In her memoirs, Raisa Gorbacheva recalls the moment when her husband turned from bureaucrat into reformer. ‘I’m in my seventh year of working in Moscow,’ he told her as they were walking together one evening. ‘Yet it’s been impossible to do anything important, large-scale, properly prepared. It’s like a brick wall – but life demands action. No, we can’t go on living like this any more.’ It was the first time, she wrote, she heard him say such words. ‘That night, a new stage began that brought big changes.’

Mikhail Gorbachev’s death this week has led to much analysis of his legacy. He is admired more in the West than in Russia. When he won the Nobel Peace Prize, his critics drily noted that it was not the prize for economics. While countries in eastern Europe reclaimed statehood and obtained democracy and prosperity, Russia slid into anarchy and gangsterism. The results of this failure lie before us now: there is war in Europe once again, energy prices are surging, and millions fear a winter of misery and penury.

The current crisis also has its roots in the western hubris that followed the end of the Cold War. There is still a widespread myth that the West ‘won’ and that Gorbachev effectively admitted that the communist game was up. In reality, although Gorbachev may have buried the USSR, he was a committed Marxist–Leninist whose aim – which he stated in private and public – was the ‘perfection, improvement, acceleration and finally the restructuring’ (or perestroika) of the communist system.

There was no great global battle of ideas that ended with democracy and free enterprise emerging victorious – much though it suited the democratic world to pretend other-wise. It was naive to assume that Russia would naturally imitate the West. Germany thought: why not accept cheap gas from Putin? It seemed inconceivable that Russia, whose economy was smaller than Italy’s, could prove a threat. Surely the collapse of the USSR had taught Russians a hard lesson about what system managed things best.

No such lesson was ever accepted in Moscow. Gorbachev was seen as a sellout. Vladimir Putin has called the demise of the Soviet Union ‘the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century’. When Putin spoke about recreating an empire of Russian people – his Russkiy Mir – his comments were ignored or laughed off by many in the West. Didn’t such ambitions die off with Gorbachev and the Afghanistan debacle? Surely there would be no popular support for such clearly deranged adventurism?

The USSR collapsed under its own contradictions. It was bankrupted by the nuclear arms race and its one-party state failing in a post-industrial age. But there was never any real Russian equivalent of the popular revolutions which ended communism in eastern Europe. This matters, because there is little reason to think that a popular revolution will depose Vladimir Putin. Those who wish to fight for change are hobbled. Alexei Navalny, Putin’s main opponent, flew back from exile to be incarcerated. Putin, wishing to demonstrate to Russians and the world what fate befalls his critics, was happy to let him make that point.

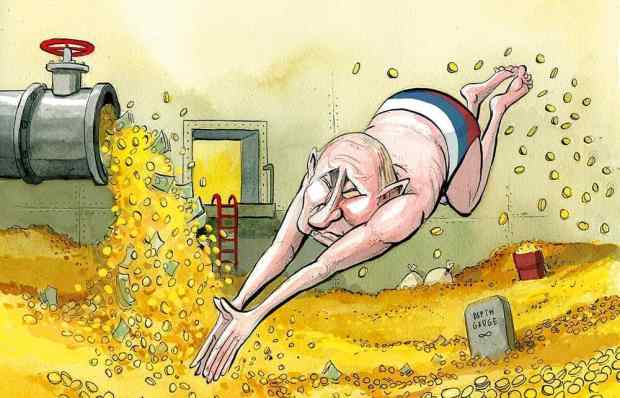

It’s possible to draw parallels with the final days of the Soviet Union. Putin’s gangster economy is leading to the same economic stagnation that beset the USSR then. One of the nails in the coffin of the Soviet regime was the ten-year war in Afghanistan, in which 13,000 soldiers perished and the authorities were unable to justify the losses to a sceptical public. In just six months, even more Russian lives have been lost in Ukraine, and Putin’s reluctance to institute conscription suggests that he does not want to push public opinion too far. But there is no sign of effective opposition to Putin, or any reason to believe that he would not be replaced by someone worse if he were to go.

The country whose example offers most cheer to Russians who want reform is Ukraine. After its independence in 1991, the country followed Russia’s post-Soviet descent into chaos. Power was picked up by oligarchs and organised criminals. But over the years, popular rebellion – the 2004 Orange Revolution and the 2014 Maidan Revolution – showed that the public would revolt against corruption and overthrow presidents if need be. There was a demand for something better. Slowly but undeniably, that’s where Ukraine was heading.

The real threat Volodymyr Zelensky presented to the Kremlin was that he showed reform was possible. Before the invasion, Ukraine was attracting investment and creating prosperity. Its oligarchs were becoming steadily less powerful and sometimes being sent on the run. The whole point of electing a television actor as president was that, as a political novice, he would not be compromised as previous leaders had been. Ukraine had deep problems with corruption – it still does now. But the country was cleaning up, liberalising, and showing its neighbours what was possible. This is the experiment that the Kremlin sought to end.

The Russian people today are also victims of Putin. Millions of them will think, as Gorbachev did, that ‘we can’t go on living like this any more’. But they need to see that there is a viable alternative. Gorbachev used to quote the Russian poet Apollon Maykov: ‘The darker the night, the brighter the stars.’ Those who want a better Russia are in dire need of reasons to be hopeful.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in