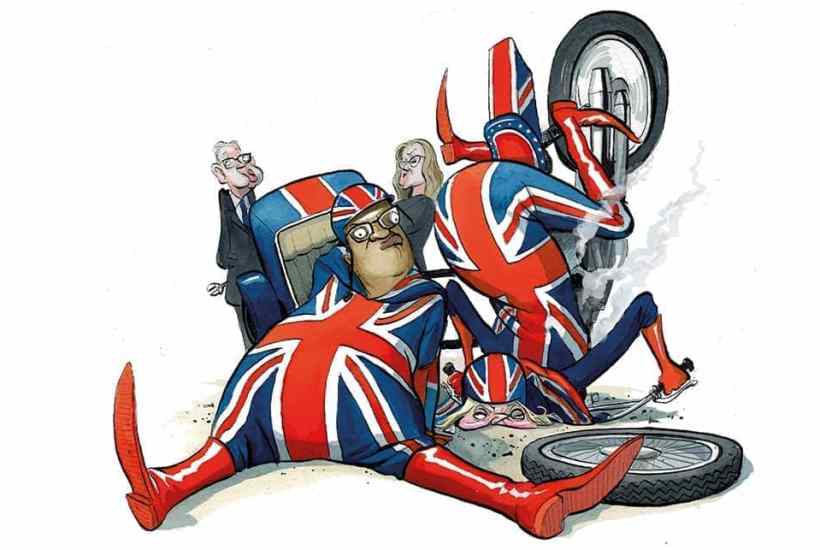

Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng wanted to shake things up. They were radicals in a hurry, keen to show that Britain was under new economic management. Theirs would be an unapologetic pro-growth agenda: no more genuflection in front of failed orthodoxies, no more being paralysed by fear or criticism. As a sign of this, they abolished the 45p tax rate for the highest earners: a move that many Tories longed to make, but did not dare. It seemed Truss and Kwarteng would leap in where other Conservatives feared to tread.

This lasted just ten days. As the tax plan was reversed and No. 10 licked its wounds, there was much talk of how scrapping the 45p rate didn’t really matter that much – just a £2 billion measure in a £100 billion budget, it had become a distraction and wasn’t the most economically important part of the package. But just as Truss and Kwarteng wanted to scrap it because it was totemic, so their retreat is totemic.

These revolutionaries have been forced to acknowledge the power of those political forces they had derided. They fought the law of politics and the law won. They have had to accept why five Conservative chancellors didn’t return the top rate to 40p where it was under Gordon Brown, and why George Osborne only cut it to 45p from 50p. Brown knew the new rate would raise hardly any tax, but he intended it as a political booby trap – any Tory who tried to dismantle it would be ensnared. So it has proven.

The party conference in Birmingham marked the dramatic end of the first phase of the Truss government. From now on, whenever her administration announces a radical policy, there will be a question over whether it will actually happen. ‘Every time they send us out to defend something controversial, we’ll be asking: why should we?’ says one MP. ‘If they backtrack, it’s egg on all of our faces.’

In private, Truss says she has not given up on radicalism – and regards the fight over her mini-Budget as a minor skirmish in a big war. Those who saw her behind the scenes in Birmingham were astonished at her cheerfulness. She agrees with her Home Secretary that the policy wasn’t wrong. Rather, she blames the problem on a lack of pitch-rolling – and accepts that she failed to make the case. The City wasn’t prepared for the mini-Budget and once the markets began to react badly, the situation became untenable. Even her cabinet were blindsided by the 45p tax rate removal.

Those who share Truss’s worldview argue that their enemies – and even the markets –are politically motivated. The market, they claim, is suffering from groupthink; it is part of the low-risk, low-growth consensus that has dominated since 2008 and that attitude informed its reaction to the Budget-by-any-other-name. But the brutal truth is that, whatever you think of the market’s reasoning, the market creates reality: it dictates the interest rate at which the government can borrow.

David Cameron used to U-turn regularly. Veteran Tories joked that they had never known a prime minister who got into more scrapes or who was better at getting out of them. He could manoeuvre out of such situations because he travelled light ideologically. Truss does not. She has a deeply held worldview, developed over the past 20-odd years. A decade in government has not dimmed her radicalism. Indeed, since entering No. 10 she has been busy pushing ideas that previously her bosses regarded as too bold. She’ll drive forward the supply-side, red-tape-cutting measures she has promised.

Truss faces a new problem, however. Tory MPs will believe that a principle has been established: this Iron Lady is easily bendable and backs down if enough pressure is applied. This will limit her ability to push through difficult reforms, to say nothing of the coming public sector pay settlements. Anything controversial will be met with resistance. Faced with near-cataclysmic poll ratings, Tories will be very wary of doing anything that might go down badly in their own seats (on current polls, about half of Tory MPs will be looking for work come 2024).

This is another break on Truss’s would-be radicalism – so many of her MPs think there’s no time for radical reform. With an election in 18 months and a Tory collapse in prospect, even Conservative MPs with 10,000-plus majorities start putting their personal survival above all else. If they wouldn’t pass planning reform under Boris Johnson because they were worried about their constituencies, it is hard to imagine them agreeing to even minor liberalisations now when even those in normally safe seats feel endangered.

A radical leader is therefore confronted with a deeply cautious, shell-shocked party. Even Jacob Rees-Mogg acknowledged this week that, as a rule, reforms cannot proceed without public consent. As one Tory MP puts it: ‘Two weeks ago I thought I would lose my seat to the Lib Dems. Now I think I’ll lose it to Labour.’ I know of one Tory with a 19,000 majority who is drawing up a battle plan to save his seat. The big obstacle Truss faces is not from the emboldened left but the terrified right.

With the polls pointing to defeat, people start to position themselves for what might happen afterwards. Suella Braverman, the Home Secretary who stood for the leadership last time, is already setting out her own distinctive stall on immigration: she wants to use the work permit system to revive the Cameron-era target of reducing immigration to the ‘tens of thousands’. She tells this magazine on p. 14 that she wants lower migration to mean higher pay. Hardly a sign that a new, more pro-growth immigration system is coming.

Braverman justifies her policy by referencing the 2019 Tory manifesto pledge to lower immigration. It’s an interesting tactic. By signalling that she is a break with what went before, Truss has called into question the basis on which she is making these reforms. On whose authority does she act? Johnson put together the Red Wall coalition. Many of Truss’s reforms were not even explicitly spelt out during her leadership bid. This riles allies of Johnson, who are keen to protect his legacy.

The Truss approach to party management has made this problem worse. Rather than obeying Winston Churchill’s dictum – in victory, magnanimity – she took the view that to the victor goes the spoils. She filled her government with loyalists. It’s not that she just exiled critics: she exiled those who had stayed silent. Grant Shapps said little in the leadership contest after he had backed Rishi Sunak, and he never attacked Truss. Yet he was still dropped from the cabinet, and now deploys his communication and organisation skills to destabilise the Prime Minister.

Or take Michael Gove, who turned out to be an unlikely star of the Tory conference. His relationship with Truss is – to put it mildly– difficult. Once united as school reformers, they then fell out. She increasingly came to see him as a nannyish control-freak whose influence extended too far. Her decision to shut him out was more personal than political. She could have made him health secretary and told him to stop the NHS from falling over this winter (the issue which remains the biggest risk to the Tories). If he had succeeded, Truss would have benefitted. If he had failed, his career would have been over. By exiling him, she left him free to campaign for his style of Conservatism – which is very different from hers.

Truss may not get the luxury of doing battle with the left, given her issues with party management. What she needs most is a good chief whip, but Wendy Morton, her choice for the job, is not having the easiest time: two rebellions in the first three days of party conference is something of a record. Truss ought to have given the job to Thérèse Coffey, one of her best friends. Having been in cabinet and since she gets on with everyone, Coffey would have found it easier to deal with the Michael Goves of this world, and could have fed back some candid advice to the Prime Minister. She would have been a two-way valve between the leader and the party.

Yet any chief whip would face a mighty difficult job, because there is a philosophical battle going on in the Tory party. Many former ministers regard Truss as a libertarian interloper, not really a proper conservative – more of a Manchester Liberal than a Tory. Team Truss, for their part, argue that the Prime Minister’s problem is that her party is packed full of ‘social democrat’ fainthearts who are running frightened from real conservatism.

It is hard to avoid the conclusion that the Tories are deep into the kind of debate that parties don’t normally indulge in until after a general election defeat: about what they stand for, and what went wrong. In Birmingham this week, it has been striking to see the vitriol with which the various factions speak about each other’s policy suggestions. After 12 years in government, the Tory internal coalition is fraying badly, with everyone blaming everybody else for what has gone wrong. Labour’s conference was by comparison a model of discipline and unity.

Truss has only been in power for a month. Leaders can live to fight another day after a bad start. Gordon Brown was hit hard by the election that never was in 2007, yet he still managed to deny David Cameron a majority in 2010. In a political era where the unlikely happens all the time, it’s impossible to rule out a Truss revival. But it’s also impossible to rule out an implosion from which the party might never fully recover.

Already, Nadine Dorries, a Johnson loyalist who supported Truss with enthusiasm in the leadership contest, has been firing warning shots, saying Truss will have to have a general election if she veers away from her predecessor’s policies. Johnson’s friends have coined a phrase for those who regret his departure – ‘Bgret’ – and are messaging each other with details of who is suffering from it.

So the Tory tribes are not uniting under a new leader: the Birmingham conference made that clear. They’re staying in formation and preparing for a tussle over the soul of the party.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in