Three years ago, I killed several thousand people over the course of a single weekend. Late into the night, I ran around butchering everyone I saw, until by the end I didn’t even feel anything any more. Just methodically powering through it all, through the wet sounds of splattering heads, bodies crumpling, shiny slicks of blood.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

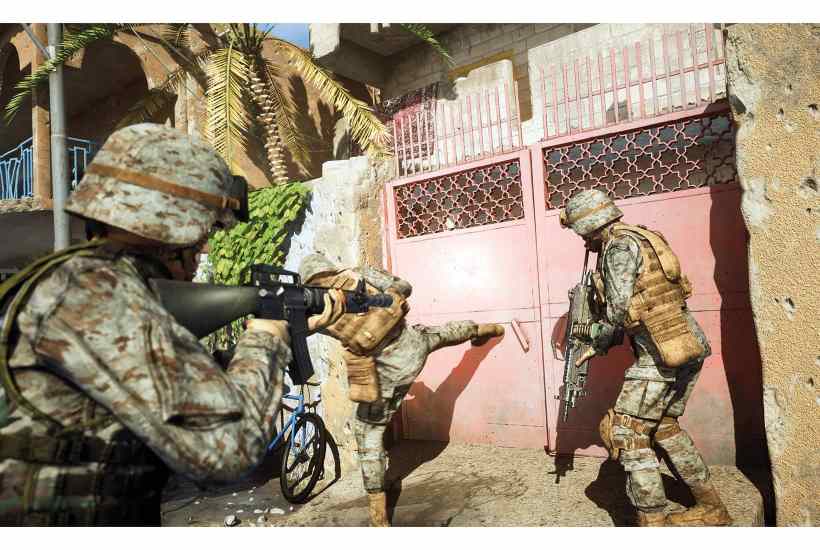

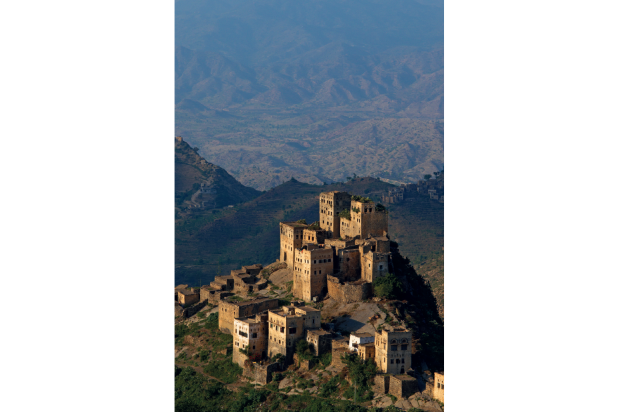

War Games is at the Imperial Museum London until 28 May 2023.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in