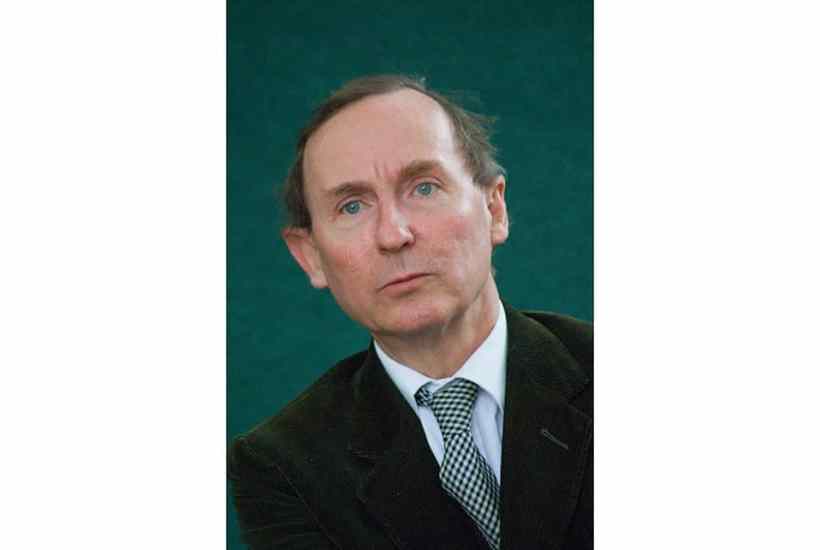

‘Spare thou them, O God, which confess their faults.’ A.N. Wilson seems, on the surface, to have taken to heart the wise words of the Anglican general confession.

Aged 71, he looks back on his life and career and records his regrets and failures both private and professional. His major concern is the failure of his marriage, at the age of 20, to Katherine Duncan-Jones, the Renaissance scholar.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in