustively researched, and, whether one agrees or not, presents a case that needs hearing and certainly needed publishing. It is hard, though, not to wonder what, for instance, E.M Forster, that most civilised of voices, might have made of it. Or George Orwell for that matter. And harder still, at the end of 130 pages of densely printed endnotes – many of them rehearsing old ‘skirmishes’, as Biggar calls them, with the anti-colonialists – not to wish a plague on both their houses.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in