There’s a new Vice-Chancellor taking over at Oxford later this year. She’s Irene Tracey, warden of Merton College, and an expert on pain. Rather brilliantly, she wrote a Ladybird book about it, as well as specialist research, so she’s good at communication. More importantly, she’s an Oxford person all through, with only a postgraduate stint at the Harvard Medical School as a break from the university and the town. That sets her apart from the present Vice-Chancellor, Louise Richardson, whose specialist subject was terrorism and who didn’t have much to do with Oxford before she arrived in 2016.

Irene Tracey is, in fact, a welcome return to the old sort of Vice-Chancellor; a distinguished academic and college head. It would be good if she were also the kind of Vice-Chancellor who doesn’t see herself as the chief executive of some global corporate brand and with a salary that’s not actually insane. Louise Richardson’s £459,000 annual package (the going rate) – not to mention the squillions of air miles that go with the travel on the job – is nuts for a role which confers prestige on the possessor and isn’t justified by the sums brought into the university for projects which, to put it kindly, do next to nothing for its core functions.

Her arrival could be a chance for Oxford to right itself after over two decades of misgovernance, for there’s corrosion at the heart of the place. There’s not even any mystery about the reason for it. The central administration of the university has been expanding at the expense of its academic functions: teaching – especially tutoring and examining undergraduates – and research. The university’s central bureaucracy now accounts for 2,000 people – a huge size compared to 20 years ago, and arguably about twice as many as it needs for useful purposes.

Those problems began with the North reforms of 1997, under a hefty impetus from Whitehall, which changed the way the university was run, supposedly to make it more like a business, minus the crucial profit motive. It did away with two key units of democratic university government, the Hebdomadal Council and the General Board of the Faculties, which between them handled the administrative and academic affairs and were answerable to the University’s Assembly of Congregation. They were replaced with a single University Council with its own chair and an assortment of committees.

The university was divided into four subject-area divisions – each with a head who tried the maximise the administrative staff to equip this new layer of officialdom. As a disgruntled senior academic put it, the divisions ‘got into absurd levels of micromanagement. At one stage you couldn’t even invite candidates on a shortlist for an academic post for interview without prior divisional approval.’

As an exercise, it neatly summed up Parkinson’s Third and Fourth Laws: ‘Expansion means complexity, and complexity means decay’ and ‘the number of people in any working group tends to increase irrespective of the amount of work to be completed.’

Except that the university’s admin staff have made quite a lot of work for themselves in performance management and assessment of academics, which has the effect of distracting people from the actual job of teaching and examining students. They also reportedly interfere with academic procedures in crucial areas like undergraduate admissions and criteria for examining and assessing students, which has done its bit to contribute to the slide in academic standards. Most academic staff are now tied to the funding treadmill of research grants; they’re judged on their publications, not their brilliance as teachers, lecturers and examiners, which for undergraduate students is what matters. But it’s not the university that’s responsible for the culture whereby students getting into debt see themselves as customers entitled to a good degree in return.

One example of the busyness of the administrators is the University’s Strategic Plan 2018-23. It has all of 29 priorities. One of its commitments is to ‘encourage greater diversity in assessment’ in order ‘to reduce continuing gaps in attainment’ across the student population. So, if a dim candidate can’t get a good degree by sitting finals, then some other way must be found to do it.

There’s been a marked increase in appeals on the basis of mitigating circumstances, such as mental health issues and stress, in the last few years. During Covid, candidates were invited to make the most of ‘mitigating circumstances processes’. It’s just one element of grade inflation; most recently over 40 per cent of undergraduates sitting finals get a first class degree, and nearly all the rest 2:1. The General Board of the Faculties that the North reforms did away with was, among other things, the watchdog over academic standards. And the time between sitting exams and getting results is weeks shorter than it was 50 years ago, which can’t all be to do with IT.

Bureaucracy is expensive. And at Oxford it’s distorting the size and shape of the university. The average cost of a central administrator, including their office, is around £40,000 a year. The simplest way of funding them is by bringing in those useful revenue providers, overseas postgraduate students, on one or two year taught courses – with not much teaching. But you need about five of them to fund one central administrator. So, no surprises that in the last 20 years, their number has risen. (Oxford university declined to comment on this piece.)

Then there are the vanity building projects that the administration, with the Vice-Chancellor, enables and solicits from the rich, like the terrible new Parks/Reuben college, the Andrew Wiles Mathematics building (one thing maths doesn’t need is buildings), the grandiose Blavatnik school of government and the forthcoming Stephen Schwarzman Centre for the Humanities, which includes large scale exhibition and performance and teaching space for humanities subjects, something they don’t actually need – Oxford is already well provided. It’s all very American. If the hundreds of millions of pounds could have been channelled into scholarships, bursaries and university endowment, it could have been transformative.

Instead, the administration is squaring up for expansion: one new project, called (in the house style) Professional Services Together, declares, ‘we want to build on the great achievement of Oxford departments, divisions and services to shape a culture where we can provide professional services together and support our University’s core mission of education and research as one community’. What?

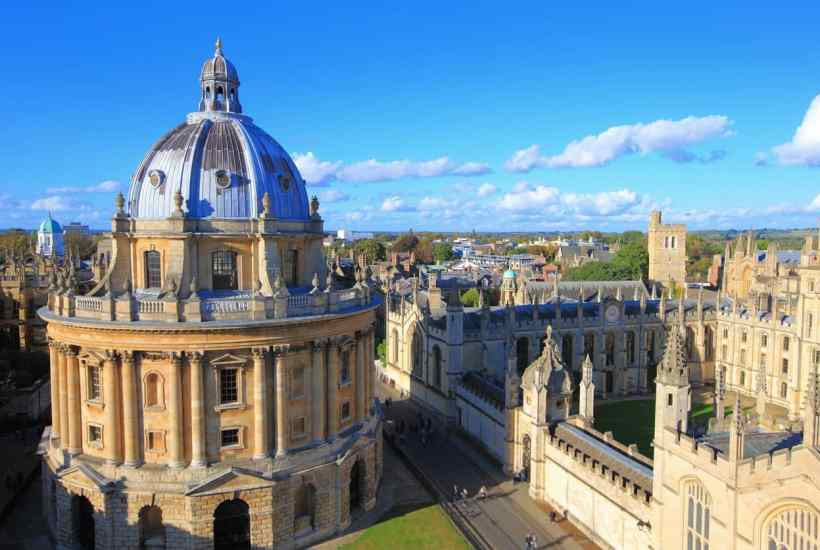

Oxford’s strengths – like Cambridge’s – are self evident. The colleges, besides having their own unique historic identity, are examples of the inter-disciplinary collaboration that’s currently terrifically in vogue. The colleges provide the tutorial system, which still allows for teaching by one tutor with one or two students at a time which is uniquely valuable. And it once had a reasonably democratic and economical governance structure. The first two need protecting; the third needs restoring.

The new Vice-Chancellor could put things right – she can do away with the stupid academic divisions (except perhaps for clinical medicine); restore the old system of policymaking by consensus; abandon vanity building projects and impose a budget on the central university administration to reduce its size. And if she could steel herself to take a pay cut of, say half, in her own pay, it’d do an awful lot to restore the reputation of vice chancellors.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in