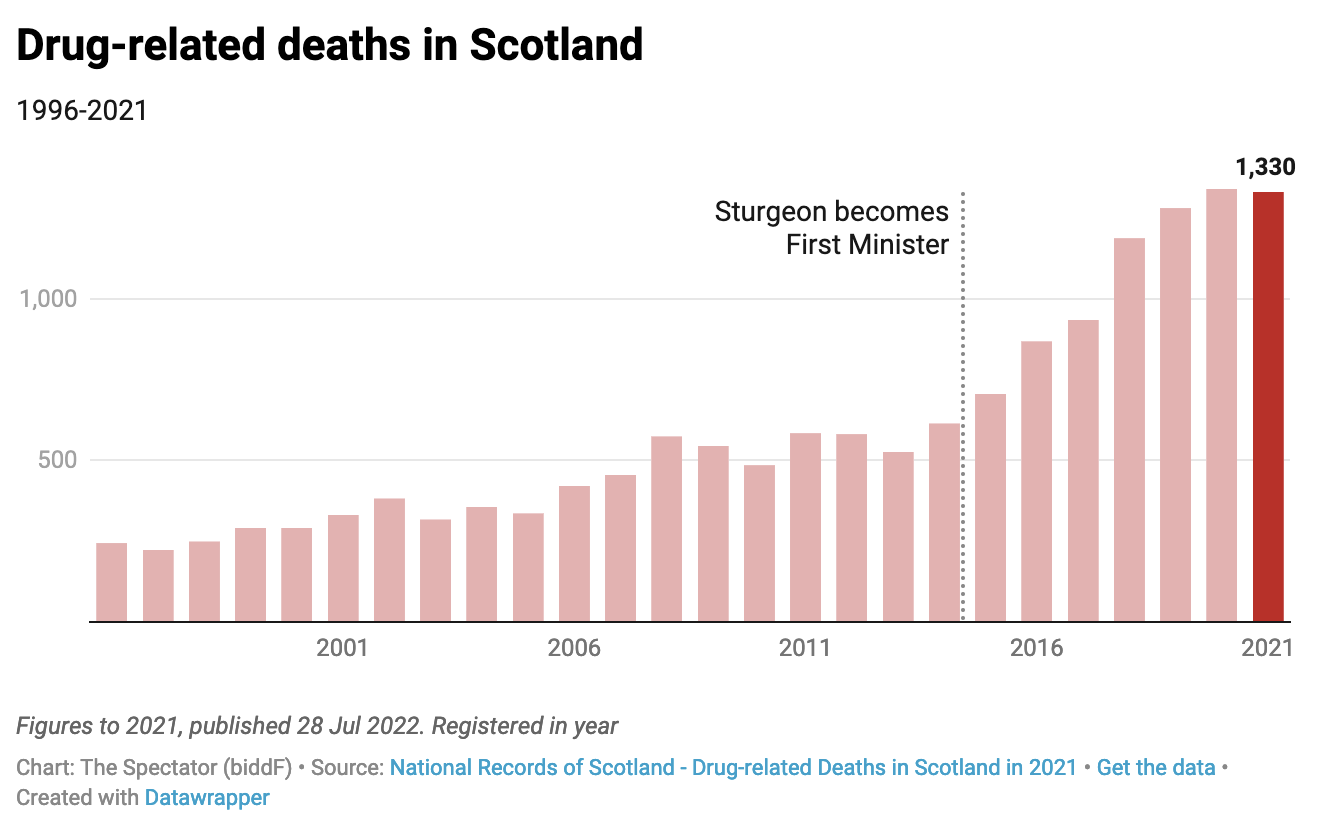

The Scottish government’s attempts to spin the latest drugs deaths statistics are a grim response to a total failure of public policy, not to mention revealing of the attitudes of those responsible. While admitting the ongoing problem was ‘unacceptable’, the Scottish government could be found ‘welcoming an end to seven annual increases in drugs deaths’ in the opening line of its press release.

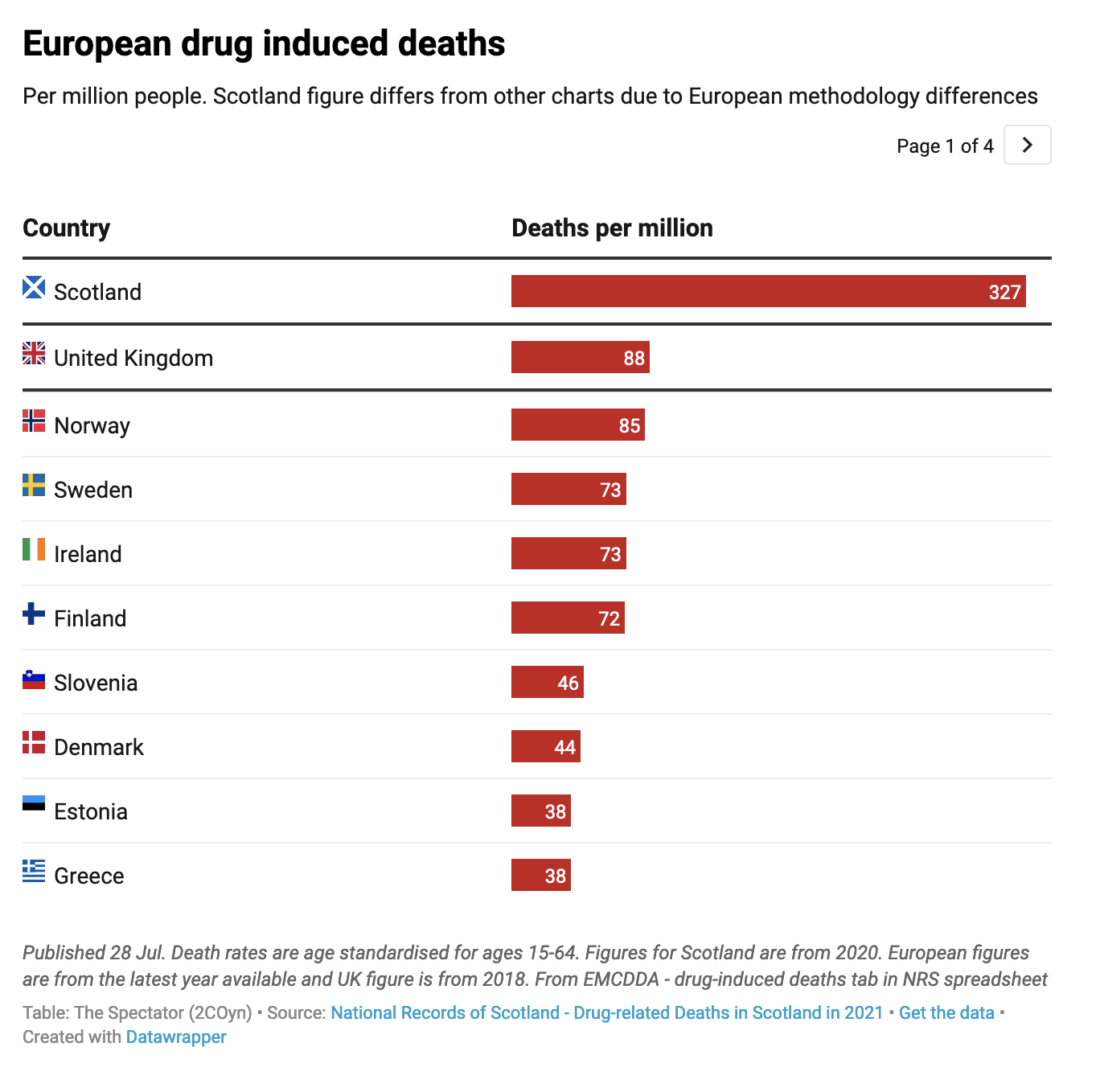

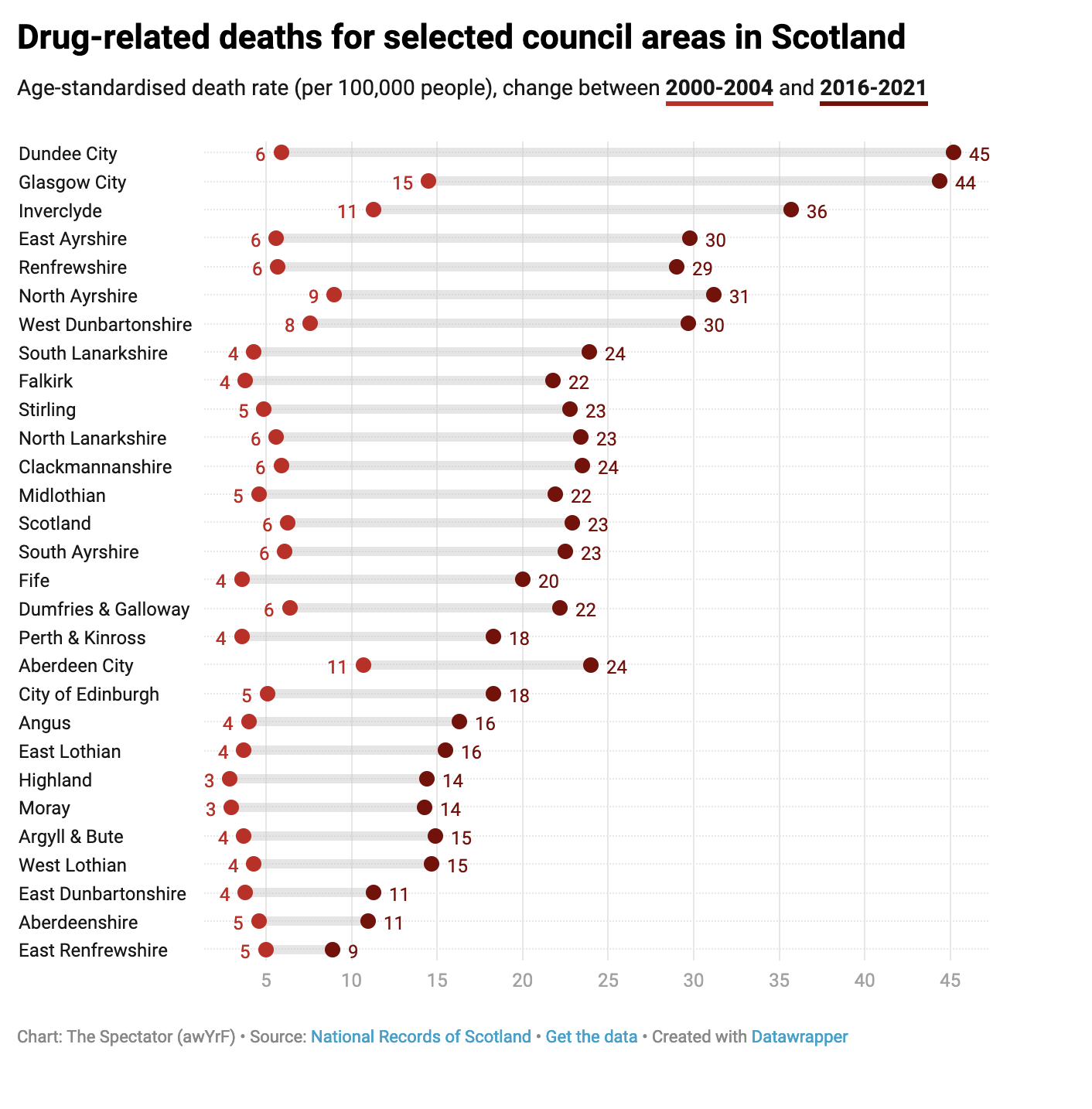

Last year, 1,330 people died as a result of drug misuse in Scotland, nine fewer than in 2020. It was the first time in seven years that the number of fatalities did not increase overall, but it also marked the second-highest annual death rate since records began. Deaths have increased among women, over 35s and residents of Glasgow, Tayside and Ayrshire. Scotland has significantly higher rates of drugs deaths by population than London, every region of England, Wales, Northern Ireland, the UK as a whole, and every country in Europe.

If that doesn’t drive home the scale of this epidemic, the raw totals are more than happy to oblige. Since the first full year of the SNP in government, 11,554 people have died from drug misuse. Since devolution began in 1999, the number is 14,736. For context of scale, that is twice the number of civilians killed so far by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, four times the death toll of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, and more than four times the number of Israelis killed by terrorism since 1948.

What we are seeing in Scotland is mass human sacrifice to a drugs policy that does not work. There are competing views about how best to address illegal drug use and dependency but the preservation of life should be a common starting ground. I have written previously about the Drugs Death Prevention (Scotland) Bill, legislation proposed by Labour MSP Paul Sweeney to set up overdose prevention centres (OPC). These facilities, which have proved successful in other countries, allow users to take drugs in a medically supervised environment with life-saving equipment on hand.

Sweeney, a former Royal Regiment of Scotland reservist, volunteered in an unofficial OPC in Glasgow and witnessed people being saved from overdoses, which is what prompted him to propose his bill. Despite the Misuse of Drugs Act being reserved to Westminster, Sweeney believes his bill is intra vires because it would not involve ‘producing’, ‘supplying’ or ‘offering to supply’ illegal substances, the key terms in the 1971 law. Responding to the new deaths figures, Sweeney said:

The time for talking has long passed. The solutions are no secret. We need action, and we need a coherent plan to address this crisis. It’s not good enough to write academic reports with recommendations that are never implemented – that helps no-one and it certainly doesn’t stop those at risk of dying an entirely preventable death.

He wants the Scottish government to ‘urgently’ roll out OPCs and scrap the SNP’s Drug Death Taskforce in favour of an independent body that can ‘scrutinise without fear or favour’.

Overdose prevention centres are not the only answer and not even the primary answer to Scotland’s drug problem, but they are a necessary first step. I am in favour of legalising drugs, something Sweeney’s bill emphatically does not do, but I would argue it is equally possible to favour the legal status quo and an abstinence-based approach to drug dependency while supporting OPCs as a preliminary measure to bring fatalities under control. Bluntly, you can’t get someone off drugs if they’re already on a mortuary slab.

If the Scottish government is serious about reducing drugs deaths, it is going to have to back Sweeney’s bill. For its part, the Home Office will either have to find a way to accommodate Scottish OPCs or put itself at the centre of a cross-border dispute about devolved powers and life-saving measures. A lot of people will have to decide whether their greater aversion is to medically-supervised drug-taking or the loss of human life on an unconscionable scale. Almost 15,000 dead in a quarter-century. How many more?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in