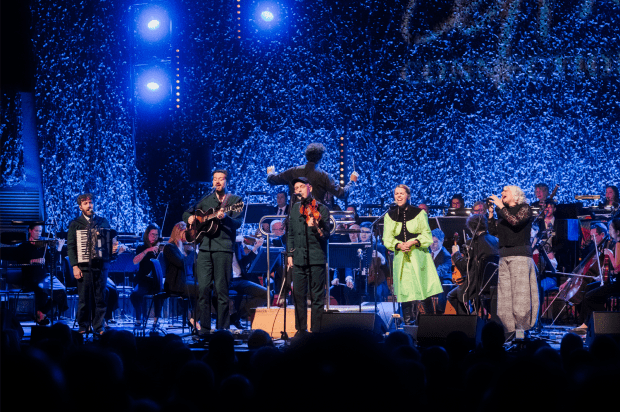

Folk is the Schiphol of Scottish music. Eventually, every curious traveller passes through. From arena rockers to rappers, traditional music remains an undeniable source. Which is why the second word in ‘Celtic Connections’ is at least as significant as the first.

Now in its 30th year, lighting up the otherwise unpromising prospect of a Glasgow January, this year’s instalment of the roots festival features artists from all corners of the globe. Many of them would regard folk only as their second or third musical language, rather than the mother tongue.

One of the early highlights makes the point rather beautifully. It’s a homegrown affair, showcasing pianist Fergus McCreadie and harpist Maeve Gilchrist, two of Scotland’s most inventive solo musicians. Performing separate sets with the venerable and fluid chamber ensemble Mr McFall’s String Quartet, both highlight how ingrained folk is to their respective roving styles.

Youth brings its own fresh perspective. The Quartet first performed in 1996; McCreadie was born in ’97. Twice winner of Young Scottish Jazz Musician of the Year, he is already making inroads into the mainstream. His third album, Forest Floor, won the Scottish Album of the Year award in 2022 and was nominated for the Mercury Prize. You can hear why. He’s a pianist with a strong individualistic streak, and I’d imagine that the likes of Keith Jarrett, Glenn Gould, Oscar Peterson and McCoy Tyner rank high on his list of influences; his solo Chopin at the end nodded fondly to Martha Argerich.

Tonight, however, jazz is infused with the spirit and sound of folk music and the landscape from which it springs. The drone, the sweep, the lyricism and romanticism, all feel atavistically familiar. He even looks like a folkie, with his man-bun and wispy beard.

They begin with three of his own compositions, arranged by Mark Henry with the instruction to ‘take my pieces and make them unrecognisable’. In the end, it’s nothing quite so dramatic. McCreadie’s style is unshowy, accumulative. ‘Across Flatlands’ broods and builds; in a film, this would be the music of pursuit. Gradually, McCreadie takes the lead, runs rippling out from the central motif. The second tune is impish, with a staccato pulse and fluid top lines. The third is more obviously Celtic, romantic and grand.

The rest of his main set is a composition inspired by the life cycle of plants, originally written for last year’s green-themed Dandelion Festival. It’s clever, expressive writing and playing, evolving over four short movements that build to a beautiful solo piano passage and then the playful blossoming of the final section, augmented with brittle, Brubeckian stabs on the off-beat.

For an encore, McCreadie returns with Gilchrist, who had already performed her own set with McFall’s strings earlier in the evening. Edinburgh-born, New York-based, Gilchrist is an extraordinarily versatile harpist. She has recorded with the likes of Arooj Aftab, Esperanza Spalding and Elvis Costello.

Tonight, she is a little more contained than I’ve seen her in the past, but no less expressive. Performing The Harpweaver, her 2020 album, Gilchrist filters traditional folk roots through the prism of crisply contemporary strings, some singing, and (muffled) excerpts from a taped recitation of ‘The Ballad of the Harpweaver’ by the jazz age poet Edna St Vincent Millay. Skipping from laments to hornpipes, the work explores art and nostalgia, crafting new life on old bones. It is beguiling, if a little disunited. When she returns to duet with McCreadie, harp and piano engage in a stately drawing-room dance.

A different kind of folk influence is in evidence at Celtic Connections a few nights later, when Rozi Plain – pronounced to rhyme with ‘Fozzy’ – performs an enjoyable hour-long set. The traditional stimulus here speaks of something a little woollier, redolent of illicit campfires, Somerset sound systems and Jez Butterworth’s Jerusalem. I find myself jotting down phrases like ‘cidery grooves’ and ‘woozy funk’.

Backed by a quietly inventive four-piece band, Rozi Plain is touring her new album, Prize. The music lopes and twists. Songs loop around circular baritone guitar riffs. Wistful, off-centre melodies catch like cotton on barbed wire, strange lines gaining traction through repetition: ‘Things that have heat, things that don’t have heat…’

Animated by a rumbling pulse, ‘Agreeing For Two’ is West Country Fleetwood Mac. ‘Conversation’ is a four-square pop song on three legs. ‘Prove Your Good’ is a hypnotic incantation. There are hints of funk, jazz and the lilt of Afrobeat, and strong echoes of Rozi Plain’s sometime collaborator This Is The Kit, but that folky strangeness keeps bubbling up. The sound of new connections being made via ancient maps.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in