One by one, life’s harmless little pleasures are outlawed by an overweening, repressive government. The Online Safety Bill has been doctored by MPs to stop people making use of ‘deep fakes’. This means that my enjoyable pursuit of Photoshopping the heads of politicians I dislike onto the naked, writhing bodies of Russian porn stars and sending the resultant images, anonymously, on Christmas cards to members of the local clergy is now illegal. In future I will have to get the consent of each politician before I send them off to the vicar. I had a great one recently of Liz Truss going at it like the clappers with Mark Drakeford, the First Minister for Wales. It seems to me harmless fun and if discovered could surely only improve Mr Drake-ford’s image and poll ratings, although he does not seem to me the kind of chap who could take a joke. Anyway – all gone. I wonder what they will ban next?

Quite possibly it will be fairy stories. A recent opinion poll has revealed that they terrify people under the age of 30, who consider them horribly inappropriate for children. Some 77 per cent of those surveyed believed – with a crushing inevitability – that they were ‘sexist’. Nine in ten said they are old-fashioned and outdated.

I suppose it is hard to argue against the allegation that many fairy stories are indeed what would be called ‘sexist’ now, in that they portray men and women in a slightly different manner and often occupying what we might call ‘traditional’ roles. (It rather reminds of that old joke. Why are children’s storybook adventure heroes always men? Answer: to make them more believable.)

I do find it all a little depressing, though, for it is simply more evidence that millennials and even Generation Zers wish to abolish everything from history and everything we have learned from it. Some of these fairy tales date back 6,000 years – the Neolithic period in Europe and around about the time we first domesticated horses. That they have lasted, often scarcely changed, over the intervening millennia seems to me evidence that they contain certain immutable truths, applicable to all, regardless of whether we were chasing the last handful of mammoths or attempting to split the atom. If we think of them as largely Victorian in origin, then that is primarily the responsibility of the Brothers Grimm, who collated these ancient stories and made them popular again for young children via the newish technology of mass printing. The point, though, is that every one of these fabulous stories was created in order to inculcate some sort of moral or practical lesson.

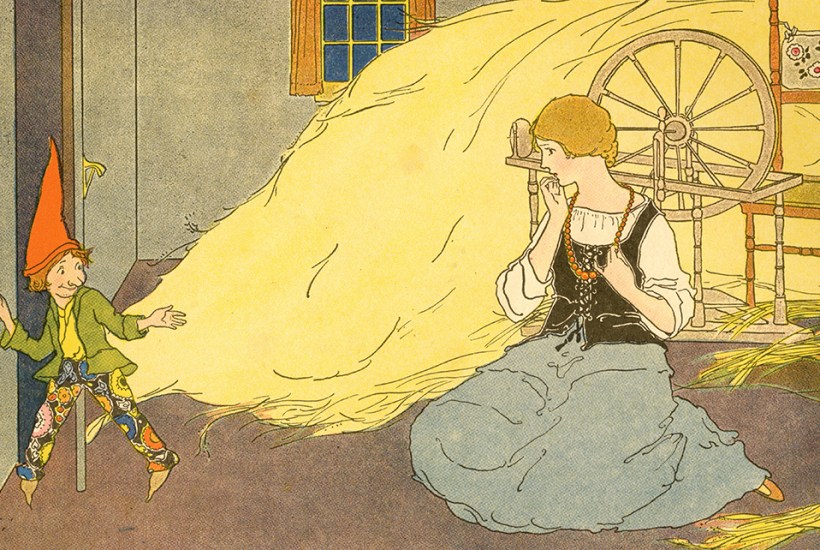

The legend of Rumpelstiltskin is one of the very oldest and is largely a lecture on the importance of title, of naming something – as well as a warning not to brag too much. Rumpelstiltskin was a rather unpleasant imp who, for a price, wove straw into gold for the daughter of a local miller, who had unwisely claimed his hapless offspring had this ability in order to big himself up to the local king. She was no more capable of doing this than you or I, but Rumpelstiltskin helped her out, at the cost of a necklace, then a ring, and finally her own firstborn. Distraught, she was told she could escape from this last tariff only if she discovered the name of the imp, which she did when she heard him injudiciously singing it out loud in a nearby forest. And so we have the enduring and useful ‘Rumpelstiltskin Principle’, as used in modern psychology: to know the name of something, or to give a name to something, is to hold a sort of power over it, the power of title (as in the word ‘entitlement’).

All of these tales contain helpful warnings to the young. The Three Little Piggies yarn was about the necessity of working hard and not skimping, especially concerning building materials, while The Sleeping Beauty suggested the benefits of deferred gratification and waiting for love. Goldilocks taught children to respect the property and privacy of others, particularly if they are bears, while Jack and the Beanstalk enjoined children to make the best of opportunities which come their way.

The problem with the current generation, then, is twofold. First, they have been schooled to see all texts through only the very narrowest of prisms – according to the complaints of victimhood from anybody with a ‘protected characteristic’. These fairy stories thus become simply conduits for grievance and resentment – the king’s treatment of the miller’s daughter and the fact that she is anxious to marry into royalty. The real point of the story is entirely lost, because today such stories are read with blinkers on. I remember when one of my sons was reading John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men and his essay question was about the sexism inherent in Curley’s relationship with his squeeze, Candy – the point of the little fable entirely lost on this new audience. The same occurred later with a reading of Othello. Such a suffocatingly narrow approach to literature.

The second problem is that we have a generation for whom history means absolutely nothing: it is a dark and dismal place where people behaved terribly badly to one another and may even, on occasion, have misgendered people.

We need take no lessons from history, then – better to abolish it. History will only inculcate in our children the outdated and frankly obnoxious stereotypes which we have done so much to banish. And so 6,000 years comes to a rather abrupt end.

In their place, the current generation give us their own fairy stories about everybody being equal in everything and men happily turning into women – a complete inversion of the old fairy stories in which the actors in each were obviously fictitious but the moral real and immutable. In the current fairy stories the people are real enough, but the lessons wholly fictitious.

The post In defence of fairy tales appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in