William Kentridge’s work has a way of sticking in the mind. I can remember all my brief encounters with it, from my first delighted sight of one of his charcoal-drawn animations, ‘Monument’ (1990), in the Whitechapel’s 2004 exhibition Faces in the Crowd to my awestruck confrontation with his eight-channel video installation I am not me, the horse is not mine(2008) in Tate Modern’s Tanks in 2012. That marked a high point for the Tanks, since when they’ve tanked.

Kentridge’s is a face you don’t forget, partly because it often appears in his own animations in the guise of his beaky alter ego Soho Eckstein, partly because of the trademark vintage props – megaphones, projectors, Moka coffee makers – and oompah-band soundtracks that accompany his films. But in the 1990s, when his work first reached these shores, it stood out from the crowd for another reason: it was out of key with contemporary British conceptualism. It was ironic, yes, but the irony had a different timbre; echoing Beckmann, Grosz and Dix and Bertolt Brecht, it seemed to belong to an earlier era of northern European cultural history.

Where had Kentridge sprung from? South Africa. The son of two anti-apartheid lawyers – his father Sydney Kentridge represented the family of Steve Biko – he grew up under apartheid in a country forcibly stuck in the past, a world away from the peace, prosperity and blurred moral lines of post-war Europe. It was a place of constant state surveillance and brutal oppression, but also of clear-cut contrasts between truth and falsehood, poverty and plenty, black and white. Like the Weimar Republic, it proved a stimulating climate for radical art.

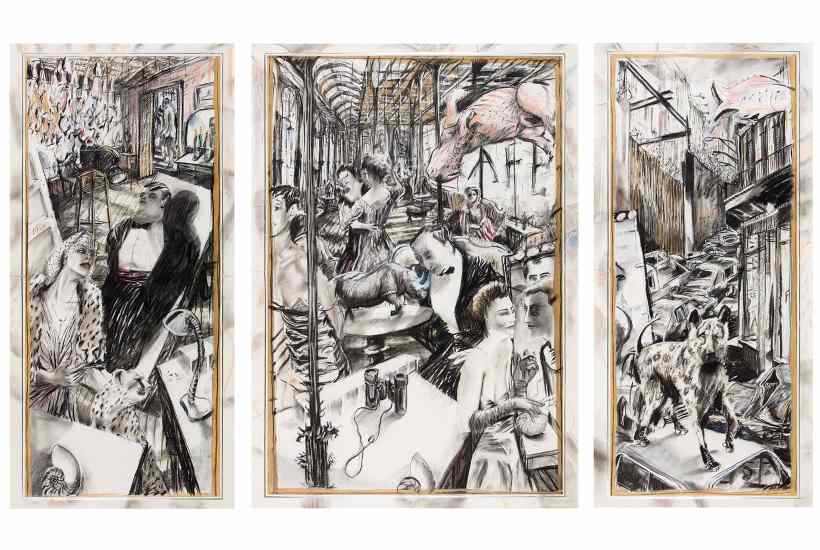

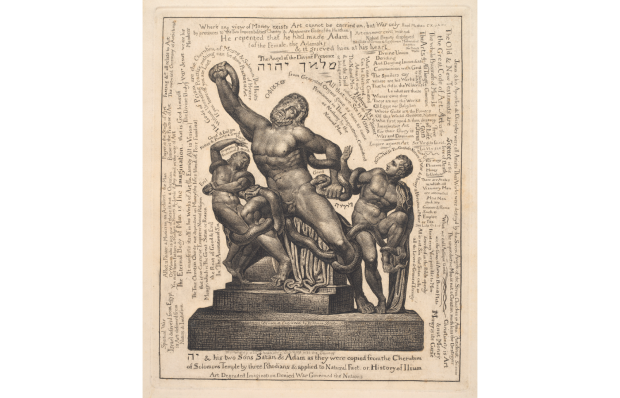

There’s almost no colour in the Royal Academy’s 40-year retrospective of Kentridge’s work; it’s all black and white or smudgy shades of charcoal in between. Nor is there a lot of what purists would term ‘fine art’. Although a brilliant draughtsman, Kentridge came to a career in art out of Johannesburg’s workshop theatre scene and he has never cut his ties with the stage. Along with props and costumes for his chamber opera Waiting for the Sybil (2019), and film footage from his Notes for a Model Opera (2015), the show includes a projection in a mechanised puppet theatre, ‘Black Box/Chambre Noire’ (2005).

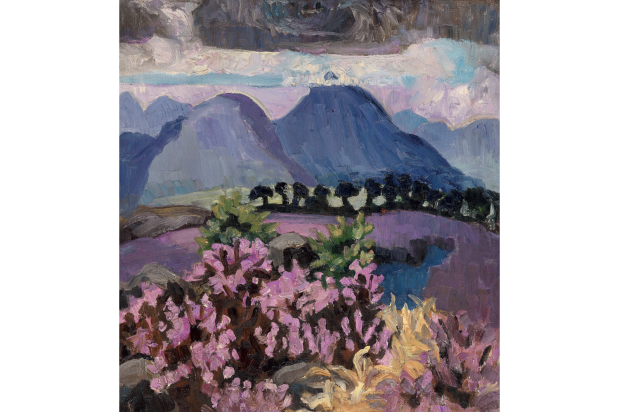

His graphic art is essentially theatrical. The 25 large charcoal ‘Drawings for Projection’ in this show were not designed to stand alone, or to stand still; they mark stages in the short animated films he has been making since 1989. Kentridge creates moving pictures by working and reworking the same charcoal drawing, erasing elements and adding others. It’s a subtle method that tracks delicate movements – the flight of a bird across a landscape or the wave of a hand – unlike the more brutal cartoon treatment of ‘Ubu Tells the Truth’ (1997), which presents racial injustice as knockabout tragedy. Aware of his privileged position as a white South African, in his Soho films Kentridge adopts the alter ego of an odious property speculator in a pinstripe suit who juggles phones and stuffs his face with food while an armoured troop carrier collects the heads of murdered Africans. But Eckstein also has a cultured side, poring over museum cases in Johannesburg Art Gallery as the institution crumbles to dust around him.

There’s always a noise pollution problem with films in galleries, but the main trouble with ‘time-based’ media is they take time. None of Kentridge’s short animations lasts longer than ten minutes, but with a dozen different films screened in one show it adds up. Don’t blame the artist – his films were never intended to be viewed en masse – it’s just that these days galleries feel they have to overload visitors to justify the rising price of tickets.

Major retrospectives tend to hold the attention by tracing an artist’s lifelong development, but Kentridge emerged fully formed in the 1980s and has remained remarkably consistent since. His means of expression vary – the show includes drawing, etching, sculpture, film, animation and tapestry – but his expression doesn’t. His art is monochrome and monotonal. The separate servings of it I’d sampled so far didn’t prepare me for a multi-course meal in which all the dishes seemed to have a similar flavour. It may be that I needed time to digest, but after three hours of intensive viewing, I left feeling I’d binged on a box set. The show is too big.

In an amusingly self-deprecating video, ‘A Lesson in Lethargy’ (2010), Kentridge’s critical self confronts his artist self. ‘Look at the way he’s sitting, look at the way he’s concentrating, hoping for some idea to come towards him while he’s busy writing,’ the critic sneers. ‘What is he writing?’ ‘The artist thinks slowly,’ responds the artist. ‘This is a lesson in lethargy’. On the evidence of this frenetic show, a bit more lethargy wouldn’t go amiss.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in