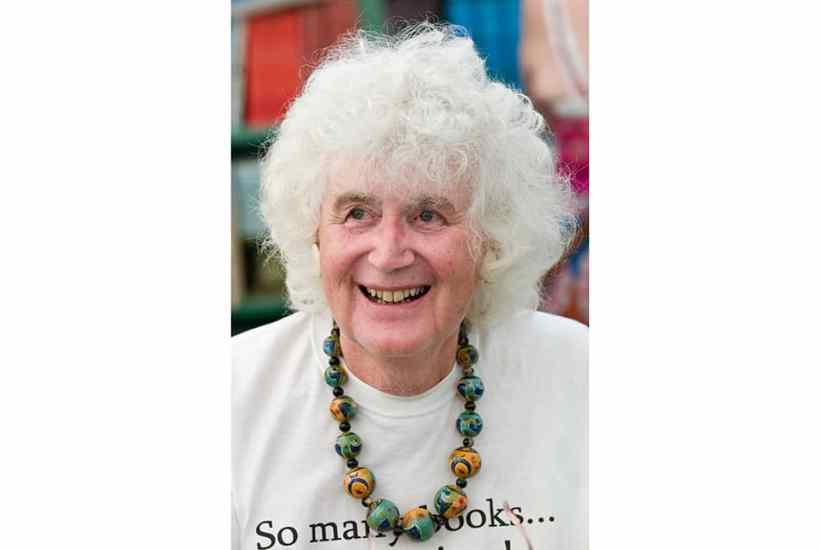

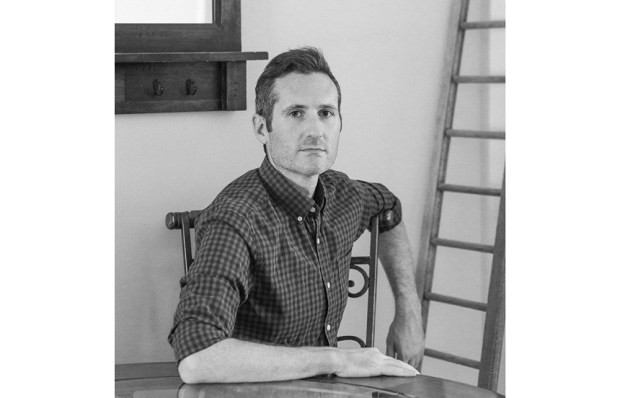

Almost two years after the death of Jan Morris, the jaunty travel writer and pioneer of modern gender transition, her first post-humous biography has arrived. (I follow Paul Clements in using the feminine pronoun throughout.) It is lively and well written, but it’s not the finished product. It lacks access to the private papers of its subject and her wife Elizabeth.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in