Could Russia triumph? There’s a growing sense that, as the months wear on, Ukraine’s resistance is faltering. The West is losing interest in the conflict and the unthinkable is being said: Putin is winning the war on and off the battlefield.

The image of countless hordes of Russian troops grinding down the Ukrainian defences with a 3-to-1 advantage in artillery is at first glance quite convincing. Meanwhile, off the battlefield, the ruble rate is sky high, and sanctions seem to have no discernible effect on the war. Putin’s fiercest opponent Boris Johnson is leaving office, and the energy-dependency of Europe seems to play right into Russia’s hands.

Putin now occupies nearly 25 per cent of Ukraine and is attempting, with limited success, to Russify these areas. Territorial gains in Donbas are important, if mostly symbolically – particularly as the invasion took place under the pretext of rescuing the region from the Ukrainian ‘Nazis’. Yet these gains have come at a high price: Putin recently declared an ‘operational pause’ in the fighting, claiming the soldiers should ‘have some rest’. But it’s a lot more likely this is a sign of depletion, and that no major new offensive is possible until more reserves arrive from Russia to make up the losses.

This, at least, is the assessment of the head of MI6, Richard Moore, who said this week Russia was about to ‘run out of steam’. ‘Our assessment is that the Russians will increasingly find it difficult to find manpower and materiel over the next few weeks,’ he told Aspen’s security forum, in a rare public appearance.

This tallies with indications of the growing Russian death toll on the battlefields of Ukraine. Although Putin is clearly prepared to tolerate a huge number of Russian fatalities (the UK government conservatively estimates them at 15,000: the figure of Russian dead in nine years of the Afghanistan war), the current attritional nature of the war has made the availability of operational reserves a crucial factor, and the barrel is now not so much being scraped as scoured. In late June and early July, the HeadHunter website revealed job vacancies under the heading ‘Military Serviceman Under Contract’, uploaded by the Federal Service of the National Guard (after the RBC news agency applied for the job with a request for clarification, the advert was taken down). More recently, manpower shortages have forced the Russian army to hunt for personnel among the country’s prison population, to replenish the Wagner mercenaries group.

There have been other signs that Russia’s military is struggling. At the end of June, a new law was proposed allowing secondary school graduates in Russia to sign army contracts without previous training or without having served in the army draft (at present, contracts can only be signed after three months of draft service). It was subsequently put aside and may well have been a litmus-test of the public’s mood.

Revealing, too, was a recent closed poll of the Russian public conducted on the orders of the Kremlin, its results subsequently obtained by the Meduza news outlet. A third of Russians, they reported, are convinced the war must be stopped immediately. Taking into account the repressive laws in Russia that bar open scepticism about Putin’s invasion, this figure is likely to be an underestimate. Russian society may very well be split down the middle on this issue, with any future mass mobilisation thus bringing unimaginable consequences.

The only answer, it seems, for Putin to deal with the military shortfall is the ‘hidden’ mobilisation of those with the bare minimum of military experience. Yet this has already gone on since the start of the invasion. And this inflow is clearly insufficient for achieving strategic goals in Ukraine, for which, according to military analysts’ estimates, Russia would need at least 500,000 troops. Some of Putin’s recent attempts to shore up his army seem frankly desperate: the creation, for example, in many regions of ‘volunteer battalions’ of about 400 fighters each. This may add up to 15-25,000 soldiers – depending on how many Russian regions succeed in creating them. Yet given that in most the upper age-limit for soldiers has been increased to 50 and in some areas even to 60, the quality of these troops is open to question. Russia’s apparently unlimited human resources can thus only be used in a strictly limited way.

The Ukrainian army is also suffering heavy casualties, of course, though their manpower situation is quite different. In Ukraine, mobilisation was announced right after the invasion; as the Ukrainian defence minister told the Times in a recent interview, Ukraine is massing a million-strong fighting force to take back its southern territory, equipped with western weapons.

Much, indeed, now depends on these Western weapons. While Russia has been reduced to falling back on old stocks, Ukraine’s inflow of materiel is potentially limitless. Yet this is only true if – a big if – the West is really committed to seeing her win. Recently we saw how Ukraine, using Himars high-precision missile systems provided by the US, destroyed more than 20 major Russian ammunition depots and command posts that were until then too far behind the front lines for traditional artillery. By the end of July, Ukraine will still have only 12 HIMARS units. Though it’s causing considerable logistical problems to the Russians, scattering their reserves and hindering any meaningful attack, it’s still not enough to support an offensive. As defense minister Reznikov put it: ‘We need more HIMARS and we need them urgently’.

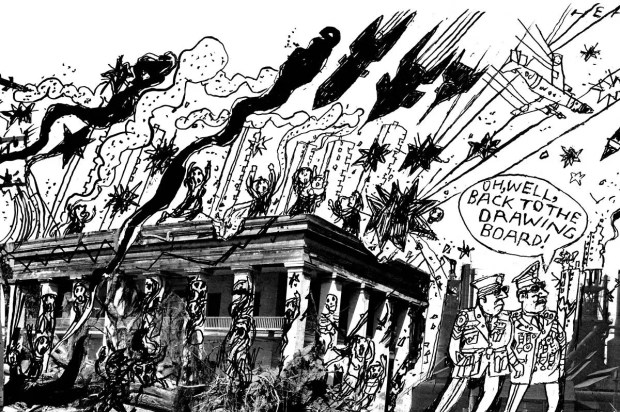

Will these actually arrive in the necessary quantities? While Ukrainian cities are being methodically destroyed in a rocket terror-campaign, it seems the West is committed simply to sustaining a stalemate. They are bringing to the front just enough ammo for the Ukrainians to hold out, but to do little more than that. There is a widespread assumption that the war in Ukraine is ‘existential’ for Putin – something he cannot lose. As Margarita Simonyan, one of Russia’s chief propagandists, told TV viewers back in April, nuclear conflict is ‘more probable’ than Russia accepting outright defeat. Behind the Western parsimony may lie the fear that Putin will resort to escalation (nuclear or otherwise) if the army is pushed back to Russia’s borders. At the same time, Russia has already failed and made its retreat in the north; it recently pulled out troops from the strategically important Snake Island, spinning it to the world as a gesture of Russian ‘good will’.

What prevents Russia, then, from accumulating enough ‘good will’ to give up the whole territory of Ukraine? There is no pretext too absurd these days to be foisted by a pliant Russian media on the public: that the goals of the ‘special military operation’ have been achieved, the ‘vicious attack’ on Russia foiled, and that it’s now going home time in the bloodlands of the Dnieper. The popularity of this war is not such that Putin need be over-concerned about the pro-war lobby. Should the flow of modern ammo from the West increase, he might be left with no other option but a climbdown, something he will definitely wish to avoid through ‘negotiations’. The Ukrainians may have been warned by Russian deputy minister of foreign affairs Andrey Rudenko to come to their senses and the negotiating table before Russian territorial gains get any greater. But ‘territorial reality’ is a fluid thing these days and can change in Ukraine’s favour too: there are credible plans afoot to retake Kherson, and in areas around the city Ukrainians are slowly but steadily pushing back.

With enough weaponry from the West and enough ‘good will’ from Moscow, the Ukrainians could win this war. Whether the Western powers-that-be actually want them to – that is another matter.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in