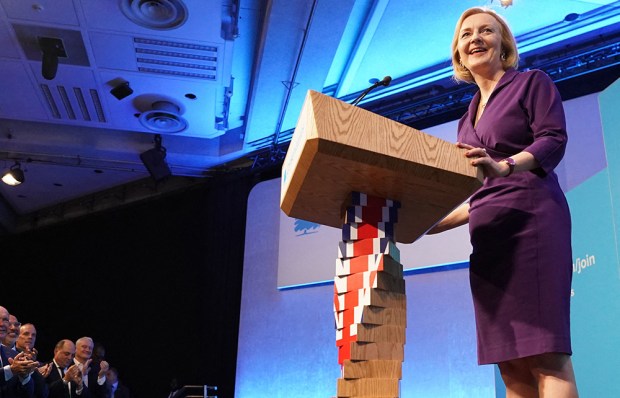

Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng are determined to show that Britain’s economy is under new management. They want to indicate through their decisions – such as cancelling the corporation tax rise and reversing the National Insurance rise –that they are breaking away from the fiscal approach of recent years.

More broadly, they want to emphasise that growth is their priority. In contrast to Boris Johnson’s attempts at people-pleasing, Truss is happy to declare she is prepared to be unpopular if that is what it takes to get the economy moving. She is dismissive of arguments about the distributional impact of tax cuts. At the same time, Kwarteng is scrapping the cap on bankers’ bonuses – a policy that is never going to go down well with voters, but does show that the government is prepared to take some criticism for measures it thinks will boost competitiveness. Kwarteng’s decision also reveals something about the government’s attitude to its new post-Brexit powers. Despite prizing sovereignty in the negotiations, the Johnson administration made relatively few changes to the rules that it inherited from EU membership – often for fear of how the public would react.

Even some ministers are nervous about how the electorate will receive this week’s package. Truss and Kwarteng’s calculation, however, is that the Tories must reassert their low-tax, pro-growth credentials.

At the same time, the energy bills packageis meant to give the government space to get on with a tax-cutting agenda. Truss’s decision to intervene to this extent, with the government directly setting the price of energy for both businesses and households, is a reminder that she knows there are some ideological fights which aren’t worth the candle. The cost of the energy package is unknowable, but there are those in Truss’s team who believe it may cost much less than feared because the wholesale gas price may well continue to fall.

It is worth remembering that one of the reasons why taxes were rising is because of the Tories’ big spending. The National Insurance rise is meant to pay for both the extra funding to deal with the NHS backlog and the cost of the government’s social care policy. Truss has indicated that she will honour those commitments while scrapping the rise.

The way Truss intends to square this circle is by boosting growth. It is certainly true that if the government can increase the UK’s growth rate then it can avoid the fiscal choices of the past few years. Truss’s argument is that ‘tax cuts and reform’ will deliver the growth that has been so elusive since 2008.

Her supporting economists are confident that the markets will give the government time and space to make this transition. But this could become complicated if the Bank of England continues with quantitative tightening. Another question is what happens to sterling, which, like many other currencies, has fallen significantly in value against the dollar recently. But if the pound continues to drop further it could entrench inflation.

Perhaps the biggest challenge for Truss and Kwarteng is time: having entered office in midterm, and after 12 years of Tory-led governments, they need to deliver quickly. This will be difficult as supply-side changes can take years to have an effect. Indeed, changes that require legislation are going to take longer just to get through parliament thanks to the packed legislative timetable and the fact that the government has no majority in the Lords. At the same time, the fact that Truss and Kwarteng have taken over with the opposition ahead in the polls and with two years to the next election could limit the impact of reforms, as businesses and investors aren’t sure that the measures will be retained after the next election.

The second question is how electorally viable Truss’s approach is. The 2019 Tory victory was based on leaning right on culture and, in Tory terms, left on economics. Truss wants a very different economic policy. Her emphasis is on competitiveness: the rumour that she will change the name of the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities to the Department for Growth is revealing.

Truss’s energy package for both households and businesses suggests that she is not afraid to spend big (the energy package is likely to cost more than furlough). But her tone is very different to Johnson’s. Truss has long been convinced that those voters who flipped to the Tories in 2019 actually want distinctively Conservative policies. Labour will attack Truss in classic left-right terms for her tax cuts for ‘big business’, her refusal to bring in a new windfall tax and her decision to remove the bankers’ bonuses cap. So the reaction to Friday’s statement in the coming days will be an early test of whether Truss’s theory about the Tories’ 2019 converts is correct.

The third question is how big is Truss prepared to go? Removing the cap on bankers’ bonuses is, ultimately, not going to affect the growth rate of the whole economy. The reform that would make the biggest impact on the economy would be in planning. Johnson abandoned meaningful planning changes amid a backbench backlash following the by-election defeat in Chesham and Amershamin June last year. The investment zones that the government is proposing appear to be an attempt to do planning reform on a local level. This is better than nothing and – given the difficulties of doing anything in this area – commendable. But a piecemeal approach won’t have the same effect as a liberalisation across England. Indeed, there is a sense that planning is becoming the early 21st-century equivalent of industrial relations in the 1960s and 1970s: it is holding the economy back, but no one has enough political capital to see through the necessary changes.

There will be another so-called ‘fiscal event’ in the coming months, so this week may not mark the end of the government’s radicalism. But it does show that Truss and Kwarteng want their economic dividing line with Labour to be tax cuts – rather than the deficit, as it was for Cameron and Osborne. Labour will counter with the question: tax cuts for whom? This week has started the debate on which the next election may turn.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in