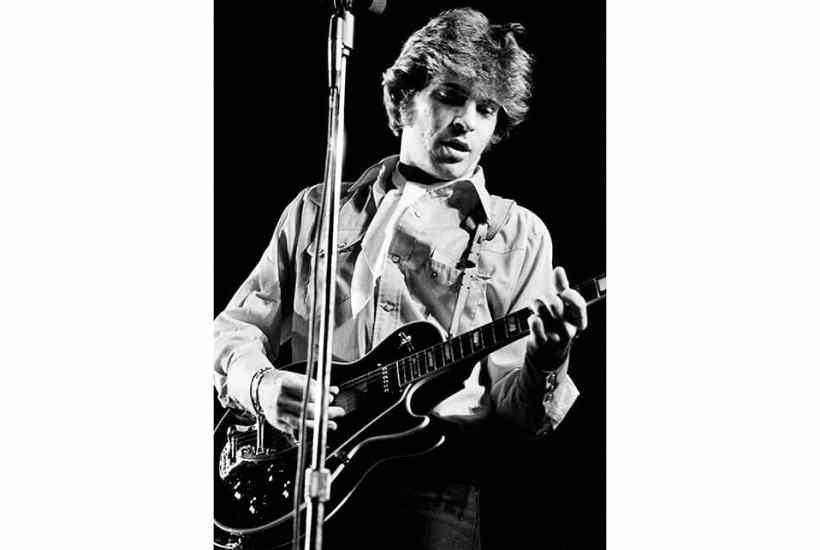

Million-selling rock bands are rarely happy families. They are an uneasy combination of a creative alliance and a business partnership, which is frequently thrown together on an ad hoc basis by people barely out of their teens. They are tested to destruction by long hours, minimal sleep, deafening noise, international travel, a bedroom schedule that would have made Caligula blush and a seemingly unending cocktail of legal and illegal stimulants.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in