Is Facebook’s scheme, announced over the weekend, to encourage its three billion users to pay $12 (£10) a month to have their accounts verified really just a form of corporate extortion?

I ask only because last year someone – I strongly suspect a deranged Novak Djokovic fan – took the time to create a fake Facebook profile featuring me. The photo that accompanies the profile, which is named ‘Damian Damian’, is certainly of me, although Boris Johnson, who I was standing next to when it was taken, has been cropped out.

Onto my forehead has been superimposed a fetching pair of devil’s horns and posts include ‘I’m a delusional little boy’, ‘I’m an evil journalist with a secret agenda’ and, most charmingly of all, ‘my obsession won, I didn’t order the medicine, I can’t remember the last time I took it’.

I’m fingering a Djokovic fan as the culprit because the profile appeared very shortly after I incurred the wrath of thousands of them on Twitter by posting footage of his team furtively mixing for him mid-match a mysterious drink. Evidently, whoever created the profile has been through my real Facebook profile, because they sent friend requests to all my actual friends, as well as to me.

Why should we have to pay to avoid being impersonated on Facebook?

Mortifyingly, 14 of my friends accepted these requests, including my not terribly tech-literate mother. A friend I haven’t seen since our university days has liked the ‘evil journalist with a secret agenda’ post.

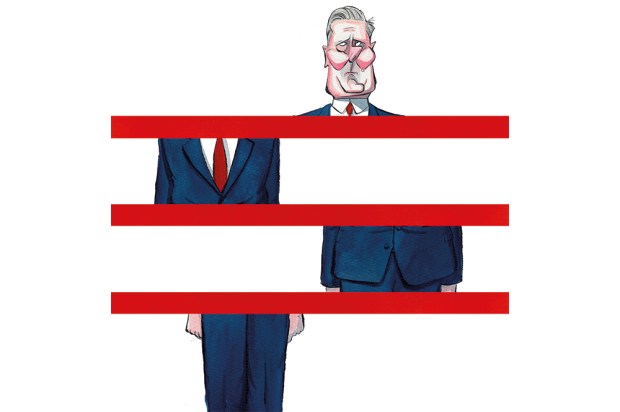

Obviously, I’ve reported the profile numerous times, although it’s impossible to get hold of anyone at Facebook on the telephone. Instead, you have to make your complaint online, by choosing from the various category options with which you’re presented: ‘fake account’, ‘fake name’, ‘posting inappropriate things’, ‘harassment or bullying’ and so on. Naturally, the process was a complete waste of time. When Facebook finally came back to me, via email, it said the profile ‘isn’t pretending to be you and doesn’t go against our community standards’. As a result, it’s still there – my name, my face, my friends, but apparently not impersonating me – for all the world to see. I’ve even tried contacting the Facebook press office, but to no avail.

But now I see that if I just pay for verification, my problems would all go away. Meta founder Mark Zuckerberg says in return for their cash, users will ‘get a blue badge, extra impersonation protection and direct access to customer support.’ But isn’t that precisely how a digital protection racket would work? You stump up the cash on the regular, and the heavies ensure you have no more problems. What else could possibly be understood from that ‘extra impersonation protection’ wording?

But why should we have to pay to avoid being impersonated on Facebook, particularly when that impersonation is intended by users to cause distress? Given the social media platform’s entire multi-billion dollar business model has until now been predicated on the value of user data – the value of us, in other words – surely the least the company can do is to protect that data in a way that affords users basic dignity, without them having to fork out extra for the privilege.

It goes without saying, there are real world repercussions to Facebook bullying, or trolling, as it has come euphemistically to be known. As a journalist accustomed over a period of more than two decades to receiving anonymous online abuse as a result of virtually anything I write – a phenomenon with which I suspect all journalists are wearily familiar – I’m fortunate in that I couldn’t care less about it. In fact, in many instances I’ve come to relish it: I take perverse pleasure in annoying people whose need for anonymity to my mind equates to a fear of sunlight. But I’m well aware this is an unusual attitude.

Were my children, for example, to receive the kind of insults I am used to, they would be devastated. When they are old enough to start using the social media sites, such as Facebook and Instagram, that Meta owns, should I then pay extra in order that people can’t bully them, through impersonation? Conversely, if I can’t pay, should I just accept that bullying via impersonation is something they may have to endure?

This is by no means an abstract consideration. About twenty per cent of children aged 10-15 encounter online bullying in the UK, according to the Office for National Statistics. To you or me, this is twenty per cent too many. But the decision to introduce verified accounts suggests that Meta sees a sizeable market ripe for monetisation. It’s insidious, too, because where previously cyberbullying was seen as a problem for social media sites to police – not least because it has been directly linked to tragic instances of teen suicide – now one form of bullying, false impersonation, seems to have become a problem, much like the inconvenience of online advertising, for which users themselves must find a solution.

In this way, responsibility for the prevention of bullying via impersonation seems to be shifted slyly from the corporation to the individual. It becomes just another consumer choice. On Facebook, your bullying is now your fault. How meta.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in