Until very recently, political assassination was a mercifully uncommon occurrence in British politics, though that has changed. Previously when such murders did happen, they were usually associated with Ireland: the 1882 Phoenix Park murders of Lord Frederick Cavendish and Thomas Burke, the killings of Airey Neave and Lord Mountbatten, and numerous unsuccessful plots and near misses. One spectacular example occurred in June 1922, when Field-Marshal Sir Henry Wilson was shot dead outside his Mayfair house by two IRA operatives called Reginald Dunne and Joseph O’Sullivan, who were swiftly captured and hanged, after a trial whose procedures were sharply criticised by George Bernard Shaw among others.

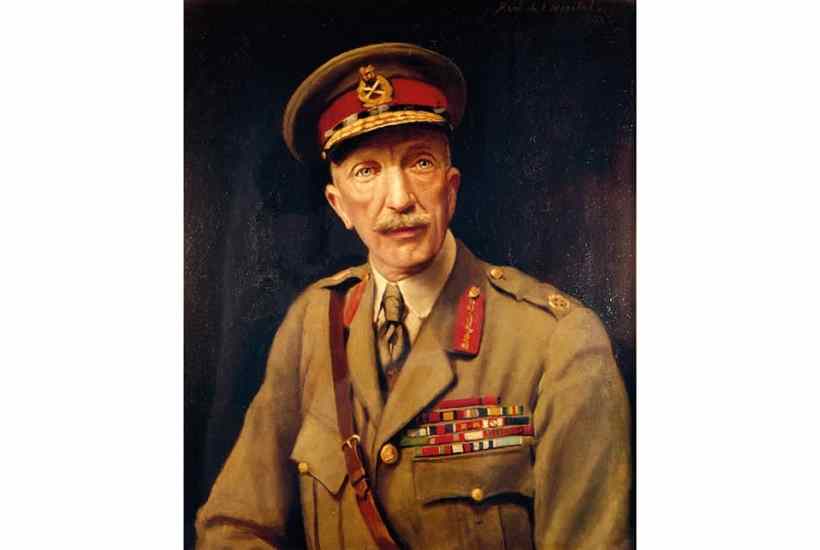

Wilson is not much remembered now, despite a fine 2006 biography by Keith Jeffery, but he was famous and controversial in his day. From a minor Irish gentry family in County Longford, he became a key figure in the first world war, and up to a few months before his death was chief of the imperial general staff. Rather than the sort of buffoon brilliantly lampooned in Joan Littlewood’s Oh, What A Lovely War!, in military terms he was modernising, intelligent, often prophetic and superbly tactless; his posthumous reputation was torpedoed by the publication of extracts from his savagely indiscreet diaries. Responsible for the British Expeditionary Force, he built close relationships with his French counterparts, notably Marshal Foch. But his opinionated outbursts alienated many colleagues and most politicians, whom he found universally ‘contemptible’. The ultimate Establishment fixer, Lord Esher, thought Wilson’s

Irish blood, exuberant with combative malice, in an unfortunate moment seduced him from the arid paths of military science. He plunged with delight into an Irish quarrel, which earned him from politicians the appellation of a ‘pestilential fellow’ and was destined to cripple his chances of obtaining the highest staff appointment in a war which he had correctly anticipated… For this he had himself and his Irish ancestors to blame.

Wilson was certainly seen as quintessentially Irish, and played up to it, but it was a very particular kind of Irishness – obsessively devoted to Union and Empire, and utterly dismissive even of limited claims to Home Rule, let alone the republican nationalism in the ascendant since the 1916 Rising. At the time of his death he was an MP for a Northern Irish constituency. This, and the part he had played during the ‘Curragh Mutiny’ in 1914 (encouraging Irish-based officers to resign their commissions rather than impose the Home Rule Act on Ulster), gave him the reputation of an Orange diehard.

In fact he was not a religious bigot, disapproved of sectarian violence and mercenary forces such as the Black and Tans, and did not – as was claimed – found the Ulster Special Constabulary, though he was military adviser to the new statelet. His death came at a very sensitive moment. Following a truce agreed in July 1921, the Anglo-Irish Treaty had been adopted by a narrow margin in Ireland, setting up the Irish Free State, to Wilson’s fury. Ireland teetered on the brink of civil war, which was precipitated by Wilson’s death, after which the British government pressurised the new Irish government to proceed against the rebels.

Ronan McGreevy is not the first person to devote a book to Wilson’s assassination, but he is the first to delve deeply into the background and motivation of the assassins –using much new evidence from Irish sources such as recently available witness statements from the Bureau of Military History, and from applicants for military pensions. He draws a rich and nuanced picture of Dunne’s and O’Sullivan’s backgrounds, placing them not only in the world of Irish London but against the background of post-war trauma (they were both British Army veterans, O’Sullivan having lost a leg at Passchendaele). Above all, McGreevy establishes a network of IRA plans and operations against British public figures, studying potential targets ‘like film stars’. Dunne played a senior role in such reconnoitres, stretching back to before the Truce. McGreevy also uses family documents to build up an arresting picture of a devout Catholic, proudly celibate, solaced in imprisonment by his deep love of classical music.

Above all the question arises of who planned and authorised the murder. Jeffery concluded the killers were – as they claimed – acting on their own initiative, believing Wilson the author of anti-Catholic ‘pogroms’ in Northern Ireland. Others have claimed that the IRA supremo Michael Collins ordered the assassination before the Truce, and that the order remained unintentionally ‘live’. McGreevy convincingly argues against this from Dunne’s and O’Sullivan’s records, ancillary evidence (notably from a ‘third man’ who dropped out of the picture, Denis Kelleher) and IRA command structures. He believes that Collins indeed authorised the operation, and did so shortly before the event – despite having signed the Treaty and formally renounced hostilities against British targets. This would fit with recent research on Collins’s authorising actions in Northern Ireland as well as making sense of Dunne’s and O’Sullivan’s attitudes and actions before and after firing those shots in Eaton Place. They seemed utterly convinced that they had been serving the cause of Irish nationalism as rationalised by the orders of the Republican movement.

Arguments will continue, but McGreevy has certainly moved them on a decisive stage. Above all his book draws a vivid picture of the many varieties of Irishness stirring in the violent cauldron of events exactly a century ago, reflecting emigrant cultures, British Army service at contrasting levels, and the inherited antipathies invoked by his title – which did not dissipate. ‘All three men died for countries they were neither born nor raised in.’ Dunne’s parents (who had known nothing of their son’s political involvements) moved to Ireland to live an unhappy life, while in retaliation for Dunne’s and O’Sullivan’s executions, the modest Wilson ancestral home in Longford was burned out and the family left for England. Blinkered though Lord Esher was, perhaps he was not far wrong when he felt that, in the Wilson tragedy, Irish ancestry had something to answer for.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in