In a recent column, I explained why Emily Oster’s amnesty call for lockdown and vaccine zealots provoked white-hot rage. A poll conducted on 2 to 4 November found a 39-to-35 majority US opposition to amnesty. The sense of justice, fairness and equity is deeply ingrained in human beings. The victims of casual cruelty, capricious public health diktats and enforcement brutality are owed justice. But what type of justice?

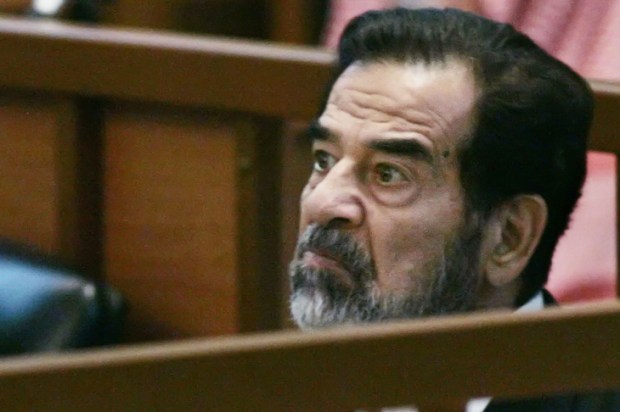

It might be helpful to look at examples from international criminal justice. In 1992, tyrants could commit atrocities against their own people inside sovereign borders with impunity. Today, there is no guarantee of prosecution and accountability. But not a single brutish ruler can be confident of lifetime escape from international justice: the certainty of impunity is gone. The creation of the International Criminal Court was the institutional embodiment of the transformation. Yet, despite some successes the hopes of the ICC remain mostly unrealised. An initiative meant to protect vulnerable people from brutal national rulers has been subverted into an instrument of powerful against vulnerable countries. In 2013, reflecting the depth of anger at ICC charges only against Africans, Ethiopia’s prime minister accused the ICC of ‘hunting’ Africans. The likelihood of officials of major powers being held to account for criminal conduct is greatly diminished by the reality that the UN Security Council is dominated by the five veto-wielding permanent members. This makes the UN as impotent against Putin’s aggression in Ukraine as against Bush and Blair for the Iraq war. Former colonies also weigh present rhetoric on human rights against the colonial record of the leading Western powers. Nuremberg and Tokyo too were instances of victors’ justice even though, by historical standards, both gave defeated leaders the opportunity to defend their actions in a court of law instead of being dispatched for summary execution.

The logics of peace and justice can be contradictory. Peace is forward-looking, problem-solving and integrative, requiring reconciliation between past enemies within an all-inclusive community. Justice is backward-looking, finger-pointing and retributive, requiring trial and punishment of the perpetrators of past crimes. ICC indictments have sometimes jeopardised the prospects of peace in African conflicts. Leaders have less reason to give up power and opposition rebel groups are reluctant to enter into negotiations with indicted war criminals. Ian Paisley Jr. holds that if the ICC had existed during the Northern Ireland peace process, its intervention ‘would have driven old enemies even further apart in recrimination and hostility, hobbling the chance for peace’.

Criminal justice can exclude options of alternative modes of healing and restitution and solidify the social cleavages that led to the crimes of genocide and ethnic cleansing. A better assurance of protection for people is peaceful resolution of conflicts by political efforts, followed by the establishment of institutions of good governance. The ‘punitive and retributive focus of trials’ limits the ability to move to post-conflict reconciliation by alternative means of ‘ensuring accountability, deterring repetition and reconciling societies’, write Richard Goldstone and Adam Smith. The purely juridical approach to justice can trap and suspend communities in the prism of past hatreds. Truth commissions, a halfway house between victors’ justice and collective amnesia, take a victim-centred approach. In Chile and South Africa, they helped to establish the historical record and contributed to memorialising defining epochs in the national histories of both countries.

The South African case is especially instructive because the apartheid state was such an international cause célèbre. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission became a celebrated case of the genre. The process was at least as important as the final product. South Africa opted for a statutory body set up by parliament, not a presidential commission. The TRC had subpoena powers that carried the carrot of full amnesty and the stick of criminal prosecution. It held public hearings under shady trees in villages as well as in churches (with the attendant symbolism of repentance and forgiveness) that were televised to a global audience. For 30 months, the TRC was the national story: compelling, gripping, poignant – and cathartic. Rwanda’s version of transitional justice operated through the local gacaca system of people’s courts whose overriding goal was not to determine guilt but restore harmony and social order. Mozambique offers equally successful examples of communal healing techniques. All three cases represented deliberate efforts through social and political channels to escape cycles of retributive violence coming out of decades of tumultuous political conflicts congealed around communal identity. Their record of bringing closure to legacies of systematic savagery in deeply conflicted societies is superior to that of institutions of criminal justice.

However, justice has many more roles to play beyond simply bringing wrongdoers to account: acknowledging the suffering of victims, educating the public and deterring future atrocities. It’s not possible to secure lasting peace without bringing criminal wrongdoers to account. Criminal trials establish individual responsibility for the crimes and thereby negate the notion of collective guilt that can otherwise impede intercommunal reconciliation. Allied and Axis powers are at peace not just despite the Nuremberg and Tokyo tribunals, but also because justice cleared the path to reconciliation. The core point is that these are not primarily and solely legal decisions but profoundly political choices with complex trade-offs. The ethic of conviction imposes obligations to prosecute people for their past criminal misdeeds. The ethic of responsibility imposes the countervailing requirement to judge the wisdom of alternative courses of action on their consequences for social harmony and political stability today and in future.

Applying all this to Covid policies, neither a Senate inquiry nor a royal commission is likely to prove ‘fit for purpose’. The duration of the emergency measures, the scale of damage and the depth of trauma is much too great for that.

Families were torn apart, friendships broken, Mum and Dad businesses shuttered and large segments of the population were stigmatised and banished from society as germ-carrying, unclean beings. We need both criminal accountability for the chief health officers, heads of governments, health ministers, and police commissioners; and a TRC for the bigger cohort of high profile ‘health influencers’ of epidemiologists and medical experts, public intellectuals and media commentators who gave full rein to their inner bullies to shame, vilify, ostracise and otherwise traumatise all who dared to think for themselves and refused to go along in order to get along.

The nation needs healing.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in