Well, thank goodness for that. Just as it seemed the England’s women’s football team might be about to extend the nation’s 56 years in search of a continental football title, a glorious release courtesy of an injury time winner from Chloe Kelly broke the spell. Saving us all from yet more psychological trauma like that inflicted by Gareth Southgate’s men’s team’s recent near misses, the Lionesses’ victory sent the stadium and the country ‘into raptures’.

It was a terrific game and crowned what has been a fine tournament. To paraphrase a great war-time patriot, no one would quibble with ‘allowing ourselves a brief moment of rejoicing’. But then, for the good of the game, and our collective sanity, some sober reflection on two key questions would be useful: what does the victory really mean and will it really lead to an explosion of interest in women’s football?

For the first it appears necessary to stress that this was fundamentally a sporting triumph, not a political one as many seem keen for us to believe. The BBC, naturally, led the way and their politicising of everything connected to the tournament was relentless. ‘A watershed moment for gender equality’ declared BBC news last night, summing up the tenor of their coverage throughout. At time it got silly, as when Women’s Hour devoted a segment to discussing whether the nickname ‘Lionesses’ was sexist.

The nadir was the comment by presenter Eilidh Barbour suggesting the England team were deficient in the diversity department as all 11 players and five substitutes were ‘white’. This implication that the hard-working men and women who devote their time, often for no reward, to organise and promote women’s football across the UK, were at fault for this monochromatic calamity, earned the corporation hundreds of complaints. But this only seemed to please Ms. Barbour who, spectacularly misreading the mood, tweeted she was ‘glad we are having this conversation’.

I’m glad this conversation is happening. Football is a game for all. It has never been about criticising this #ENG team, it’s about looking to the future and the pathways so girls can all have the same opportunities to be a Lioness 🦁 https://t.co/gs506fiz10

— Eilidh Barbour 💙🤍 (@EilidhBarbour) July 19, 2022

In the end, all that seemed a bit ridiculous, and superfluous, and boring, as did the knee taking (all played out), the pride armbands. The tiresome finger-wagging ad campaign of sponsors EE (part of the BT group) trying to convince us that the players were akin to modern day suffragettes competing as much to fight sexism and online hate as trying to win a football tournament was up there too. Most people, I suspect, ignored all this and record numbers watched the tournament for its sporting qualities and entertainment value, not in solidarity with supposedly oppressed minorities.

And therein lies the key to answering the second question. Whether England’s victory leads to the advance of women’s football to a position that challenges the global reach and commercial power of the men’s game depends not on the media’s hysterical boosterism or the portrayal of women’s football as a theatre of the culture wars but on the paying public. And on this score, the gushing optimism of last night may be misplaced.

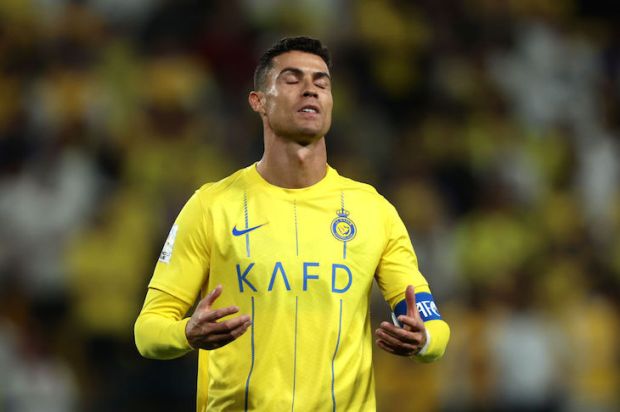

(Getty Images)

(Getty Images)

I cite as evidence here Japan’s victory in the 2011 World Cup, with respect to the Lionesses’, a greater triumph than England’s. Japan were not the tournament favourite and was not playing at home. In the final, they faced the seemingly unbeatable USA, who had won the previous 25 meetings between the two nations. The Japanese players, many of whom had part-time jobs, were about half the size of their Amazonian opponents. They were huge underdogs yet pulled off a thrilling victory (perhaps the best World Cup final ever – men or women) made all the more meaningful in Japan as it came just months after the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami which had claimed the lives of 18,000 people.

It seemed the perfect springboard to launch Japanese women’s football towards parity with the men. Japan wasn’t even handicapped, as most of the rest of the football playing world is, with a century-old men’s game with multi-generational ties of loyalty (the J-League is just 30 years old). Other sports, such as volleyball and ice-skating had female stars more popular than their male counterparts. If women’s football were to challenge the men anywhere, Japan might be the place.

It didn’t happen. After a brief mini-boom, the women’s game returned to pretty much the level it was at before. Attendances remain low and even the top players relatively anonymous. And it wasn’t because of ingrained sexism or lack of investment. The fans, of both sexes (Japanese women follow men’s football in huge numbers – there is even one team, Jubilo Iwata, with a predominantly female fan base), just carried on preferring the men’s game. It turns out there was a world of difference between getting behind the national team in a quadrennial showpiece and regular attendance for run-of-the-mill domestic club fixtures.

Will things be different in the UK? Perhaps. No doubt the BBC will still push women’s football zealously, and England’s Euro 2022 ‘heroines’ will prove powerful advocates.

But whether their achievement really leads to tens of thousands trudging along each week, year after year, to support their local club teams in less glamourous surroundings and for far lower stakes, remains a purely commercial question. If the paying public want it, it will happen. If they don’t, it won’t.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in