The great country singer George Jones was famed not just for his voice, but also for his drinking. Once, deprived of the car keys, he drove his lawnmower to the nearest bar. In the very good Paramount+ drama about Jones and Tammy Wynette – entitled George and Tammy, so there’s no excuse for forgetting – Michael Shannon, playing Jones, is asked time and time again why he keeps on making such a mess of his life and his career. ‘That’s what the people want from me,’ he shrugs in reply.

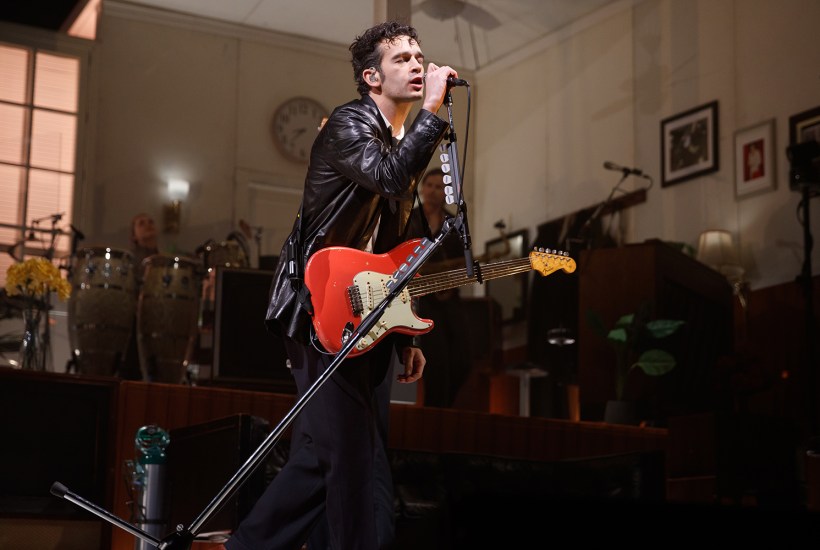

That came to mind watching the 1975’s return to British arenas, in a tour grandiosely and amusingly billed as ‘In Show and In Concert – The 1975 At Their Very Best’. Matty Healy, their 33-year-old frontman, is the 1975’s George Jones – he’s gone through rehab for heroin, he’s broken down on stage, he’s had a habit of getting himself into the kind of situations from which it can be hard for pop stars to extricate their careers without damage.

But his problems have, if anything, only deepened the bond between Healy and his fans (and, perhaps, convinced a few of the critics who were snooty at first about a mere pop group to take him seriously). But what to do when you’ve kicked the heroin, made your most focused album yet and still some people come to your gigs expecting you to screw up or be screwed up?

The 1975’s answer was to make breaking down the point of the first half of the show. The stage was set as an apartment: the band members entered through a ‘front door’ at the back of the stage; the supplementary musicians and drummer George Daniel were positioned in individual ‘rooms’ upstage, the front three – Healy, guitarist Adam Hann (no relation) and bassist Ross MacDonald – in the downstage ‘living room’, bedecked with standing lamps and soft furnishings.

That first half consisted largely of the newest album – Being Funny in a Foreign Language – as Healy gradually acted out his own disintegration. On the opening night in the United States it was sufficiently convincing that when the first half ended with Healy eating raw steak, then doing press-ups, social media was abuzz with posts along the lines of ‘omg someone has to help Matty!’

A testament to the 1975’s current starpower is that the gap between the two halves was filled not with piped music, but with Taylor Swift popping on entirely unexpectedly to sing acoustic versions of her own ‘Anti-Hero’ and their song ‘The City’, before she was replaced again by the band to run through an hour of greatest hits (although, in this atomised musical world, few of the ‘hits’ that 20,000 or so people sang along to – ‘Sex’, ‘Somebody Else’, ‘The Sound’, ‘Chocolate’ – registered in any great way in the charts).

Days later, I was still thinking about what a brilliant show it had been, even if the initial conceit is just Pink Floyd’s The Wall, but without Roger Waters hectoring you about Israel every five minutes. This, I think, is the first time, since they reached arenas, that the 1975 have actually got the set right. The new album is concise and melodic, free of self-indulgence, which meant it worked when played in full. And they have largely excised the ambient interludes that they clearly loved to play, but which had a tendency to stop their momentum. This show was all about velocity – wall-to-wall bangers, brilliantly paced and fantastically performed.

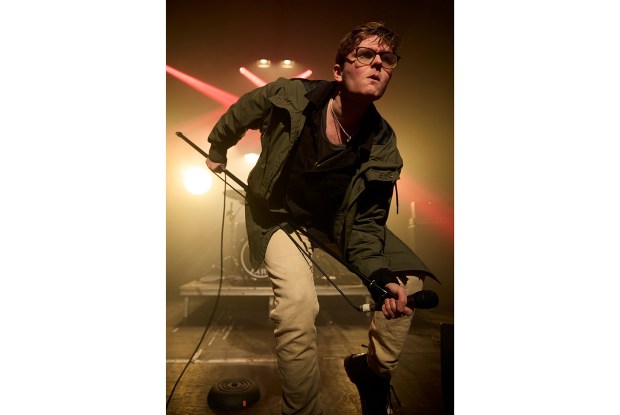

When the great Americana singer/songwriter Lucinda Williams took to the stage at the Barbican, she had to be helped to the microphone, and a stool was behind her in case required. Williams, who is 69, had a stroke in November 2020. Whereas the 1975 – their music, their fans, their urgency – are all about now, there was an awful lot of then about watching her play (this was the first time I have ever been startled by the number of walking sticks and canes in the audience at a rock show).

Her voice remains, largely, a thing of wonder – woody but fresh and expressive. She’s not afraid to set emotions in the simplest terms: ‘Stolen Moments’, written for the late Tom Petty, boiled down to little more than her saying: ‘I think about you.’ But the simplicity comes from the collision with profundity; when she played her third song about someone she loved who had died, she stopped to apologise for the profusion of morbidity. The presence of mortality, and both our and her awareness of her fragility, lent the evening a deep emotional power.

Younger artists and younger fans might glamourise self-destruction, but it’s the older artists and their audience who truly understand that in the midst of life lies death.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in