When news broke of Nicola Sturgeon’s resignation, the first reaction among Tory ministers was delight. For years, she had been one of their most formidable opponents and potent threats: perhaps the only politician capable of leading a Scottish independence campaign to victory. Without her, what would happen to the SNP? But then the elation faded. If nationalists’ votes are up for grabs, would they be more likely to go to Labour or the Tories? Sturgeon’s departure has consequences far beyond that of the SNP leadership. The UK’s whole political landscape could be about to change.

In her resignation statement at Bute House, Sturgeon said she believed more than ever in the cause of independence but had come to see herself as an obstacle, not an enabler. ‘We must reach across the divide in Scottish politics and my judgment now is that a new leader will be better able to do this,’ she said. ‘Someone about whom the mind of almost everyone in the country was not already made up – for better or worse. Someone who is not subject to quite the same polarised opinions, fair or unfair, as I now am.’

Plenty in her party agree. SNP sources likened her departure to that of the recent resignation of New Zealand premier Jacinda Ardern, hailing her as a selfless, progressive leader who decided to quit for the sake of her party when in fact she was facing problems she couldn’t escape. Her internal critics say the reality is Sturgeon was becoming mired in failure and scandal – and knew there would not be a winnable referendum any time soon. To pretend otherwise was a fiction that, in the end, even she was unable to maintain.

Her grip on her party has been sliding for some time. She spent months fighting claims that she tried to have Alex Salmond, her predecessor, imprisoned to remove him as a political threat. Every month seemed to bring a new headache: the growing rebellion over her gender-self ID act, the disclosure of loans from her husband to the SNP, the police investigation into a ‘missing’ £600,000 given ahead of a referendum campaign. She had plenty of scandals to flee.

Her strategy had been to buy time. Faced with a restive party and activist base, she called an independence referendum last year, something which she did not have the power to do. That ended in a court battle where the Scottish parliament was told it could not hold one without Westminster consent. While it gave SNP politicians a new reason to complain about Westminster frustrating the will of the Scottish people, it ultimately highlighted how few options she had to keep her troops happy.

Her declaration that the general election would be a de facto referendum riled SNP politicians in Westminster, who knew it would make their re-election far less likely, given that polls suggested a fall in support for independence. A successful plot to oust Sturgeon’s key ally Ian Blackford as Westminster leader was partly inspired by frustrations over her strategy. When Rishi Sunak decided to veto her Gender Recognition Reform Bill, he was on the sameside as Scottish public opinion: polls showed Scots were two-to-one against the policy. When a rapist claimed to be a woman and was sent to a women’s prison, it turned the debate into a political crisis that was, perhaps, not survivable.

Her domestic record was catching up with her, too. Having been leader for eight years, she had ample time to use all the levers of devolution to change a country in need of reform. But her domestic legacy makes for a grim read. ‘Let me be clear, I want to be judged on this,’ she said of the attainment gap in education in 2015. The gap is as wide as ever. The NHS in Scotland is about to ‘fall over’, according to leading medics, and the country has a deficit worth 12 per cent of GDP. Perhaps worst of all, drug deaths rose for seven of her eight years as leader and are worse than anywhere else in Europe.

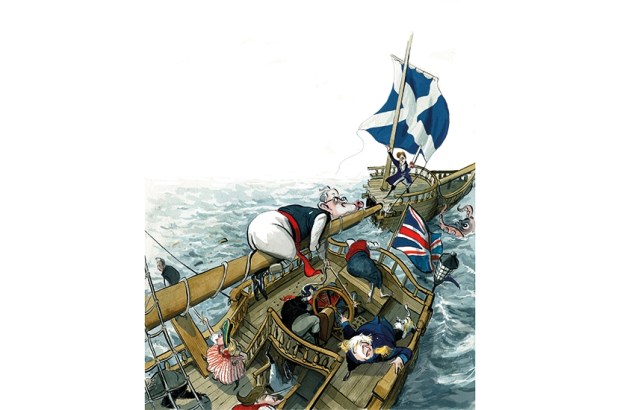

But as Sturgeon heads for a quieter life, politicians in Holyrood and Westminster are asking the same question: if she cannot lead Scotland to independence, who can? Unionists hope that without her the SNP will tear itself apart. Sturgeon said there will be those who feel ‘shocked, disappointed, perhaps even a bit angry’ with her, but said she is now giving them ‘tough love’. It could be very tough love indeed. The SNP was transformed by the 2014 independence referendum – in the general election the following year, the party went from six Westminster seats to winning 56 out of 59. That was when independence went from an abstraction to a palpable reality.

But if even Sturgeon seems to have given up, how many activists will stay? ‘Winning independence,’ she said in her resignation statement, ‘is a cause I am convinced is being won.’ But if she really does believe this, then why has she gone? The SNP has been already split on Sturgeon’s desire to put her party at the forefront of progressive campaigning politics. But her gender-ID plans were too much for many nationalists: from feminists such as Joanna Cherry MP to more conservative men. They have tended to gravitate to Alex Salmond’s Alba party, whose members were seen at a recent protest in Glasgow against Sturgeon’s self-ID bill, alongside unionists, feminist campaigners and family-values traditionalists. It was a sign that the anti-Sturgeon alliance was strengthening and expanding.

It was, of course, said at the time of his resignation that no one could lead the SNP after Salmond. Sturgeon was his protégée and after he stepped down she emerged with a potency even he never had: star power matched by few other politicians in Europe. Can the party repeat the trick? The SNP, she declared, is ‘full of talented individuals’. It is certainly full of politicians who have been asking what they would do if the ball came loose from the scrum.

One is Angus Robertson, a former West-minster SNP leader who lost his seat to the Scottish Tory leader Douglas Ross. Now back in Holyrood, he is the bookies’ favourite and the presumed successor among many MPs. Robertson is a genteel, articulate pro-EU nationalist who is a party old-timer. He would be viewed as a safe pair of hands.

He is followed closely behind by Kate Forbes, the Gaelic-speaking, Cambridge-educated finance minister who has been on maternity leave since July last year. Friends say that she could be persuaded, but only by her family. ‘She could run, or she could just as easily walk away,’ says one ally. ‘She’s not someone for whom there is nothing in her life other than politics.’ Others say that she has a new place outside Inverness which she and her husband are doing up and may have other priorities. She’s also a member of the Wee Free church, the daughter of missionaries, for whom faith comes before party – and this may make her hard for the socially liberal wing of her party to swallow. Could she end up being hounded, as Tim Farron was as Lib Dem leader, about her thoughts on sex and sin?

Joanna Cherry, a KC, is regarded by many on the opposition benches as one of the most effective performers, who has been a longstanding opponent of Sturgeon. She may run, but is unlikely to win given how many party members backed the gender recognition reform act.

Then there is Scottish health secretary Humza Yousaf. He’s ambitious and has been very much in the fray in recent months, while Forbes has been fairly absent during her maternity leave. But he can be abrupt, says one Scottish government source. ‘When he gets worked up, he makes Dominic Raab look like Buddha. All that might come out if he runs for leader.’

An outside bet could be the new SNP leader in Westminster, Stephen Flynn, who pushed out Ian Blackford. If his recent outings at PMQs are anything to go by, he could take on a more adversarial approach.

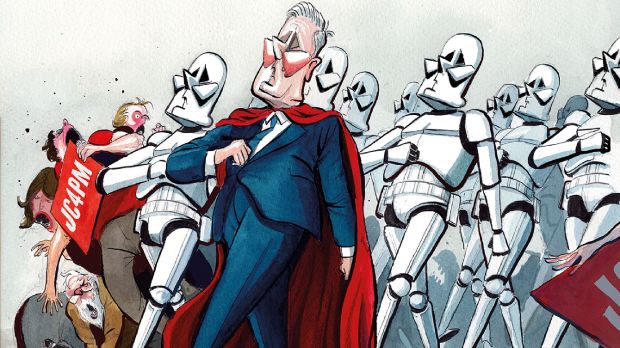

One SNP source says Sturgeon has dominated the party so much for so long that its apparatus has been built around her personally – with many of those in power owing their position to her patronage. ‘It’s like the old Soviet Union – the machine will pick a new leader not because they’re good but because they’ll keep the functionaries in their jobs,’ says one Holyrood source. ‘So they’ll choose an unofficial Sturgeon candidate, and try to keep it going. So there’s a real risk that she’ll go, but the party won’t renew.’

Should that come to pass, the big winner could be Scottish Labour. The party is resurgent under the 39-year-old Anas Sarwar, who became leader two years ago. There has been particular focus paid of late on candidate selection for Scottish target seats for the general election. Douglas Alexander, a former Scotland secretary, has been picked for the target seat of East Lothian. Keir Starmer’s team know that their biggest single chance in the general election is to win back the 40 seats they lost in 2015. The revival of Scottish Labour could be Starmer’s best route to a landslide victory.

This would be good news for unionists generally. If the nationalist movement splits, Scots may peel away from nationalism altogether. But it could be bad news for Tories. ‘As a unionist, I’m delighted,’ said one Scottish Tory MP. ‘But as a Conservative, it’s a nightmare.’ Others in government are simply delighted that their toughest opponent is on the way out.

But the celebrations that could be heard on the day of Salmond’s resignation were horribly premature. She may now go for a job in world politics, one that capitalises on her self-styled image as an ‘optimist’ who pushed the gender recognition issue perhaps harder than her country could bear. She has said she’ll stay on the scene, campaigning. It would be wishful thinking, right now, for unionists to declare that her cause is now buried. As Sturgeon ends her front-bench political career, she has paved the way for a shake-up of British politics that could decide the next party of government – and the future of the Union.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in