Did you know that throughout the 19th century and well into the 20th it was considered a ‘biological impossibility’ for women to sustain the kind of abstract thought required for serious musical composition? Or that in the 1910s women in London could be compelled to sit separately from men in concert halls, sometimes even denied entry if not in academic dress? How about the fact that the Halle Orchestra summarily dismissed all its female members in 1920? Or that from 1952 to 1962 only eight works by women were performed at the Proms? For a bonus point, can you name the year – the decade, the century, even – in which the first opera by a woman was staged at the Vienna State Opera? (The answer is 2019.)

There’s nothing shouty about Quartet, the musicologist Leah Broad’s compelling group biography of four British female composers. The tone is restrained, but the quietly insistent patter of events, statistics, quotations and facts adds up by the end to a polemical roar.

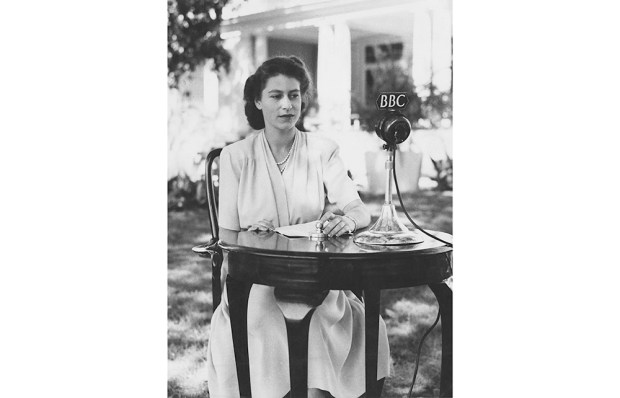

Broad’s ambitious debut interweaves the lives and careers of Ethel Smyth, Rebecca Clarke, Dorothy Howell and Doreen Carwithen into a single chronological narrative – a conscious attempt to avoid the isolating and exceptionalising of female composers that has historically led to their erasure, but also to situate them within a broader sweep of social and political history.

From the birth of Smyth in 1858 through to Carwithen’s death in 2003, we see the women intersect not just with each other but with the touchstones of religion, empire and emancipation, world fairs and world wars. We also follow all the more clearly the cycles of progress and retreat, and ground gained and lost, that underpin it all. This isn’t a history that moves from fringe to centre, exception to norm. It is variations on a theme, all adding up to a pretty damning portrait of an industry and an age.

‘You must cling to each rung of the ladder,’ Smyth counselled the young and despondent Howell, decades after she herself had started her own slippery ascent. Broad takes us through Smyth’s pioneering, no-holds-barred eruption into the turn-of-the-century boys’ club of composition, the throng including Clarke and Howell who followed, until – by the 1920s – ‘it was easy to programme an orchestral concert featuring only music by British women and have plenty of choice for pieces’.

But when the works proved substantial and challenging, critics of the 1930s would complain (and of no less august figures as Elisabeth Lutyens and Elizabeth Maconchy) that ‘no lipstick, silk stocking or saucily tilted hat adorns the music’; and in 1957 it was still acceptable for a newspaper to dismiss Ruth Gipps as a ‘housewife composer’, declaring that a woman could ‘no more be expected to conduct [Beethoven’s Ninth] than build a Great Boulder Dam’.

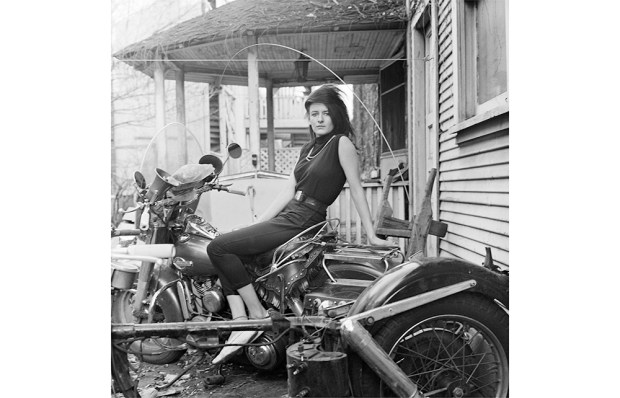

Faced with such resistance, Broad’s quartet of women responded in various ways. From Smyth’s de-sexing tweeds and desire to be an honorary man (her suffragette activism was a later stance) to the attractive and elegant Clarke, happy to play up to her femininity, to Howell’s fragile endurance, to Carwithen’s pragmatism, they did what was necessary to survive. It is striking that all four remained childless and two of them single, with Clarke and Carwithen only marrying late in life.

It’s in Carwithen – one of the first women accepted on to a scholarship programme to score films, and subsequently very successful in the field – that we see the risk that marriage represented played out most tellingly. By the time she died, we learn, ‘very few people knew that she had ever composed at all’. Her relationship with the composer William Alwyn consumed her – ‘she identified herself with him so much that at one point she began writing her notebooks as William’ – and pushed her work aside, as she focused on cementing his reputation and legacy. ‘Nobody,’ Broad writes, ‘would do the same for her.’

Even more poignant, perhaps, are the characters mentioned in passing – the women composers (or could-have-been composers) whose unfamiliar names are on every page: Dora Bright, who ‘had orchestral works performed in important venues’, Evangeline Livens, Alice Mary Smith, and Alwyn’s first wife, Olive Pull, who also gave up composing after her marriage. The weight of careers unfulfilled and music unheard is heavy, even against the vigorous counterthrust of Broad’s discoveries, and her succinct and urgent descriptions of repertoire.

‘How Four Women Changed the Musical World’ may be the book’s subtitle, but what we are meticulously shown here is that in many ways the situation remains stubbornly unchanged. Music by women still features in less than 8.2 per cent of concerts worldwide, and makes up less than 6 per cent of the soundtracks to the highest-grossing films. A woman today is more likely to lead a G7 nation than become the chief conductor of a major American orchestra.

Broad has done her bit – teaching us these composers’ names and uncovering many lost and neglected works in the course of her research. Now it’s the turn of publishers and ensembles to get them into the concert hall, and of all of us – free from chaperones and dress codes – to buy a ticket.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in