Facing up to the prospect of one’s own mortality is always jarring; but when you’ve spent your life trying, and sometimes failing, to save others from a terrible death, it carries the knowledge that the journey may be more traumatic than the fear or grief of the end.

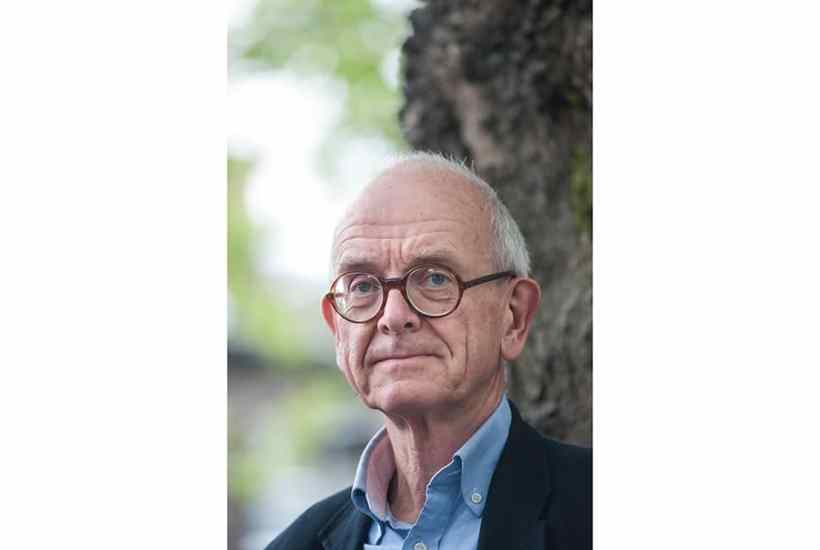

These are the concerns with which Henry Marsh, the eminent neurosurgeon and author, grapples after his own diagnosis of advanced prostate cancer more than a year ago. He believes this book will be his last and, unsurprisingly, he seems to be cramming everything into it. It makes for a discursive read and jumps about chronologically and topically, as if he wants to include all his important final thoughts. But since he’s deeply reflective, the result is a bit like sitting in the pub with the smartest person you know.

There are three sections: ‘Denial’, ‘Therapeutic Catastrophising’ and ‘Happily Ever After’, which reflect the various stages of grief (denial, pain/guilt, anger, depression, reconstruction and acceptance). But the categories merge, and Marsh combines the description of his cancer treatment with themes, general and personal, that have long preoccupied him: ethics, philosophy, teaching and training doctors, creativity, physical and cerebral fitness and his family. It’s evident that he is more concerned with high standards for himself and others than with hubris. But inevitably there’s a difficulty, after a life of high achievement, in adapting to being a patient, the passive object of other people’s decisions.

Marsh is a fair man, both in his appraisal of his treatment and his private life, critical of his faults and equally ready to give positive and negative feedback. He is justifiably concerned with the importance of good doctors and nurses, and the need for medics to show they genuinely care about their patients – to listen and have time for questions. Much of what he says reflects elementary doctor-patient communication taught in medical school; yet it’s easy for doctors with vast workloads to rush, seem uninterested or detached, or fail to discuss their decisions. Marsh rightly warns of the danger of power and corruption in medicine – cockiness is the downfall of many. He gives examples of his own mistakes; and he also shows how honesty, apology, empathy and a determination to rectify errors can go a long way to console many wronged patients.

A brain scan before his prostate diagnosis showed cerebral atrophy and ischaemia, characteristic of ageing. Marsh is more frightened of dementia than of death, and the idea of being severely incapacitated – paralysis, incontinence – from the spinal spread of his cancer horrifies him. He makes a convincing case for assisted dying.

The most touching parts of the book concern his family. He creates elaborate fairy stories every night for his granddaughters on video calls during the pandemic. And his love and concern for his wife Kate is equally moving, especially when they are forced to be apart. But his cancer diagnosis does not dent his dry sense of humour. The radiotherapy machine makes a noise like ‘a distant chorus of mocking frogs, beside themselves with hysterical laughter’; and hormone therapy gives him ‘the plump and hairless body of a eunuch… an outsize, geriatric baby’. Self-deprecation has always been his forte.

Along with basic neurophysiology there is much discussion about the sheer capacity of the human brain. Marsh marvels at the speed with which an impulse is transmitted from sensory receptors to the brain and back again. The third-of-a-second time lapse between stimulus and our conscious perception of it is, of course, fascinating. But personally what I find even more astonishing is how a cat or dog will respond to a noise several milliseconds before we do.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in