It is hard to imagine why anyone should want to write one, but if there has to be a history of the whole world then Simon Sebag-Montefiore must be as good a candidate to write it as anyone. He would seem to have read pretty well everything that has ever been written, visited everywhere of historical interest on the planet and enjoyed – thanks to Covid and lockdown – the time to write the one book that he has always had in his sights.

The only history we ‘adore’, Chairman Mao reckoned (and he ought to know), is the history of wars, and in The World: A Family History Sebag-Montefiore has taken the message to heart. There may well be the odd family in which brothers do not routinely strangle each other, children do not blind their parents or parents wipe out their heirs; there may even be families who’d rather build a loft extension than a tower of severed heads, but if there are any such there’s not much sign of them here.

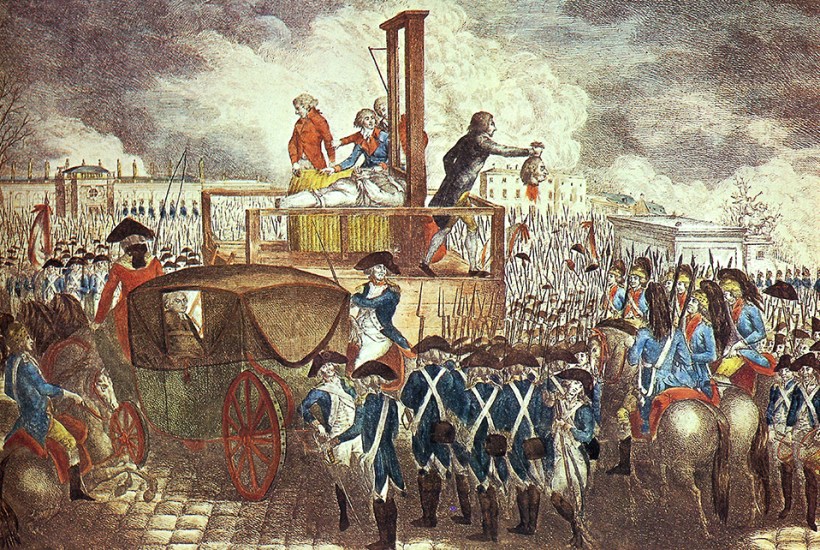

‘Family,’ Sebag-Montefiore writes with Mao in mind, has always been ‘at the mercy of power’, and this is a book about power, and only then about the great dynasties that wielded it. There is the occasional oasis of calm and sanity among the mayhem, but the author’s ‘World’ is unashamedly the world of Game of Thrones, one of rising and falling kingdoms and empires, of battles, sieges, torture, madness, rapine and – a disturbing speciality of his – executions of an ever more obscene kind.

‘House Alara’ (Nubian Kush), ‘House Tilgeth-Pilaser’ (Assyria) – even the chapter headings are early nods in the direction of Game of Thrones, and the only surprise in a history that runs from the first murderous hominids down to Putin, Kim and Assad is that ‘House Lannister’ or ‘Baratheon’ are missing. For any reader with the stomach for bloodshed and megalomanic ambition, for anyone with a taste for Ptolemaic depravities or who would simply like to spend some quality time with China’s imperial eunuchs, then Sebag-Montefiore’s ‘World’ – the world according to Alexander the Great and Attila and Genghis and Tamerlane and a countless host of other killers ancient and modern – will deliver it and more in spades.

The ‘World Game’, as he calls it, had its compensations for men, of course; but for women – in spite of the author’s best efforts to unearth anyone who ‘showed defiant agency in the face of male cruelty’ (just what the Tatars called it) – it was a black, black picture. There were certainly women from the Nile and the Tiber to the Asian steppes who showed a terrifying degree of agency, and there were women from the earliest times who exercised real power. But for the tens of thousands who fill these pages in the roles of wives, concubines, slaves and victims, the best to be hoped for – if a rival didn’t poison you first or Tamerlane’s hordes find you – might well be a quick killing and sacrificial burial on your master’s death.

If it might seem strange that an author so sensitive to the concerns of contemporary history writing should go in for anything so old-fashioned as dynastic history, the two things turn out to be surprisingly well aligned. At the heart of this book are all those empires – Egyptian, Nubian, Assyrian, Chinese, Arab, Mongol, Indian, Inca – that for a great part of human history fought for the world; and if the global sweep of the narrative rams home anything it is that an Anglo- or Euro-centric view of the past will teach us very little about our global heritage.

Indeed, perhaps the author’s major achievement is to make us see the world through a different lens – to make the unfamiliar familiar and, more important, the familiar unfamiliar. The British and the other European colonial powers would have their day; yet long before they made history and much of the planet their own, before the East India Company or the Dutch VOC ‘opened up the east’ or the Atlantic slave trade began, Chinese fleets were crossing the Indian Ocean and Arab caravans were transporting slaves – six million of them between the 11th and 16th centuries – in a world already intricately connected by commerce, politics, religions, slavery and (that most bizarre index of ‘species success’) pandemics.

Europe would more than catch up, in other ways too – the persecution of Jews is a running theme of the book, and nothing is more soberly powerful than the section on the Holocaust – but it is that other world that this book brings most vividly, almost feverishly, to life. It is a huge subject; but then this is a doorstopper of a book, running to a numbing 1,262-plus pages.

And therein lies the rub. It was not for nothing that Gulliver came across a room devoted to a mechanised history of everything in the Lagado Academy, because there is ultimately something gloriously, self-defeatingly Laputan in a book of this scale and ambition. While there is hardly a dull paragraph here, there is surely a limit to what readers can take, and 1,000-plus pages of self-indulgent storytelling might just have reached it. I had a letter once from a very charming and alert lady in her mid- nineties who was reading a book I had written on Captain Scott. She said how much she was enjoying it, and that she had got to page two hundred and something, but would I mind very much if she didn’t finish it because, as she put it, she really didn’t want it to be the last book she ever read. It would be a shame if readers in their early twenties, eyeing the mountain that still lay ahead of them, should end up sending Sebag-Montefiore the same sort of apology.

The post The history of the world in bloodshed and megalomania appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in