‘Spain must be much more interesting than Liverpool,’ decided the 12-year-old Archer M. Huntington after buying a book on Spanish gypsies in the port city. The family of American railroad magnate Collis P. Huntington had just docked at the start of an 1882 European tour that would introduce Archer to the National Gallery and the Louvre. ‘I knew nothing about pictures,’ he later admitted, ‘but I knew instinctively that I was in a new world.’

It was the Hispanic world to which he was most attracted, and he hatched a plan to create a museum devoted to its study. His preparations were thorough; he learned Arabic as well as Spanish before setting off in 1892 on the first of three explorations of the Iberian Peninsula. He took a principled approach to art collecting: ‘To Spain I do not go as a plunderer,’ he vowed. ‘I will get my pictures outside [the country].’ By 1904 he had got enough to found the Hispanic Society of America, which opened its doors in Upper Manhattan four years later.

Given the British love of the Costa del Sol, we’re shamefully ignorant of Spanish culture, feeling more at home with French and Italian – an imbalance contemporary British philanthropist Jonathan Ruffer has helped to correct with the opening in 2021 of a Spanish Gallery in Bishop Auckland, whose castle boasts a collection of paintings by Zurbaran. Now the Royal Academy’s loan exhibition of treasures from the Hispanic Society Museum & Library is offering Brits a crash course in all things Hispanic, starting with geometric-patterned earthenware vessels decorated by the Bell Beaker people of the third millennium BC and ending with sun-drenched Valencia beach scenes painted by Joaquin Sorolla in the 1900s.

A mix of Celtic, Islamic, Jewish and Christian with Amerindian, African and Asian influences via the Manila-to-Acapulco trade route, Hispanic culture is the ultimate melting pot, but through it all runs a sense of Spanish pride. There are no more grandiose knobs and knockers than those adorned with dragons, wolves and dogs attached to the doors of 16th-century Castilian mansions – Spanish nobles believed in making an entrance – nor more lavishly illuminated ‘Letters Patent of Nobility’. Ancestral pride shows a less noble side in the 18th-century fashion for Mexican casta paintings illustrating different racial mixes: ‘Mestizo and Indian produce Coyote’, reads the inscription on an example by Juan Rodriguez Juarez.

The Latin-American galleries are the most fascinating. ‘A World Map’ (1526) by Giovanni Vespucci, nephew of Amerigo, draws a blank beyond America’s eastern seaboard and an illustration of ‘The Silver Mines at Potosi’ (c.1585) shows them going full tilt 40 years after the Spanish struck silver on Bolivia’s Cerro Rico. The quality of the local silverwork is dazzlingly illustrated in a tray embossed with birds, lions and chinchillas that ended up as the centrepiece of Queen Charlotte’s table, though only after she’d had it regilded. It wasn’t glitzy enough.

A fine example of another viceregal speciality, Mexican enconchado painting inlaid with mother of pearl, is Nicolas de Correa’s vivid ‘Wedding Feast at Cana’ (1696) in which you can read the reluctance on Christ’s face – ‘Must I, Mum?’ – and the panic in the kitchen, while a set of exquisitely gruesome polychrome carvings of the ‘Four Fates of Man after death’ testifies to the extraordinary skill of 18th-century Quito sculptor Manuel Chili ‘Caspicara’. By comparison, apart from a lovely Zurbaran, ‘St Emerentiana’ (c.1635-40) in a gorgeous frock, the sacred art from mainland Spain is run-of-the-mill, though the gilded breasts of Juan de Juni’s polychrome ‘Mary Magdalene’ (c.1545) stand out. There are a couple of unexceptional El Grecos – Bishop Auckland’s Spanish Gallery pipped the RA to the loan of the Hispanic Society’s beautiful ‘Holy Family’ (1585) – and two masterpieces by Goya: a portrait of fellow bullfight afficionado ‘Pedro Mocarte’ (c.1805), a study in disappointed middle age, and the famous full-length of feisty widow, ‘The Duchess of Alba’ (1797), pointing down with a finger at the words ‘Solo Goya’ inscribed in the sand at her twinkle-toed feet. But the show is stolen by a breathtakingly informal ‘Portrait of a Girl’ (c.1638-42), possibly his granddaughter, by Velazquez. It would have thrilled Manet.

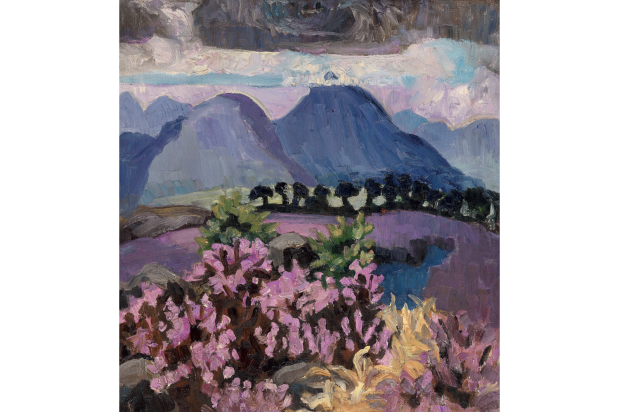

In the 1900s Huntington began collecting paintings by contemporary Spanish artists such as Sorolla, Ignacio Zuloaga and Hermenegildo Anglada Camarasa. In 1911 he commissioned Sorolla to decorate a gallery with a 277ft mural illustrating the regions, customs and costumes of Spain, a marathon exercise in ‘costumbrismo’ that took the artist the best part of ten years, and killed him. Scanning the 25ft sketch of one section in the show’s final room, you can see why. There are no Picassos in the collection, Huntington having eventually come to the conclusion that contemporary art was ‘a dealer’s affair and not… one for museums’. He had a point.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in