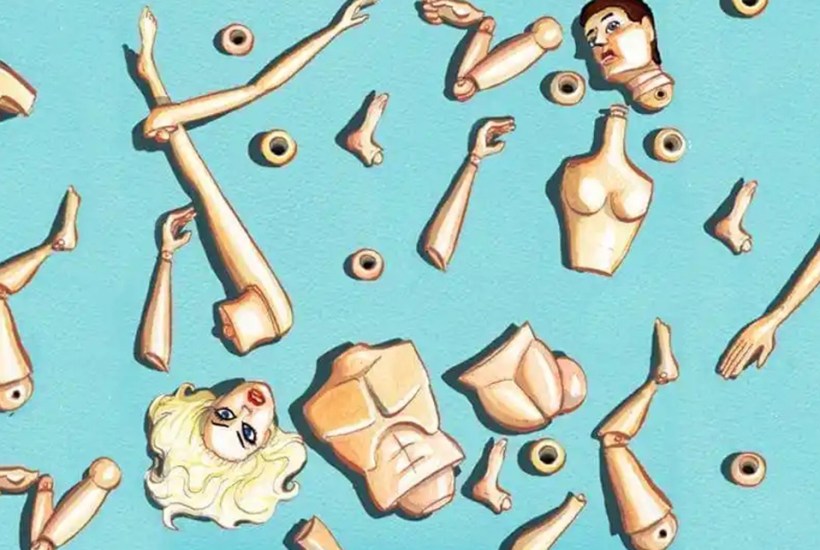

The publication this week of the Cass Review into gender-identity services for young people marks a welcome return to reason in an area of medicine which for the past few years has been driven by identity politics. No one is denying that there are those who deserve psychological – and in some cases physical – help to cope with their condition. But the explosion in the number of children treated on the NHS for gender-identity issues (and in many cases being given powerful drugs with severe side effects) should have set alarm bells ringing long before it did.

The NHS first set up its Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) at the Tavistock Clinic in 1989, and for the first two decades of its existence it was a small outfit with a low profile. At first, it treated fewer than ten children a year, most of whom had by adulthood overcome their feelings of gender incongruence. A very small number went on to be prescribed hormone treatment from the age of 16. That all began to change after 2009, when the clinic treated 51 children and adolescents and thereafter numbers rose steadily until in 2014 there was a further massive jump. By 2016, the Tavistock was treating 1,700 children and not only had the numbers greatly increased but the clinic’s patients were ever younger. Initially, most cases had been boys who felt they ought to be girls, but by 2016 two-thirds of cases were female.

From 2014, puberty blockers became routinely prescribed by GIDS in spite of a lack of research data

Medical professionals should have been alerted to what looked increasingly like a classic case of mass mania. But far from questioning the dramatic changes, GIDS ploughed on, offering powerful, often dangerous, drugs to vulnerable children.

The clinic adopted what became known as the ‘Dutch protocol’, derived from a single case of a child in the Netherlands administered puberty blockers in the late 1990s. From 2014, puberty blockers became routinely prescribed by GIDS in spite of a lack of research data on the benefits to the children themselves. When the data did begin to dribble through, it was not favourable. Preliminary results from a study which became available in 2015 but was not formally published until 2020, failed to identify quantifiable benefits from the treatment. As Dr Hilary Cass notes, the routine administration of a treatment whose efficacy has not been proven in controlled trials is a serious departure from normal medical practice, yet for some reason it went unchallenged in this one corner of the NHS.

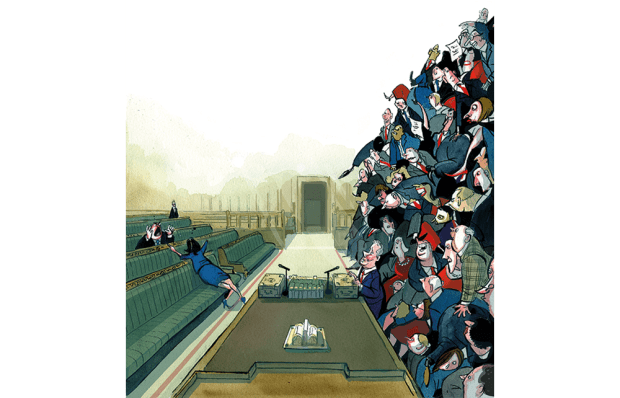

In the end it was an aggrieved former patient, Keira Bell, who took out a case in the High Court against her prescription for puberty blockers at the age of 16. Her lawyers argued that she had not been sufficiently mature at that age to give consent to a treatment which she has since come to regret. She won her case, although it was later overturned by the Court of Appeal on the grounds that the appeal judges believed it was the role of doctors, not judges, to decide what was in the best interests of a patient. Worse, the court ruled that children should be allowed to take puberty blockers without parental consent. The Court of Appeal judgment overlooked the fact that a growing number of doctors and other medical staff – including whistleblowers within GIDS – thought puberty blockers dangerous and were increasingly alarmed at what was going on at the Tavistock.

An investigation into GIDS by the Care Quality Commission followed in 2020, in which the clinic was judged to be ‘inadequate’. One particular area of concern was its failure properly to record patients’ capacity for consent for the treatment they were given, especially with regard to autistic children. In 2022 the NHS closed down GIDS, transferring treatment to regional centres.

What can be learned from this disaster? As Dr Cass argues, puberty blockers should never have been prescribed ahead of formal medical trials. The evidence for their effectiveness, and their long-term safety, simply does not yet exist. Moreover, she recommends that no child should ever be subjected to such treatment without first being screened for neurological conditions, autism and mental illness, all of which might benefit from less damaging interventions.

There is a wider issue here, which is the influence of political activism on the medical profession. Dr David Bell, a former psychiatrist at the Tavistock, who published a report on its activities in 2018 and was threatened with investigation for his trouble, has spoken of how children treated there would often give ‘rehearsed’ answers, as if they had been instructed by outsiders. Aggressive lobbying by trans-rights groups, which has included throwing the hyperbolic charge of ‘genocide’ at those who oppose its views, has made people fearful of opposing the idea that children have the capacity to consent to treatment which will have a serious effect on their future lives.

As it happens, the NHS has pre-empted Cass’s final report by last month banning the prescription of puberty blockers to children – although it seems there are still exemptions. Common sense has, eventually, prevailed. But it is deeply worrying that for several years an NHS-run clinic was allowed to pursue what looks like an ideologically driven treatment programme for vulnerable children, and acted to silence its internal critics. Never again should any area of medicine be allowed to vanish into such a black hole.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in