‘Better use your sense,’ advised Bob Dylan: ‘take what you have gathered from coincidence.’ John Higgs is a master of taking what he can gather from coincidence – or, as he would insist, synchronicity. From the filigree of connections and echoes in the KLF (Discordianism through the lens of 1990s pop provocateurs) to the psychogeography of Watling Street to more recent deep dives into William Blake, he confronts the modern Matter of Britain: who wields power, and who resists it?

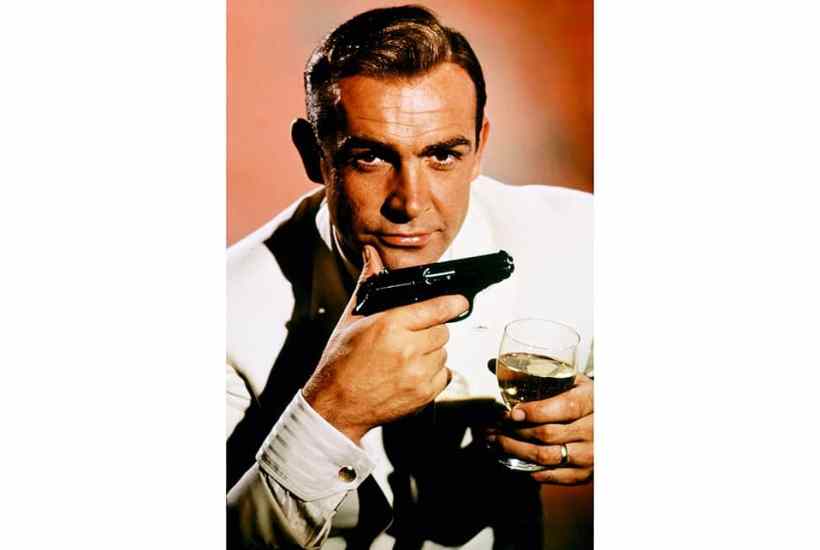

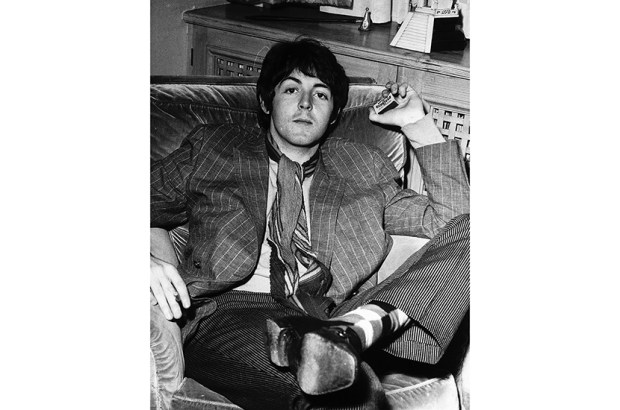

Love and Let Die starts with another perfect coincidence, namely that it was 60 years ago – to be precise, 5...

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in