The musical revolution of the 1960s reverberated widely. In many countries it was given added impetus by decolonisation. Newly independent nations adopted rock and roll, usually infused with local traditions, as a signal of modernity. From Addis Ababa to Dakar to São Paulo, officials and businessmen jived and swung and caroused in nightclubs, serenaded by bands with some measure of official sponsorship, if not directly employed by the government itself.

Some of these stories ended unhappily. The Brazilian junta dispatched Tropicália musicians into exile. When the Derg seized power in Ethiopia, Swinging Addis came to a sudden halt. The ligueurs in Benin forced Angélique Kidjo and others to flee the country.

But the most horrific tale of all was Cambodia. Prince Sihanouk’s government encouraged the country’s musical flowering after independence from France. When Sihanouk was overthrown in a military coup in 1970, his successor, Lon Nol, enlisted Cambodian pop stars as (largely unwilling) propagandists against the prince, often conscripting them into military bands. And after the Khmer Rouge seized Phnom Penh on 17 April 1975, musicians were reviled as bourgeois reactionaries, even those who had not (like Touch Tana) been married to film idols. From then to the beginning of 1979, something approaching a quarter of Cambodia’s population died in the Killing Fields. The best estimates are that nine in ten musicians were murdered.

Dee Payok’s epiphany came when she visited a rural temple and heard, played on a boombox, Sinn Sisamouth’s ‘Away from Beloved Lover’ – a Cambodian adaptation of ‘A Whiter Shade of Pale’, itself heavily influenced by Bach. She returned to Cambodia a couple of years later for an extended research trip, interviewing singers and musicians who had survived the genocide and the relatives of those who had died. Her book is part travelogue, part musical history and partly a chronicle of deaths foretold.

After a synoptic overview of the whole period, most of it is structured around the interviews. In many cases, the early careers of the musicians have a shape that would be familiar to anyone from Merseyside or Memphis: childhood dreams of stardom or escape (Battambang, in the north east, seems to be the kind of town people are desperate to get away from); living in the big city, hustling for gigs and haggling with venal club owners; schedules as Stakhanovite as the Reeperbahn; the outside chance of immense success and fame.

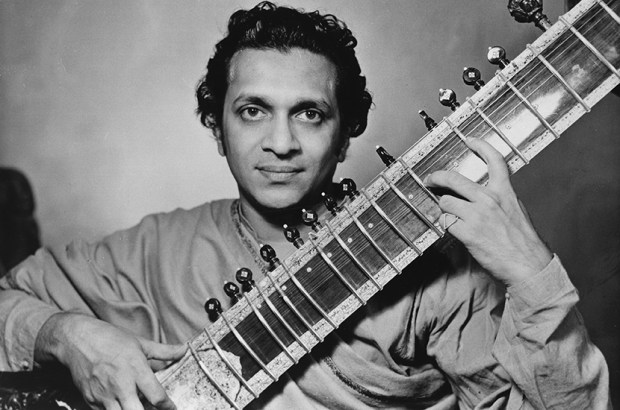

If the 1960s were a time of possibility, the first half of the 1970s was full of compromises. Sinn Sisamouth, a Sihanouk loyalist, went back to his original profession of nursing for a year before he started performing songs such as ‘The King Sold the Land to the Viet Kong’ and ‘Tomorrow I’ll Join the Army’; Ros Sereysothea made propaganda films in which she parachuted out of a plane.

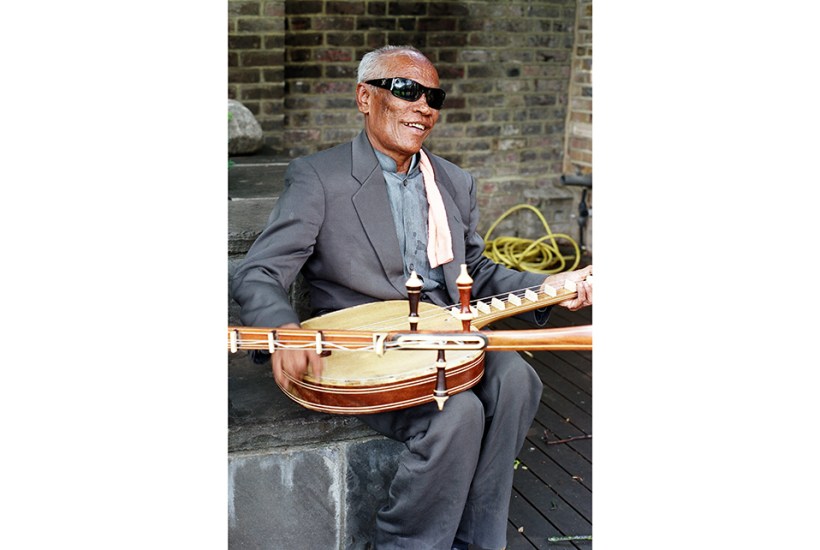

Then came the genocide. Kong Nay, the blind chapei singer, was first pressed into service singing agitprop about ‘The Bourgeoisie Taking Advantage of the Poor’ to the inhabitants of the village to which he had been dispatched, then ordered to strip palm fronds to make brooms, and had been scheduled for imminent execution when his village was liberated. The drummer Keo Sinan buried his prized record collection beneath an outhouse containing chemical fertiliser and managed to keep it hidden throughout the Khmer Rouge years. Touch Tana, the singer with the Floydian psychedelists Drakkar, was set up by his fellow commune residents for stealing fish, but managed to talk his way out of execution.

These are the survivors. The Battambang-born heroines of the Golden Age, the retro-styled Huoy Meas, the tomboy Pen Ran and the towering Ros Sereysothea were all killed by the Khmer Rouge. Sinn Sisamouth, in Cambodian terms a loose amalgam of Elvis and the Beatles, and the composer of at least 1,200 songs, simply disappeared. There are many competing accounts of his death, each more gruesome than the last.

Today, cultural historians are trying to recover the lost heritage, digitising the remaining records and wrangling over copyright. (There is a degree of irony about this, given the cavalier way in which western songs were appropriated.) Modern bands such as Dengue Fever and Cambodian Space Project are reviving the psychedelic era.

Payok’s own work in tracing and interviewing the survivors and documenting the country’s lost artistic scene is so thorough that it feels churlish to mention occasional solecisms. (A random sampling shows the record label Dust-to-Digital referred to as Dust for Digital; ‘contingency’ used for ‘contingent’, ‘aghast’ for ‘agape’; ‘alumnus’ treated as if it were the plural of, presumably, alumnu.) But her structuring of the book as a series of descents into, and in some cases escapes from, the darkness of the genocide gives due weight to the suffering of the Cambodian people, musicians and non-musicians alike.<//>

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in