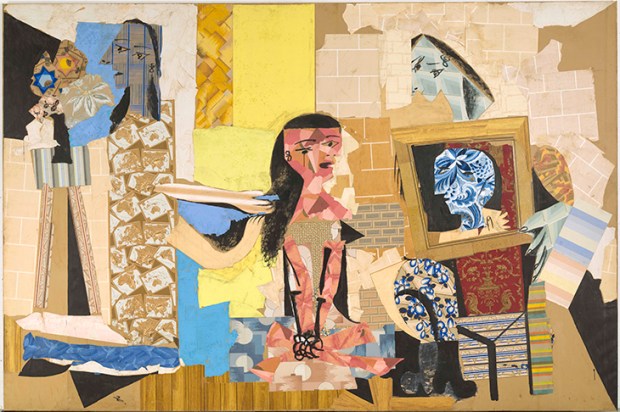

The catalogue to Making Modernism opens with an acknowledgment from the Royal Academy’s first female president, Rebecca Salter, that in the past it has overlooked women artists. To compensate, it has bundled seven – four headliners and three of their lesser-known contemporaries – into this one show.

Excluded from official art schools and reliant on private tuition and ‘ladies’ academies’, these seven women escaped the feminine curse of the three ‘Ks’ – Kinder, Küche, Kirche (children, kitchen and church) – to forge independent careers in Germany before the first world war.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in