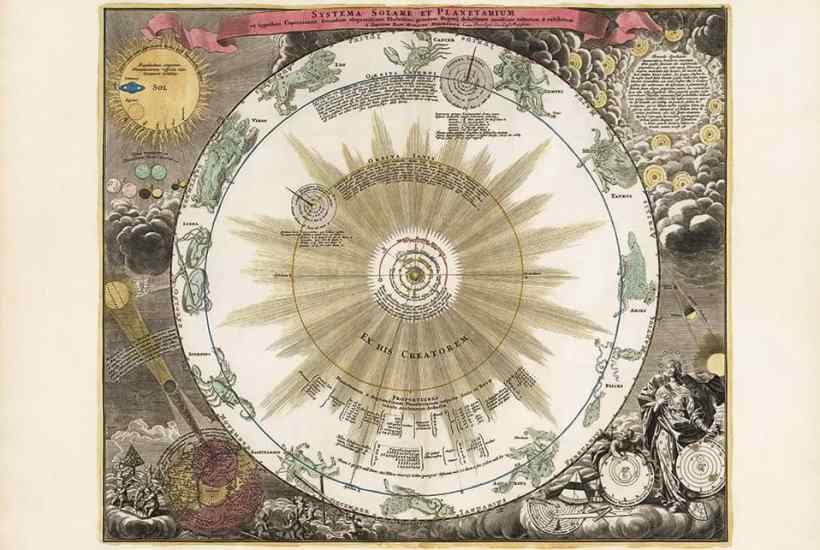

It seems something of a disservice to a work of this seriousness to say how beautiful it is, but that is what will first strike the reader. Open this book and if you can prise yourself away from its wonderful marbled end papers, with their swirls and drifts of deepest blue, brilliant flashes of rusty orange, rivulets of ochre, inky spheres and floating masses of fiery red, you will find yourself taken back to the Enlightenment world of Johann Gabriel Doppelmayr’s Celestial Atlasand an age in which Europe’s polymaths were as interested in the discoveries of science as they were...

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in