Are Britain and France at the dawn of a new Entente Cordiale? It’s reported that France will be the destination for the first state visit of King Charles, and in New York this week Liz Truss and Emmanuel Macron took a break from the UN General Assembly for 30 minutes of ‘constructive’ talks.

There are many in France who long for a closer relationship with Britain and, at the same time, for a gradual decoupling from Germany.

I wrote in April last year of the growing French scepticism towards Germany; of how in the words of one current affairs magazine, France has for decades been ‘fleeced’ by its eastern neighbour economically.

Rare were the politicians who pointed this out. One exception, Marine Le Pen, a long-standing critic of Germany, declared in 2021 that were she ever to become president she would seek a ‘divorce’ from the Franco-Germany couple in favour of establishing a closer relationship with Britain.

Hers is no longer a lone voice because the energy crisis has taken the French scepticism mainstream.

Twelve months ago the European think tank, the Jacques Delors Institute, published a policy paper that praised Germany’s energy strategy of energiewende (energy turnaround). The paper concluded that in rejecting nuclear energy, ‘Germany is thus successfully completing the “energy turnaround” that began more than 20 years ago.’

Anyone who dared challenge this orthodoxy was mocked, as Donald Trump was at the UN General Assembly in 2018 when he warned the Germans that they were making a serious mistake in becoming ‘totally dependent on Russian energy’. As the Washington Post reported, the reaction among most delegates was one of mirth and the German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas ‘could be seen smirking alongside his colleagues’.

Last week Olivier Marleix, the leader of the centre-right Republicans in the National Assembly, wrote an op-ed in Le Figaro that savaged Germany’s energy policy and also criticised Emmanuel Macron for going along with it.

Marleix expressed his anger at EU president Ursula von der Leyden’s proposal earlier this month to introduce a price cap on countries that produce renewables, hydropower and nuclear energy, and whose production costs are lower than those of coal and gas power stations. This levy on revenues would subsidise member states who have to buy gas to produce electricity, such as Germany. ‘Taxing the good performers to give back to the bad performers is a surprising idea,’ remarked a sardonic Marleix.

Taking an opposite stance to the Jacques Delors Institute, Marleix said Germany had only themselves to blame for their plight because over many years they had made a series of ‘wrong choices’ over their energy strategy.

Marleix is a protégée of former president Nicolas Sarkozy, an advocate of nuclear energy during his time in office. In September 2007, shortly after he was elected president, Sarkozy met Angela Merkel in Berlin where he advised the Chancellor not to forsake Germany’s nuclear energy. ‘We cannot remain in a situation in Europe where, a century from now, there will be no more gas, where in 30 or 40 years, there will be no more oil,’ said Sarkozy. ‘No one can imagine that wind turbines will be used to power all of Europe.’

Sarkozy wanted France and Germany ‘to have energy ambitions in the same direction’ but his advances were spurned by Merkel. Indeed, four years later the Chancellor accelerated the phasing out of all 17 German nuclear reactors, while at the same time initiating a campaign to pressurise France to follow suit.

This strategy was laid bare in a recent book published by Bernard Accoyer, a former Republican MP who served as president of the National Assembly under Sarkozy. Subtitled ‘The attempt to scuttle the French nuclear industry’, the book describes how France’s nuclear energy programme, launched in 1974 under president Georges Pompidou, gave it not only cheap electricity for households and businesses, but a competitive advantage over Germany.

This was resented by Merkel who – with the support of Brussels and the French Greens – conspired to introduce legislation to reduce EDF’s dominance in the EU electricity market by forcing it to sell a quarter of its nuclear electricity production to its competitors at knockdown prices. ‘Everyone knows that Germany cultivates the art of using the European institutions to increase its influence and develop its efficiency,’ wrote Accoyer.

That they’ve been able to get away with it is because of the servility of Sarkozy’s successors, François Hollande and Emmanuel Macron, ‘who are trying hard to imitate a German energy strategy that serves Berlin’s interests but harms our own’.

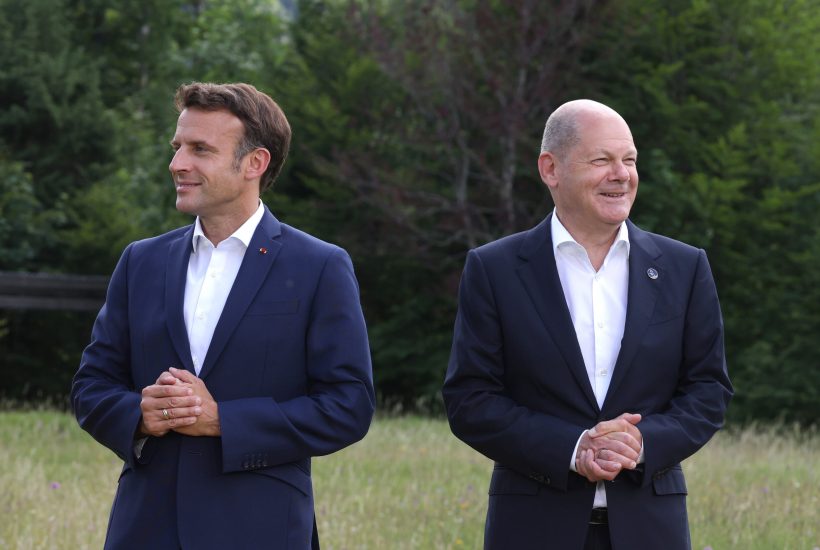

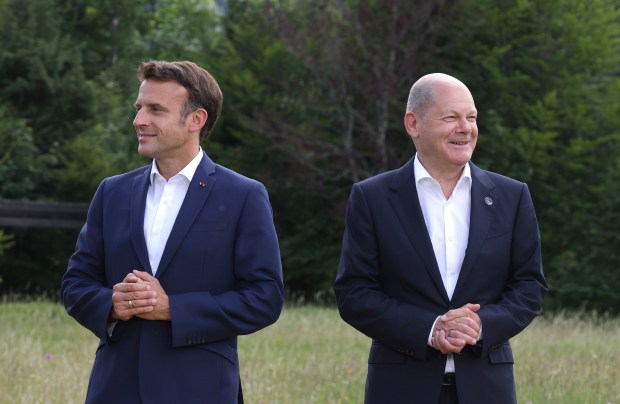

Macron believe the price cap proposal is a good idea. ‘We will show solidarity [with Germany] by strengthening our exchanges of gas and electricity,’ he tweeted on September 5. ‘We will defend the implementation of a European mechanism which will involve energy producers whose production costs are well below the market price.’

Macron and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz have agreed a deal whereby from next month France will send 5 per cent of its gas reserves to Germany through the winter and in return they will receive electricity from their neighbour. France should have no need of electricity from Germany but 32 of its 56 nuclear reactors are not functioning, and one of its principal plants, Fessenheim, was closed by Macron in 2020 with the encouragement of Germany. The German Environment Minister at the time, Svenja Schulze, declared that the closure would make Germany ‘safer’, and she promised to keep lobbying France to phase out all its reactors, saying ‘Nuclear power is not a climate saviour’.

The war in Ukraine has exposed other cracks in the Franco-German relationship. In June the economist Bruno Alomar and the Republican senator Cédric Perrin wrote an op-ed in Le Monde in which they accused Germany of acting unilaterally in announcing its commitment to increase defence spending by €100 billion.

Not that this was the first time Germany had made a decision without consulting its EU partners, noted the authors, citing as other recent examples the decision to phase out nuclear energy and its migration policy in 2015 that ‘pushed a decisive fringe of the British population towards Brexit.’

Like Marine Le Pen, Alomar and Perrin concluded that the Franco-German couple has run its course and it is time France looked for other European partners. By which they mean Britain.

It is no longer Perfidious Albion that the French distrust, but perfidious Allemagne.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in