‘These artists are offering other ways of seeing,’ says Ekow Eshun, curator of In the Black Fantastic, and from the moment you push open the Hayward’s heavy swing doors you see what he means. Outside, a world of grey utilitarian concrete; inside, a vibrant crew of invaders from planet Zog glittering like Technicolor Pearly Kings in bright carapaces of beads, sequins and buttons.

The kind of thing a nimble-fingered alien might come up with if his spaceship crash-landed in a haberdashery department, Nick Cave’s ‘Soundsuits’ make Ziggy Stardust look Earthbound (see below). Brought up with seven brothers by a single mother in Missouri, Cave learned early how to pimp hand-me-downs and his suits are exquisitely tailored. Slightly larger than life to accommodate performers – he’s a former member of Alvin Ailey’s American Dance Theater – when standing vacant they have the benign presence of tutelary spirits. Cave made his first after seeing footage of the LAPD’s beating of Rodney King that sparked the 1992 Los Angeles riots. Feeling vulnerable as a black American male, instead of rioting he constructed a protective shell. The handful of examples gathered here is a tiny sample of the more than 500 he has made since. They’re called ‘Soundsuits’ because of the noises they make when worn; when silent, they make a visual splash.

‘Soundsuit’, 2014, by Nick Cave. Credit: © Nick Cave. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. Mandrake Hotel Collection

‘Soundsuit’, 2014, by Nick Cave. Credit: © Nick Cave. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. Mandrake Hotel Collection

Cave is one of 11 artists from the African diaspora who have each been given a room to themselves in which to reimagine our imperfect world in pictures. There are mercifully few words. Tabita Rezaire’s film installation ‘Ultra Wet – Recapitulation’ (2017) suggesting that ‘sexuality is a construct’ is as preachy as this exhibition gets, and Sedrick Chisom’s titles – ‘The Wholly Avoidable Death of Mighty Whitey, The Last Drunk Dionysian Hero, AKA The Wholly Tragic Birth of Fragile Narcissus’ (2020) being one example – as prolix.

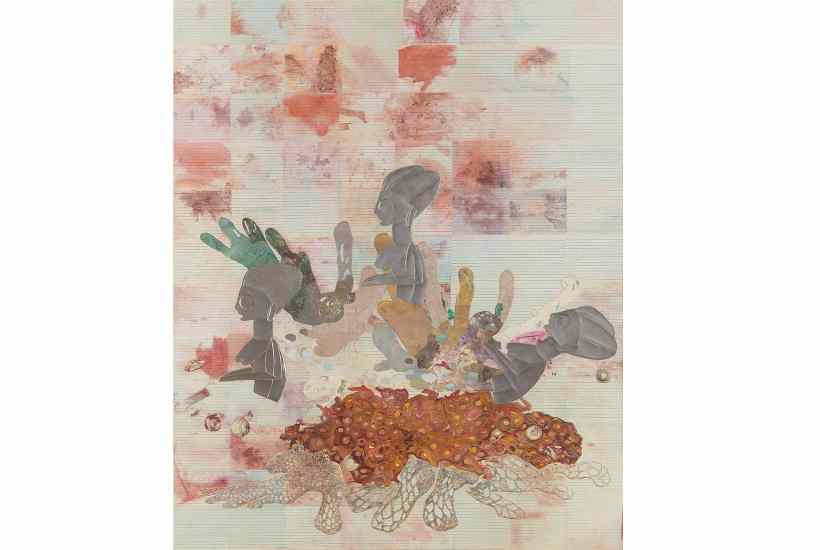

Chisom lets his titles talk over his images; Wangechi Mutu believes in the power of art alone ‘to imbue the truth with a sort of magic… so it can infiltrate the psyches of more people, including those who don’t believe the same things as you’. Her visual language is surrealism, the favoured lingo of psychic infiltration: she sticks it to the man with collage. Snipping pages out of porno mags and engineering manuals, she cooks up a bitches’ brew of monstrous cyborgs, attacking the objectification of black women by vandalising western myths of female beauty. The results are terrifying from a distance, worse from close up when you see eyes and lips implanted with breasts and buttocks and gaping mouths crammed with machine parts. Francis Bacon would have approved; she too has taken inspiration from illustrations of diseases in medical textbooks.

In Mutu’s ‘The Screamer island dreamer’ (2014), the mythical Nguva who haunts the East African coast in human guise luring unsuspecting victims to their deaths is shown in her true colours as a spiny sea monster with prehensile teeth champing to drag her prey to a watery grave. Sirens are a theme; it must be something in the water. Chris Ofili relocates the myth of Odysseus and Calypso to Trinidad – where he now lives – island home of the music that shares a name with the nymph of Ogygia. Reimagining Homer’s enchantress as the fishtailed African water spirit Mami Wata, he depicts her in a series of recent paintings in sinuous clinches with a black Odysseus. In a life-sized bronze he gives the Annunciation similar treatment, envisaging the Angel Gabriel’s visit to the Virgin Mary as an erotic coupling of horny supernatural beings. If it’s meant to shock, it doesn’t; it just looks kitsch. Take away Ofili’s elephant dung and there’s not a lot left.

Ellen Gallagher’s room feels like an aquarium with windows on to magical underwater worlds. Her monumental watercolour series ‘Watery Ecstatic’ conjures a coral-coloured aquatic ecosphere aglow with mysterious marine life forms, the watercolour saved from wishy-washiness by the addition of crisp detail in precision-cut paper. Her 2019 series of large oils, ‘Ecstatic Draught of Fishes’, has a paler palette of greyed pinks and greens dispersed in clouds of scintillating bubbles. Taking Turner’s ‘Slave Ship’ as a starting point, it envisages the unborn babies of drowned pregnant slaves learning to breathe underwater and wandering the ocean floor as silvery wraiths evoking African Fang figures.

In a quieter register than the rest of the show, Gallagher’s imagery reverberates for longer. Like Cave’s ‘Soundsuits’, her paintings combine exquisite facture with oblique meaning, representing a victory of the imaginatively crafted over the conceptual. It’s the general absence of post-modern irony from this exhibition that makes it such a tonic; for an enervated western audience, that’s fantastic in itself.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in